Photographer and Alaska native Acacia Johnson first visited Antarctica in 2010 as a tourist. From then on, working there became a passion: she was fascinated to see how the ice there was changing, and to experience the feeling of traveling back in time to an era untouched by humans. “The scale of human presence on earth — infinitely small, is felt in Antarctica. There’s a reason why this entire continent is devoted to science and peace,” she notes.

When previously working on expeditions, Johnson had often been one of the only women on a team. That was different in Antarctica, where women made up at least half of her team of logistics coordinators, guides and scientists. But this was not always the case. For years, Antarctica was a hostile place for women, and they faced significant political and social obstacles if they wanted to go.

In 1914, when British explorer Ernest Shackleton was recruiting for an expedition to Antarctica, he got letters from “three sporty girls” applying to join. “There are no vacancies for the opposite sex on this expedition,” he responded. As many researchers have noted, Antarctica was then — and still remains — a masculine realm in popular imagination: never permanently inhabited, beautiful but hostile. Men were celebrated for testing their character by claiming and administering this new territory. Images of men fighting blizzards fed into the mythology of the conquering hero. Expedition writing from the early 20th century refers to Antarctica as an “aloof, virginal woman to be won through chivalrous deeds.”

In the 1960s, geologist Janet Thomson recalled the reply one female colleague received to her expedition application, which stated that there were “no facilities for women” in Antarctica, including no shops and no hairdresser. Women were even banned from the U.S. Antarctic Research Program until 1969.

Though women’s opportunities to join expeditions have been extremely restricted, women have nevertheless fought to play a part in the region’s history. Maori oral tradition even suggests women traveled in Antarctic waters as far back as 650 AD. In 1935, Caroline Mikkelsen became the first woman in recorded history to set foot on one of Antarctica’s islands.

Since then, the polar gender dynamic has continued to shift, with more and more women taking roles as base commanders, expedition leaders, heavy equipment operators, scientists and researchers.

