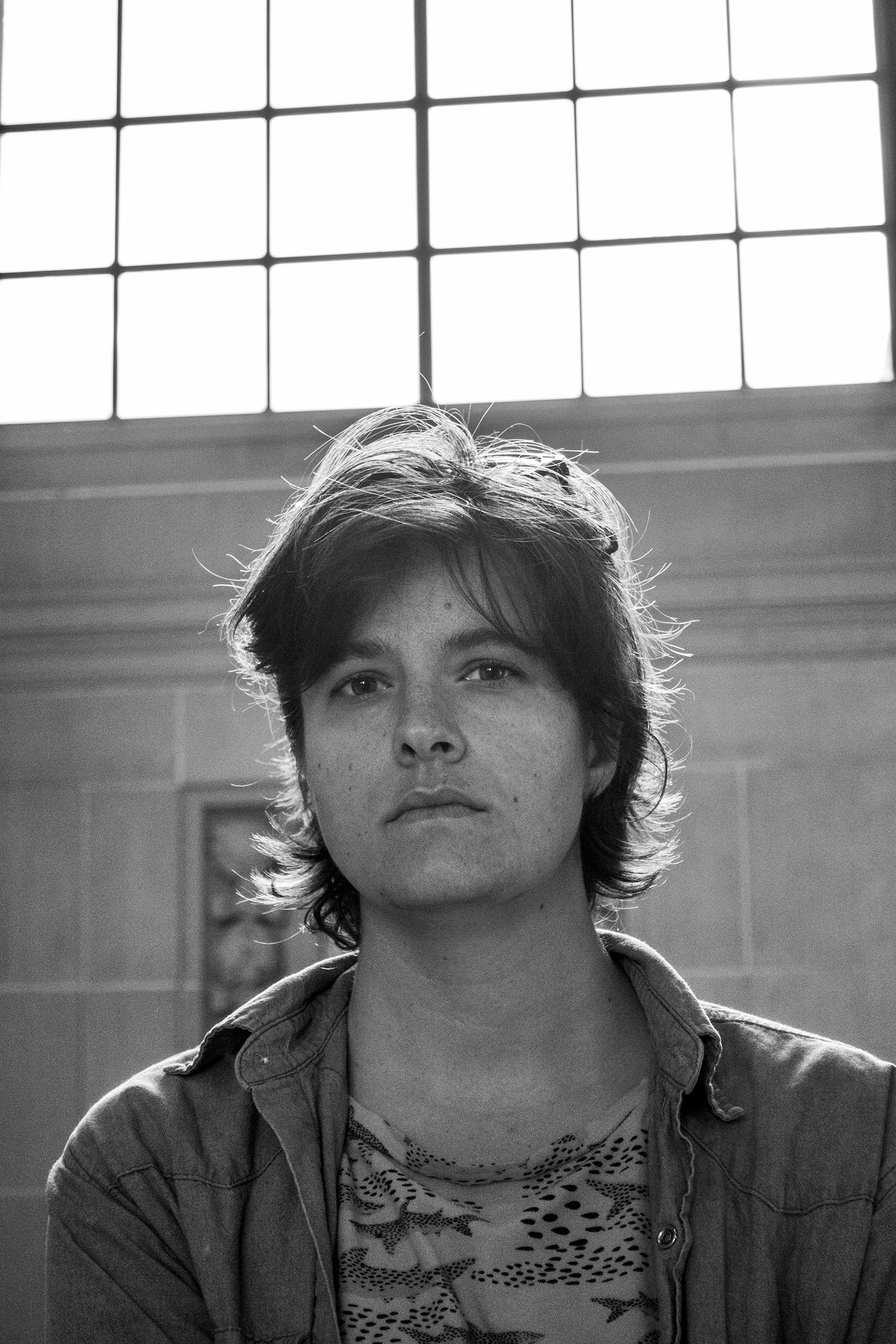

Rachael Pacella had been doing better. No longer did any little sound—the buzz of a cell phone, a door opening—cause her, to twitch. She wasn’t freezing in crosswalks.

The therapy and medication helped. So did a pottery class. Anything to take her mind off that day.

Then Pacella retraumatized herself. In February, she testified before a state legislative committee in support of a bill that would regulate rifles and shotguns. It was an unusual situation for an environment reporter, but then Pacella works for the Capital newspaper of Annapolis, Md. She related how on June 28, 2018, she was in the newspaper’s office, heard a pop and saw a glass door shatter. How she crouched under her desk. How she made a run for it, but slipped and slammed her face into a door. The shooter had barricaded that exit, so Pacella, 28, hid between two filing cabinets. She tried to control her heavy breathing. She hoped the shooter wouldn’t notice the blood from her forehead, streaked on a partition above her hiding spot. The shots were getting closer. Pacella whimpered. Dear God, she thought. What if he heard me? She clamped her hand over her mouth.

