When people envision the South, they may conjure images made by photographers who stylized the “Southernization” of aesthetics during the last century. Walker Evans, Gordon Parks, Sally Mann and William Christenberry. There are the pastoral landscapes covered in Spanish moss; the storybook scenes of small towns and people whose lives have only known those small towns; historical images of segregation and stereotypical images impoverished Americans in crumbling homes. These images have had a lasting impact, but at a cost.

“The perception of the South in photography is 50 years behind the reality,” says Richard McCabe, curator of photography at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans. “It’s a place that’s shrouded in mystery and mythology and legend.”

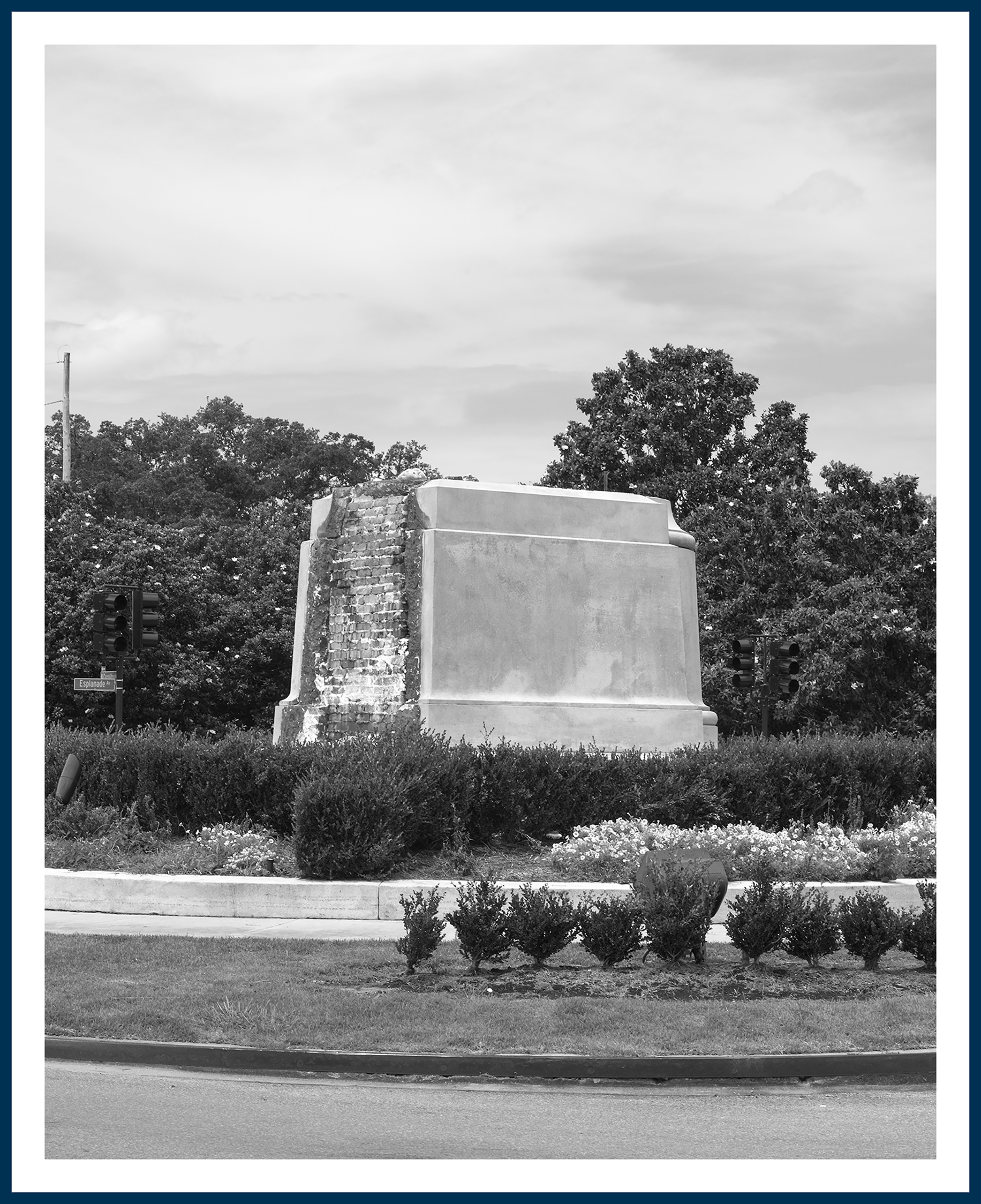

TIME recently devoted a special issue to the changing South, with photographers who reflected a variety of voices that either showed us the familiar in a surprising way, or a subject matter that we had not seen before. Their work, and more, is included in two upcoming exhibitions: New Southern Photography (opening Oct. 6) at the Ogden, and Southbound: Photographs of and about the New South (opening Oct. 19) at the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art at the College of Charleston. Both exhibitions explore the sense of time, place and identity of a region in flux.

The show at the Ogden, curated by McCabe, features the work of 25 emerging, mid-career and established photographers. It explores the role of photography “in formulating the visual iconography of the modern New South.” The photographers probe regional identity, memory, deep familial connections to the land and tension between past and present.

The exhibition at the Halsey, co-curated by Mark Sloan, its director and chief curator, and Mark Long, a professor of political science, features 56 photographers who have captured the region since the turn of the century. Its purpose, according to the museum, “is to investigate senses of place in the South that congeal, however fleetingly, in the spaces between the photographers’ looking, their images, and our own preexisting ideas about the region.”

As the two upcoming photography exhibitions make clear, the contemporary work being made in the South today works to break free of standards and stereotypes. The collective work illustrates the region’s evolving demographic and geographic identity, widening our understanding of what the South is and can be.

“One of the significant events taking place in the South today, as it grows and converts from being rural landscape to being suburban and urban landscaped, is the tension between the way the land has been for hundreds of years and what’s happening on the outskirts of Orlandos and Atlantas and Charlottes,” Alan Rothschild, founder of the Do Good Fund, an organization developing a permanent collection of Southern photography since World War II, tells TIME.

“People are playing with traditional genres — landscape, portraiture and still-life. What’s happening, especially in the landscape, it’s a post-modernist take on the landscape, people manipulating the image — reimagining of the imagery in the studio, applying paint onto the surface,” McCabe tells TIME. He points to the work of John Chiara, whose photographs of the Mississippi landscape, made through a large pinhole camera on the back of a trunk, become painterly, abstract and highbred-like images.

Rothschild points to the work of Atlanta-based photographer Peyton Fulford as an example of successful chronicling of communities that historically have not received much attention. Fulford’s project “Infinite Tenderness” focuses on intimacy and identity among queer youth who grew up in small towns and rural areas. McCabe cites the work of Tommy Kha, a queer, Asian-American photographer from Memphis, whose work focuses on his personal identity through self-portraiture.

Another photographer, RaMell Ross, who is based in Alabama and Rhode Island, has been photographing and filmmaking in Hale County, Ala., for seven years. In McCabe’s words, it “is the most, probably, iconic county in Southern art and Southern photography.” Ross, who TIME commissioned for a portfolio of film sets in Georgia, or “Hollywood South,” is exploring Hale County to uncover elements left out by Christenberry and Evans, who largely focused on the white communities.

“The African American community is largely invisible in the early work of Evans in Hale County,” Long tells TIME. As McCabe tells it, there is a significance to an African-American returning to Hale County and taking control of the narrative. “It shines a light on communities that were previously invisible.”

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision