In the tidy backyard of Kate Cox’s Dallas-area bungalow, there are two child-sized lawn chairs alongside two toddler bicycles, parked beneath a brick wall scrawled with chalk. There are two red-and-white stuffed horses in the playroom, and two sippy cups sitting in the sink. This is the joyful, messy life that Kate and Justin Cox always wanted. Everywhere you look, there are two of everything. The only problem is: there should have been three.

Last year, the Coxes were thrilled to learn that Kate was pregnant again. They had always planned to have a large family—three, maybe even four kids. When Cox saw the positive pregnancy test in August, she ran into the playroom to tell Justin, who was wrestling on the floor with their three-year-old and 18-month-old. Justin immediately started planning: Would they need a bigger car? What would it mean for their finances? Kate didn’t share any of those worries. She was just excited.

At first, the pregnancy progressed normally. The Cox family designed a little cartoon to announce the happy news to their tight-knit extended family. Kate went to her early prenatal appointments and scans, eager to find out whether the baby was a boy or a girl.

When Cox was around 18 weeks pregnant, she got a phone call from her doctor while she was in the car. “She asked me if I was driving,” Kate recalls. “So I pulled the car over into an empty parking lot.” The doctor told her that the results of early screening tests indicated a risk of Trisomy 18, a life-threatening genetic condition. “I cried for a while in the car,” Cox says. “In the same phone call, she told us that we were having a girl.”

It took weeks of additional testing, appointments with maternal fetal medicine specialists, terrifying ultrasounds, and excruciating waiting before doctors confirmed the diagnosis. “Each time we had an ultrasound, there was more bad news,” Cox recalls, speaking slowly during an interview in her living room in early March. “The neural tube, the heart, the brain, the skull, the limbs. It was hard, because when you looked it was very visible, and you could see on the ultrasound that she wasn't like our other babies. By the end, sometimes I couldn't look at the screen.”

Trisomy 18 is almost always a fatal condition. In rare cases, babies with milder forms of the disease can survive for years, even into adolescence. But Cox’s doctor told her that there were so many malformations to her daughter’s brain, spine, and neural tube that the baby would probably die in utero. If not, she would be placed directly into hospice care after being born, where doctors did not expect her to survive more than a few days. “Every single case of Trisomy 18 I’ve seen has demised—if not in utero, then within hours to days after birth,” says Dr. Damla Karsan, Cox’s Ob-Gyn. “Even if they do survive, the standard of care is comfort care, do not resuscitate.”

Read More: She Wasn't Able to Get An Abortion. Now She's a Mom. Soon She'll Start 7th Grade.

The diagnosis also put Cox’s own health and future fertility at risk. Her pregnancy was becoming increasingly complicated. She went to the emergency room several times for cramping, elevated vitals, and fluid in her birth canal. If the baby died in utero, Cox could get a significant infection. And because she had delivered her first two children via C-section, a third delivery carried increased risk of uterine rupture. If she was induced or had another C-section, her doctor told her, she might never be able to have children again. “The more C-sections you have, the more risk of hysterectomy, hemorrhage, uterine rupture,” says Dr. Karsan. “She was at heightened risk.”

Given the fatal diagnosis and her own medical history, Kate and Justin decided to terminate the pregnancy. “It was really painful, of course, because we wanted our baby so badly,” Cox says. “But we didn't want her to suffer, and the risks to me were too high. I also have two other babies and they need their mommy. So I had to make a decision with all of my babies in mind.”

But abortion is illegal in Texas in all but the most urgent medical situations. Doctors who perform them face immense legal risks. And Cox’s physician told her that because the fetus still had a heartbeat, Cox probably did not qualify for a medical exception. “I couldn't believe that I wouldn't qualify, given the risk I faced in my pregnancy. My baby was not going to live,” she says, pausing to wipe away tears. “So I was really shocked that I couldn't get medical care here in Texas. I wanted to be in my home. I wanted to have my doctors that I trust close by. I wanted to be able to come home and hug my babies, and be close to my mom, and be able to cry on my own pillow.”

But that was not possible. And so, instead of becoming a mother of three, Kate Cox has become an unlikely national figure—the first pregnant woman in the midst of a health crisis to sue for the right to an abortion since the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022. Now, months after she was forced to leave her home state to terminate her nonviable pregnancy, Cox is speaking out in detail for the first time about her experience. She has become a reluctant advocate for reproductive rights, the most prominent example of how abortion bans can endanger even women who desperately wanted to be mothers.

Before this ordeal, Kate and Justin Cox had never thought much about abortion. “I wanted a big family,” Kate says, sitting at her kitchen table, underneath a big print of a Madonna and Child. The living room is scattered with unicorn books; there’s a stuffed Olaf, the snowman from Frozen. “I just didn't think it was going to be something that would ever be in my life.”

The Coxes weren’t especially political in general. Neither Kate nor Justin are reliable voters, they say, and don’t necessarily identify with either political party. Between raising two toddlers and working full-time jobs (Justin’s in IT; Kate works at a nonprofit), they were just “trying to stay afloat,” as Kate puts it. They didn’t pay much attention to the news. When the Supreme Court issued the Dobbs decision, it floated across their radars, but didn’t seem to matter very much to their lives. When Texas’s strict abortion ban went into effect shortly after, neither paid much attention, because they both assumed that there would be medical exceptions. When Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton warned that doctors who provided abortions could be held criminally liable, the news barely registered.

Once Cox’s doctor told her that she couldn’t get an abortion in Texas, Cox started Googling to learn more about the state law. That’s how she came across the Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR), a legal advocacy organization that had filed a lawsuit, Zurawski v. Texas, on behalf of 2 Ob-Gyns and 20 women in Texas who were denied abortion care, asking the court to clarify the scope of the state’s “medical emergency” exception to its abortion ban.

Cox sent a cold email to CRR, and was connected to Molly Duane, a senior staff attorney who is the lead attorney on the Zurawski case. Cox explained that her fetus had a fatal diagnosis and that her doctor had told her that because of her medical history, continuing the pregnancy carried risks for her own health and future fertility. Duane agreed to help her try to obtain an abortion in Texas.

CRR is representing dozens of patients challenging abortion restrictions in multiple states, but Cox’s case was different because she was currently pregnant and in medical crisis, says Nancy Northup, President of the Center for Reproductive Rights.

“Kate was the first time since Roe was overturned that a woman who was currently pregnant, needing an abortion under the health exemption, went to a court to get a court order for an abortion,” Northup says. Her situation, Northup says, exposes how some medical exceptions to abortion bans are written in a way that makes them nearly impossible to apply. “What Kate Cox’s case shows is that this argument of the states that they have exceptions to their blanket abortion bans for the health of the woman is false. They don’t have exceptions, and they won’t allow exceptions to be applied.”

On Dec. 7, a Texas judge granted Cox a temporary restraining order, allowing her to terminate her pregnancy and shielding her doctors from prosecution under Texas law. But almost immediately, Attorney General Paxton petitioned the Texas Supreme Court to halt the lower court’s order, and threatened local hospitals with legal action if they allowed the abortion to proceed.

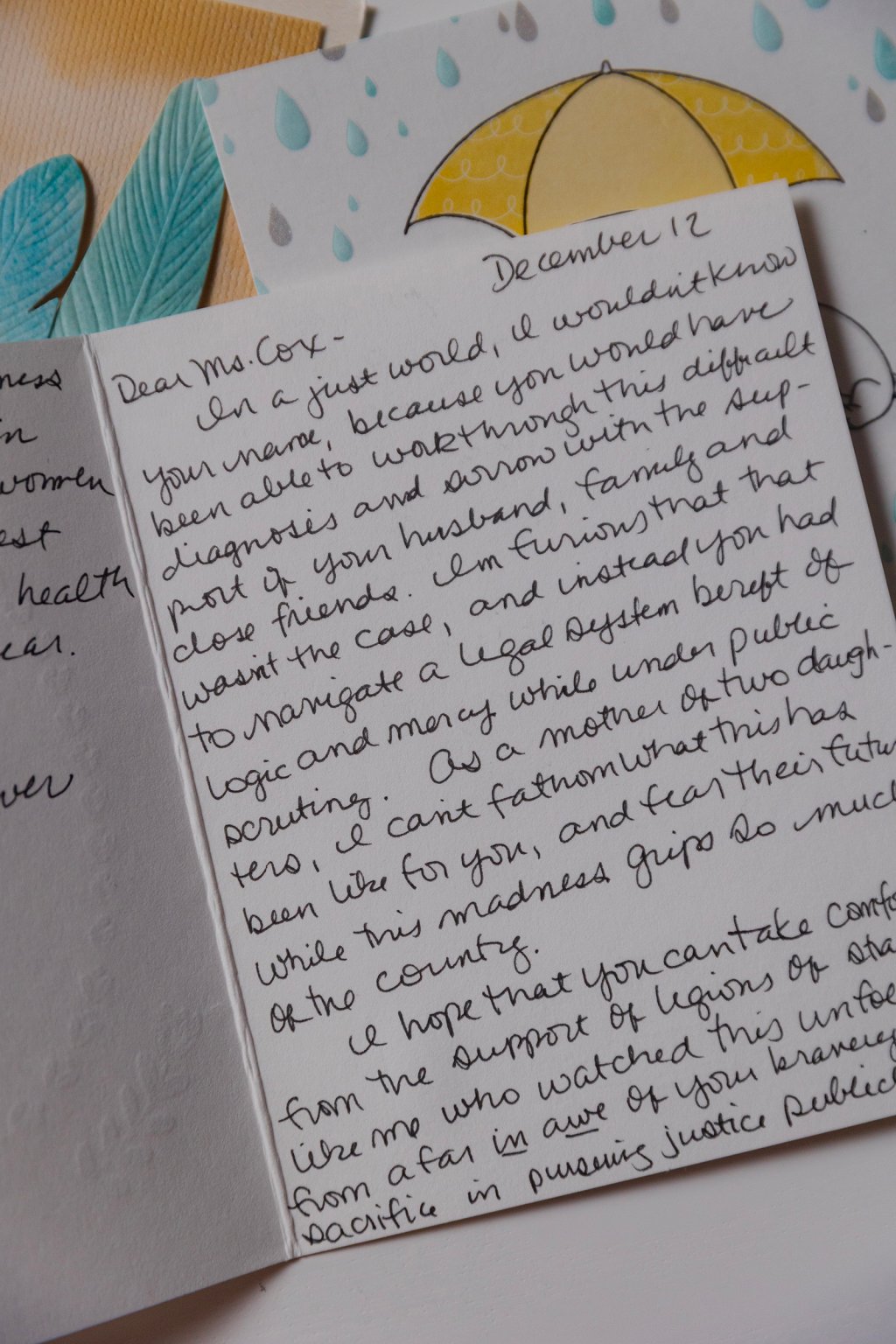

At that point, Kate was roughly 20 weeks pregnant. After a few days of waiting for a ruling from the Texas Supreme Court,she and Justin decided they couldn’t wait any longer. They left their two young children with relatives and went to New Mexico to terminate her pregnancy. On Dec. 12, she was finally able to get an abortion, but only after uprooting her life to travel out of state. “That experience added a lot of pain and suffering to what was already the hardest and most difficult time in our lives,” she says.

Before the termination, they named the baby Chloe Jones. “It was kind of a name that was in our hearts for our next baby girl,” Cox says with a small smile. “And she'll always be our baby.” The middle name was after Kate’s grandfather, she adds, “so that way she would know who to look for in heaven.”

Months later, Cox finally feels like she can talk about the ordeal in detail. She recalls how the weeks between getting the Trisomy 18 diagnosis and finally terminating her pregnancy were excruciating. She would take her children to the grocery store, and people would smile at her and ask when she was due. Acquaintances would ask if she was having a baby shower. Her three-year old daughter was so excited about another sibling; she didn’t understand that there would not be a new baby coming home.

Although Kate did not want an abortion, she says she is “grateful” she was able to get one. “The alternative would have been worse,” she says. “I didn't want to have to wait until my baby died in my belly, or died during birth, or have to hold her in my arms as she suffocates or has a heart attack.”

The experience has opened Kate and Justin’s eyes to the ways their family could be affected by laws that seemed to have little to do with them. “As a nation we have a lot to learn about abortion,” says Cox. “Sometimes prayed for, wanted pregnancies end in abortion. It's medical care.” Kate’s trauma has made Justin think of abortion as much more than a women’s issue. “It impacts the fathers, just like it does mothers,” he says. “Don’t just shut your mind to it and think: this doesn't involve me. If you wait until it impacts you, then it’s too late.”

A few weeks after her abortion, Kate was chasing her kids and her nephew around her house when she saw a missed call from “Joseph Biden.” She thought it was a prank caller or a nasty heckler. But after a few text messages, she realized that the President and First Lady were, in fact, trying to reach her.

Read More: Biden's 2024 Strategy On Abortion.

“I actually had my son on my hip, and he had peed through his diaper all down my side,” she says, laughing for the first time since our conversation began. “I certainly never thought I would get an opportunity to speak to the President. If I did, I didn't think it would be with pee down my side. That's how it goes for moms sometimes.” The President and First Lady “shared really kind words about what we went through as a family,” she recalls, and invited her to sit in the First Lady’s box at the President’s State of the Union on March 7.

Cox says the family doesn’t have concrete plans to do more explicit advocacy around abortion, but she does plan to “continue sharing our story when we can.” She says she’s “grateful” for the Biden Administration’s work on reproductive rights, and supports the work Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris are doing around abortion access.

“I don’t particularly enjoy being involved in politics,” Cox says. Right now, she doesn't have any plans to appear in any Biden ads ahead of the 2024 election. But, she adds: “Never say never.”

And whether or not they choose to be in the public eye, both Coxes say they now plan to become regular voters, a political evolution that reflects the way in which abortion access has transformed from a question of feminist choice into a question of medical necessity. “What I've learned from this experience is that if you are pregnant, if you love someone that is pregnant, if you may become pregnant, you have to vote like your life depends on it,” Cox says. Justin adds that abortion access is now his “number one issue.”

Kate and Justin get up from the kitchen table and slip back into the familiar routine of busy parents with things to do. There’s trash that needs to be taken out, a dog that needs to be walked, two sippy cups that need to be washed. Their kids will be home soon.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Charlotte Alter/Dallas at charlotte.alter@time.com