Pacella told the lawmakers how everything fell silent until the police escorted her, and colleagues who had also survived, out of the building and into a life that will never be the same. “They instructed us to keep our eyes forward,” she said, “and step over Wendi’s body.”

Journalists, as a species, generally despise being the subjects of the news. We sign up to see our names in the bylines, not the headlines. But events put the staff of the Capital Gazette in a new place. As journalists, they were a new addition to the expanding annals of American gun violence—uniquely positioned to register all its impacts, from the initial moments so horrifying they draw the attention of the entire world, through the far longer period when that attention has moved on, and they don’t get to.

“There are people all around the country and all around the world who are just sitting with these massive amounts of PTSD, and we need to know how to get through it,” says Capital Gazette reporter Selene San Felice, 24, who hid under a desk to survive the rampage. “We’re having a national conversation about mental health and anxiety, but we’ve got to do something to talk about what happens after.”

The shooter that Thursday afternoon was a man named Jarrod Ramos, nurser of a years-long grudge against the Capital because of a 2011 column about his guilty plea for harassing a former high school classmate. After blasting his way into the newsroom, he fatally shot five people: Wendi Winters, the features writer who charged at Ramos with a trash can and recycling bin; editorial writer Gerald Fischman; deputy editor Rob Hiaasen; longtime sportswriter John McNamara; and sales assistant Rebecca Smith. Pacella was one of the six people in the newsroom as it happened who survived the shooting.

On Oct. 28, Ramos admitted to the killings in an Annapolis court. But he has also pleaded that he’s not criminally responsible for his actions, Maryland’s version of the insanity defense. A trial will determine whether he’ll be sentenced to a state prison or to a maximum-security psychiatric hospital.

TIME has spent the past year chronicling the aftermath of the Capital Gazette shooting. We’ve trailed editors and reporters on the job and in their homes. The staff was featured in our 2018 Person of the Year package on journalists who serve as “The Guardians” of truth while their work is under attack around the world. A new TIME Studios film, directed by photojournalist Moises Saman, provides an intimate look at how staffers continued to soldier on after witnessing tragedy in their workplace and losing beloved colleagues and friends. The Capital covered its own trauma, putting out the next morning’s paper written and edited by grieving staffers on the day of the murders. The work earned the Capital Gazette a special citation from the Pulitzer Prize board in April.

While coping with post-traumatic stress—not to mention the economic pressures that have gutted vital local journalism outlets around America—reporters like Pacella continued to pound their beats, covering the zoning meetings and spelling bees that form the fabric of any American community. When it is scheduled, they will also cover Ramos’ trial. “This person obviously wanted to silence us,” says Capital assistant editor Chase Cook, lead writer on the deadline story about the murders. “That’s never going to happen.

The Capital has emerged a symbol: of press freedom, of the vitality of community journalism, of the fight against gun violence. “People have interpreted us,” says Capital editor Rick Hutzell, “how they see fit.”

There is a pattern after mass shootings, which Pacella’s statehouse testimony fit in only too well: a moving plea for change from a mass-shooting survivor, followed by … no real change. The gun-regulation bill stalled. Meanwhile, shootings elsewhere made headlines: Virginia Beach; El Paso, Texas; Dayton, Ohio. None of it damped the resolve of the newsroom. The staff has promised itself that what happened to the Capital won’t be in vain.

“With each [mass shooting], we all become a little number. Our souls are a little deader. What it means to be American is a little cheaper, a little less valuable,” says Hutzell. “That’s why it’s up to us as journalists to figure out a way to make it matter for readers … That’s our job. And if it’s hard because we are becoming numb to mass violence, too bad. Figure it out.”

Photographer Joshua McKerrow wasn’t in the newsroom that Thursday. But his survivor’s guilt is still intense. McKerrow arrived at the nearby U.S. Naval Academy 15 minutes before sunrise on June 28, 2018, for one of his favorite assignments: snapping pictures of induction day for incoming plebes. Afterward, instead of returning to the office, he made what was likely a lifesaving decision: he drove toward Baltimore to pick up his daughter. He planned to take her out for her birthday.

Then he spotted a call from Hutzell, the boss, on his cell phone. Never good. “It means something really bad happened that you have to go cover,” he says, “or you f-cked something up.”

The news proved worse than McKerrow could ever imagine: Hutzell said he’d heard about a shooting at the newsroom. McKerrow turned his car around and started driving toward the office. “I felt like I was kind of just leaving the vestiges of myself behind,” he says.