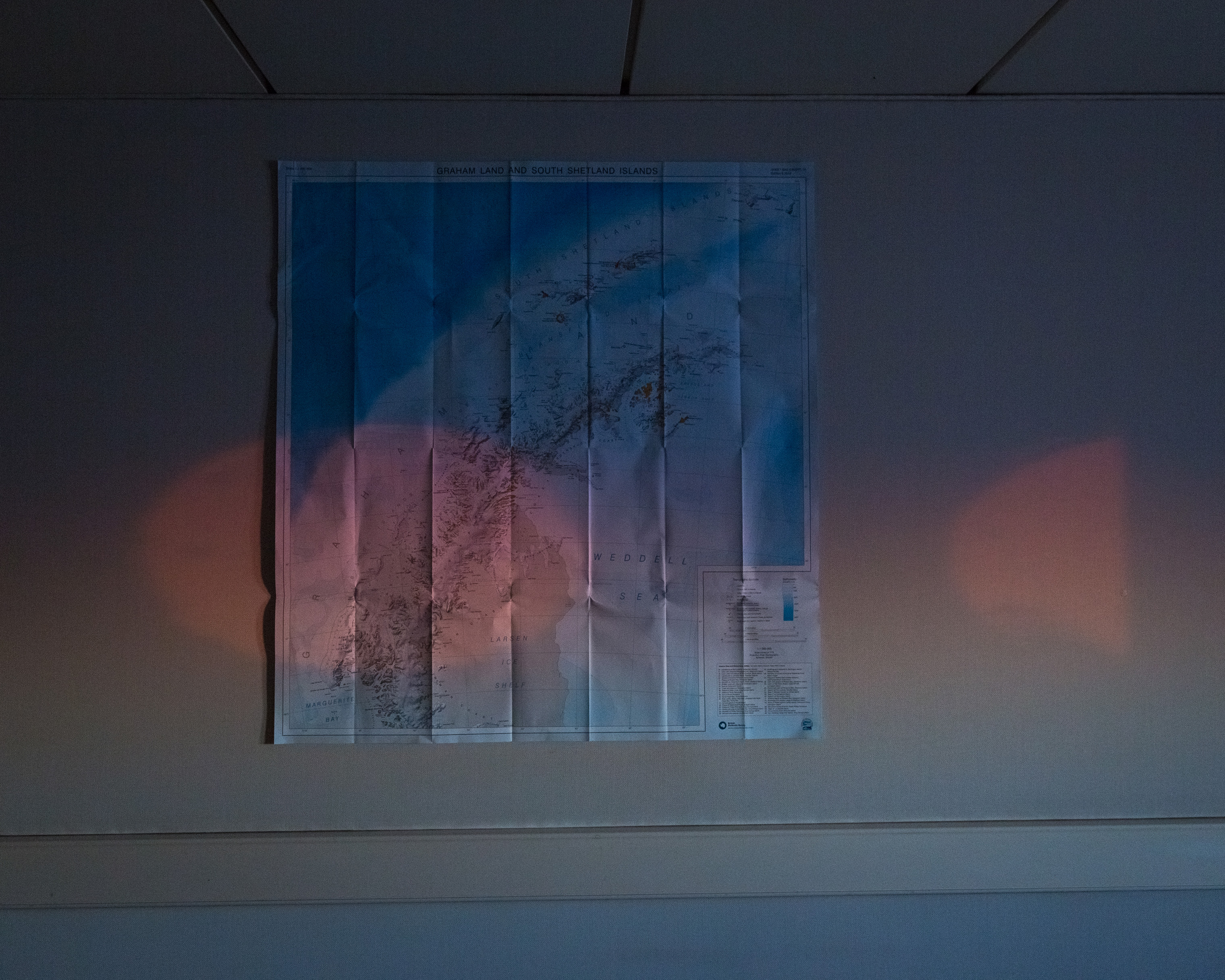

Johnson introduces us to some of those working on the continent today in her series ‘Women in Antarctica.’ In the 32 expeditions to Antarctica she has made as a guide, Johnson says she has been able to work alongside extraordinary women at 10 international research stations. She told TIME that “breaking down gender stereotypes is an ongoing process, in Antarctica as everywhere else, but we’re making good progress, and it’s inspiring to be a part of. We’ve come a long way — women are now overtaking men in some areas, which is incredible — but that doesn’t mean we should lose sight of how far we still have to go regarding diversity.”

“What I’ve realized all over the years is that a lot of women don’t realize they can do things; go on expeditions; take leadership roles or work in extreme environments. It’s not even in their subconscious. A lot of people don’t even consider guiding in the Polar Regions an option as a woman – and leading is a whole other story. You imagine Shackleton or Scott or Franklin. We keep hearing their names again and again. And we don’t even hear about the women.”

“I often think about the strategy you would need in an emergency. Courage, confidence, and caring. Especially caring. Guiding is a working environment, working inside a sort of family. To lift each other’s spirits, we don’t need strong muscles. We need a strong mind. And anyone can have a strong mind.”

“I love being a woman working in a man’s world. It challenges [men], but I think it also brings humor, delight and a nice balance to working in such an extreme environment, especially for extended amounts of time. For me, as a woman, the secret is not to compete or try to prove to the men how equal I am, but more to accept our differences and unique strengths and form a unified team who has each other’s backs.”

Culturally sometimes you’ll get people just not understanding seeing women in these scenarios. Like “what are you doing here, you’re too pretty, you should be in an office” or “is your family okay with you doing this?” I rarely say what I want to say, which is: “do you ask the male expedition guides this question?” I already know the answer. They don’t.”

“Antarctica is beyond my imagination. It’s a place for everything, but at this moment for me, it’s a place where I look for myself.”

“If people seem surprised [that I’m a Polar historian], I just laugh and say, oh, I tried to grow a beard and some white hair, but couldn’t quite manage,” she says. “It makes them realize that that’s what they were expecting.”

Today, the landscape is changing. Efforts like the Homeward Bound expedition (a leadership initiative and the largest-ever female expedition to Antarctica launched in 2015), and a global “Wikibomb” to celebrate the notable contributions female scientists have made to Antarctic research, are broadening the narrative and raising the visibility of female scientists and explorers. Johnson plans to continue this series, with a greater emphasis on women who work on research bases and in science. “Through images, I want to show the Antarctica that I know— a seasonal home to a growing community of inspiring women, drawn together by this captivating place. I wanted to create portraits that challenge conventional ideas about who works in Antarctica, and how, and why.” she told TIME.

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision