<!-- wp:gutenberg-custom-blocks/featured-media {"id":3657747,"url":"https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/iphone-social-apps-instagram.jpg","caption":"","credit":"Elizabeth Renstrom for TIME"} -->

<!-- /wp:gutenberg-custom-blocks/featured-media --><!-- wp:paragraph -->

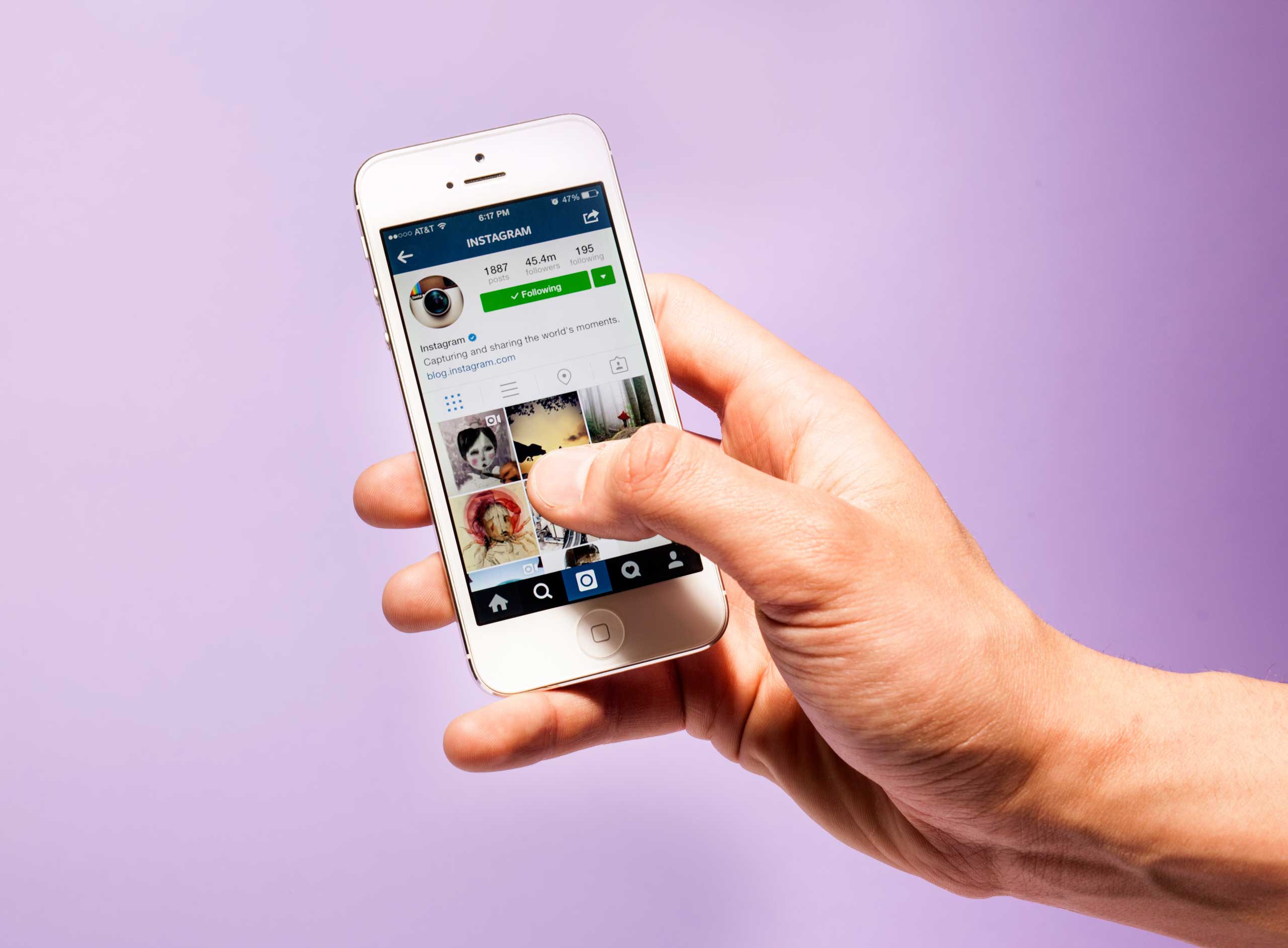

Photography was once an expensive, laborious ordeal reserved for life’s greatest milestones. Now, the only apparent cost to taking infinite photos of something as mundane as a meal is the space on your hard drive (and your dining companion’s patience).

Happiness Guide

<!-- /wp:paragraph --><!-- wp:paragraph -->

But is there another cost, a deeper cost, to documenting a life experience instead of simply enjoying it? “You hear that you shouldn’t take all these photos and interrupt the experience, and it’s bad for you, and we’re not living in the present moment,” says Kristin Diehl, associate professor of marketing at the University of Southern California Marshall School of Business.

<!-- /wp:paragraph --><!-- wp:gutenberg-custom-blocks/unsupported-block {"content":"<newsletter data="health" /> -->"} -->

<!-- /wp:gutenberg-custom-blocks/unsupported-block --><!-- wp:paragraph -->

Diehl and her fellow researchers wanted to find out if that was true, so they embarked on a series of nine experiments in the lab and in the field testing people’s enjoyment in the presence or absence of a camera. The results, published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, surprised them. Taking photos actually makes people enjoy what they’re doing more, not less.

<!-- /wp:paragraph --><!-- wp:paragraph -->

“What we find is you actually look at the world slightly differently, because you’re looking for things you want to capture, that you may want to hang onto,” Diehl explains. “That gets people more engaged in the experience, and they tend to enjoy it more.”

<!-- /wp:paragraph --><!-- wp:paragraph -->

Take sightseeing. In one experiment, nearly 200 participants boarded a double-decker bus for a tour of Philadelphia. Both bus tours forbade the use of cell phones but one tour provided digital cameras and encouraged people to take photos. The people who took photos enjoyed the experience significantly more, and said they were more engaged, than those who didn’t.

<!-- /wp:paragraph --><!-- wp:paragraph -->

Snapping a photo directs attention, which heightens the pleasure you get from whatever you’re looking at, Diehl says. It works for things as boring (sorry, as educational) as archaeological museums, where people were given eye-tracking glasses and instructed either to take photos or not. “People look longer at things they want to photograph,” Diehl says. They report liking the exhibits more, too.

<!-- /wp:paragraph --><!-- wp:paragraph -->

<!-- /wp:paragraph --><!-- wp:gutenberg-custom-blocks/video-jw {"mediaId":"2thy7kCW","autostart":false} -->

<!-- /wp:gutenberg-custom-blocks/video-jw --><!-- wp:paragraph -->

To the relief of Instagrammers everywhere, it can even makes meals more enjoyable. When people were encouraged to take at least three photos while they ate lunch, they were more immersed in their meals more than those who weren’t told to take photos.

<!-- /wp:paragraph --><!-- wp:paragraph -->

Was it the satisfying click of the camera? The physical act of the snap? No, they found; just the act of planning to take a photo—and not actually taking it—had the same joy-boosting effect. “If you want to take mental photos, that works the same way,” Diehl says. “Thinking about what you would want to photograph also gets you more engaged.”

<!-- /wp:paragraph --><!-- wp:paragraph -->

But don’t expect to enjoy yourself more by simply strapping on a GoPro and recording your life. “That kind of technology we don’t think will have any effect,” Diehl says. “It’s when you actively decide what you what to take photos of that you get more engaged.”

<!-- /wp:paragraph -->