Through the afternoon and into the evening, McKerrow toiled at the scene of the crime, gathering photos of his deceased friends from the Capital’s archives for the next day’s edition. He says that working on the story worsened his trauma but that he had no choice—there was a kind of imperative. “I knew as soon as I turned my car around that this was going to be sticking my hand into a fire,” McKerrow says. “And if you ask me whether it was worth it, it was absolutely worth it. As hard as it is to live with myself now, I don’t know if I could have lived with myself at all if I’d done the wrong thing.”

McKerrow opens up about his post-traumatic stress to emphasize that these shootings leave so many in their wake. Survivors need to seek help. He’s still seeing a therapist. He’s had suicidal thoughts. “I don’t get the joy from a cup of coffee that I used to,” says McKerrow. “You don’t get the joy from anything you taste, frankly. I’ve had moments in the past year with my kids and we’re playing in the leaves and there’s shrieking of joy and laughter, and I’m thinking about the shooting and there’s a part of me going, What the f-ck? This is what you’re alive for, to experience these moments. Why are you not experiencing this? Why aren’t you feeling the joy of this that you should? You’re alive. You survived.

“I’d like the coffee to taste the way it used to taste.”

Capital Gazette staffers have learned all too many lessons about grief. When people check in on him, McKerrow often doesn’t respond. Then people get mad at him. There’s a reason, however, for his silence. Lying—by telling people he’s O.K.—saps his energy. But he doesn’t want to pass on his pain to others. “If you know someone going through trauma, you can help them by reaching out but letting them know it’s O.K. if they don’t reach back,” McKerrow advises. “They don’t know how to talk to you. They don’t know how to love you the way they did. They don’t know how to laugh with you the way they did.”

For some, antidepressants have helped. So has the free therapy offered by Tribune Publishing and Baltimore Sun Media, owners of the Capital, and local mental-health providers. Hutzell is flexible with time off. The journalists are quick to point out their good fortune, and wish others similarly impacted by these incidents received comparable support. “I’m the most privileged shooting survivor in this state,” Pacella says.

Staffers also turned to all sorts of distractions. Danielle Ohl, an investigative reporter, cooks. McKerrow has taken up production design for the Annapolis Shakespeare Company. San Felice took Wendi Winters’ ashes to Istanbul, where the late journalist grew up. Winters’ son spread them in a park there.

Pacella found pottery. Her projects can take weeks to complete, which gives her goals, something to look forward to. In the weeks after the shootings, Pacella carried a notebook wherever she went, writing down observations, sketching the buildings and trees that she was seeing. The habit gave her a sense of power and control.

After her testimony, Pacella took a few days off to recover. Her healing, while by no means complete, is progressing. Like McKerrow, she reported from the Naval Academy induction the morning of the shooting: unlike McKerrow, she returned to the office right after. But in June, Pacella went back to the Naval Academy for this year’s induction. Her piece ran in the newspaper on the one-year commemoration of the shooting. Returning to the Scene of an Oath Interrupted, read the headline. The process offered some sense of closure.

“There is also an element of just being like, well, look at me,” says Pacella. “Look what I’m still doing.”

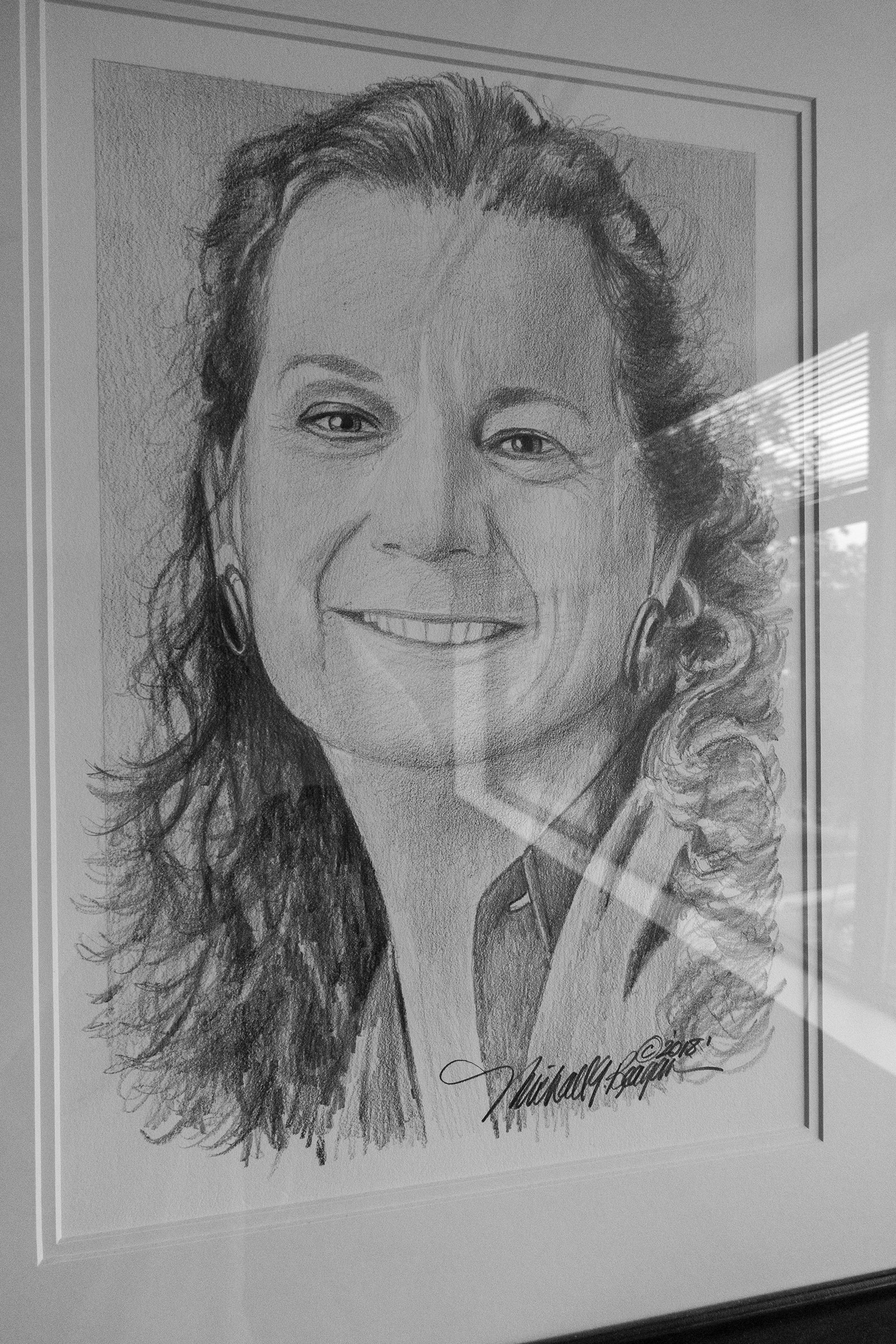

Photographer Paul Gillespie, a fellow survivor, poured his energy into creating portraits of Capital staffers and family members of the five employees who died. His exhibit, “Journalists Matter: Faces of the Capital Gazette,” launched at an Annapolis art studio in early October. “These missing people are holes in our humanity,” Andrea Chamblee, the widow of John McNamara, said at the opening. The occasion, somber as it was at one level, gave the extended Capital Gazette family a rare chance to gather and smile over a few drinks. In her portrait, Chamblee, who also testified before the Maryland General Assembly in support of tighter gun laws, clutched one of McNamara’s press passes.

“For so many weeks and months, I really wanted to hold up a mirror to myself to see if that would give me a clue as to what was happening inside me,” she says, through tears. “And when I look at the picture, I see clues that I was looking for. I see anguish and bewilderment and love that I felt for my husband. And focus, vicious focus, on what I have to do now.”

In her photo, San Felice stares straight into Gillespie’s camera. With a slight, empowered smile, she holds out a notebook and pen. “I don’t want every picture of me to be the sad picture of the night of the vigil, or me hugging someone at someone’s funeral,” says San Felice. “I want to wear a f-cking cape. I want to go to the Pulitzers, and I want people to know that I’m worth something. I’m more than this.”

After the shooting, the Capital Gazette did not return to its old offices. The paper set up shop at a temporary home, sharing space with the University of Maryland’s Capital News Service before moving to a new space in early June. There, the first pot of office coffee felt like a minor triumph, a small but important part of moving on.

The legal process, on the other hand, still carries elements of trepidation. Hutzell hired a new reporter to cover Ramos’ trial. He’s setting him up in a conference room, away from the other staff, so the reporter can ask questions without risking upsetting his colleagues.

And while Ramos’ guilty plea has likely spared the newsroom from hearing the most gruesome details of the killings or seeing footage of the rampage in court, the trial focused on the murderer’s mental state will still

be difficult.

“After the shooting, I set three milestones,” says Hutzell. “Keep the paper going. Get us into a new office. And get through the trial.

“Two down.”

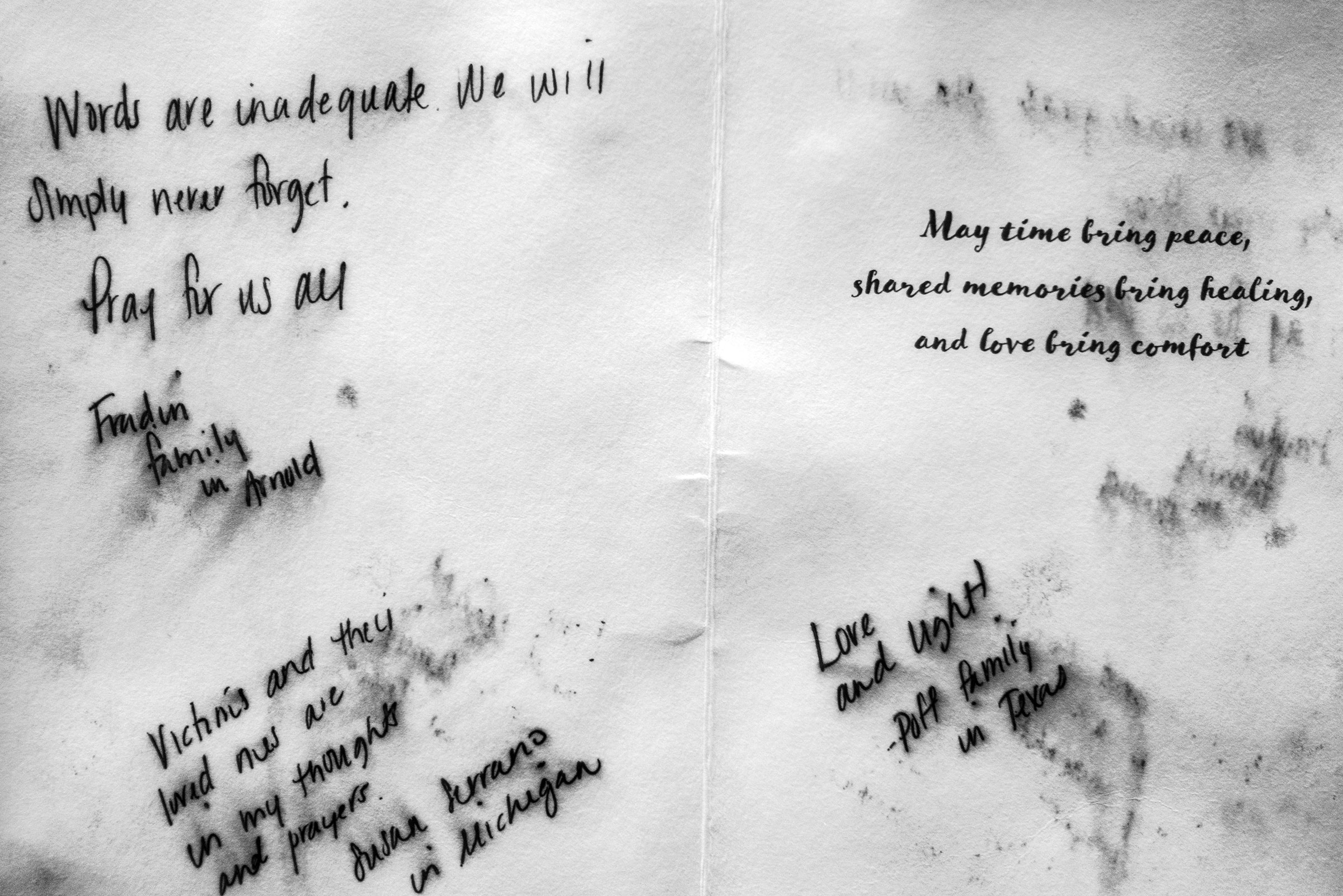

Capital journalists are attempting to embrace the good things. The world—particularly the Annapolis community—continues to show an outpouring of love. New opportunities, small solace that they are, have arisen from the tragedy. The Pulitzer Prize board awarded the Capital a $100,000 grant; the extra money enabled, for example, San Felice to take on in-depth, high-impact projects. The Capital has partnered with the nonprofit ProPublica, a leading investigative newsroom, to examine public housing in Annapolis.

“Putting out the paper has value besides what’s in the paper,” Hutzell says in a room in the Capital’s new space. “Every day you’re here is another day farther away from what happened. Every day you’re here is another day when you’re alive. And we have friends who are not. Every day here is another day we can honor their memories, and do the work we love.” —With reporting by Paul Moakley/Annapolis

Moises Saman is a photographer and director based in New York.

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision