The Hunger Games themselves feel like a car crash: bloody and brutal but you can’t look away. And the key to that morbid watchability comes from a high school assignment. The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, the new prequel movie joining the hit Hunger Games franchise, examines how the Capitol, which controls the dystopian nation of Panem, convinced its citizens to watch two dozen teenagers fight to the death.

Set during the 10th annual Hunger Games, The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes begins some 64 years before the events of the original trilogy. Capitol citizens have grown bored of the games, which were created as punishment after the districts of Panem lost a bitter rebellion. To boost ratings, Casca Highbottom (Peter Dinklage), the dean of the Academy—a high school attended by the children of the Capitol elite—and Head Gamemaker Dr. Volumnia Gaul (Viola Davis) assign each district tribute to a mentor from the school. Their role, as Highbottom puts it, is “to turn these children into spectacles, not survivors.”

The fulcrum between others’ pain and one’s own pleasure slides dangerously toward sadism. The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes joins a spate of recent pop culture offerings that reckon with this phenomenon, from the reality TV show Squid Game: The Challenge and Nathan Fielder’s The Curse to Jordan Peele’s Nope and Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah’s National Book Award finalist Chain-Gang All-Stars. What does that say about the consumers of this art that creeps closer and closer to reality? What price are we willing to pay for a good show? And what price tag does that pin on performers?

In the movie, conscientious Academy student Sejanus Plinth (Josh Andrés Rivera) insists during a classroom outburst that the real reason Capitol citizens don’t want to watch the Hunger Games is because they know that tributes—and proletariat district residents, for that matter—are people too. His classmate, Coriolanus Snow (Tom Blyth), who will go on to become President Snow in the Hunger Games trilogy, takes that idea and twists it. If they want Capitol citizens to watch, he posits, they need to make things personal. He suggests allowing Capitol citizens to bet on the tributes. They need to feel invested, literally.

Here and elsewhere, to get viewers to care, those in power must work to humanize their performers. But they will always remain just that: entertainers, designed to elicit interest, maybe sympathy, but never true empathy. As we watch a show-within-a-show unfold onscreen or in our pages, though, it becomes increasingly difficult not to become spectators ourselves.

The eccentric and calculating Head Gamemaker Gaul asks Snow to write up his suggestions for increased viewership into an essay assignment. And thus the trademark appeal of the Hunger Games is born: Alongside the betting, Snow proposes sponsorships, in which Capitol citizens can donate to a tribute, and their mentor can use those donations to send them life-saving gifts in the arena.

The 10th annual Hunger Games become the blueprint for the next 65 Games to come. They hire a host for the first time, the flamboyant Lucretius “Lucky” Flickerman (Jason Schwartzman), predecessor of the Hunger Games’ Caesar Flickerman (Stanley Tucci). And they implement televised tribute interviews, one more way of turning them into bonafide reality stars.

Snow develops a connection with his tribute, Lucy Gray (Rachel Zegler), a traveling musician from District 12, where she used to sing of her own free will. Selected for the 10th Hunger Games, she must now sing for her life, in her TV interview. As she does, keening about going to her grave in “a voice husky from smoke and sadness,” donations flash by onscreen. Tears roll down the faces of Capitol citizens. They seem genuinely moved by Lucy’s appeal to empathy—but not quite enough to call off the Games.

The scene evokes the framing of and the reaction to the news in 2023. Israel's military offensive in Gaza has killed more than 11,000 people since Oct. 7, when a deadly Hamas attack prompted the country to declare war. United Nations experts have warned that Palestinians are at "grave risk of genocide." As the war continues, Palestinians are forced to package themselves as worthy of attention, even on the brink of death, writes Dr. Hala Alyan, a Palestinian American writer and psychologist.

“The task of the Palestinian is to be palatable or to be condemned. The task of the Palestinian, we’ve seen in the past two weeks, is to audition for empathy and compassion. To prove that we deserve it. To earn it,” she writes in an Oct. 25 New York Times guest essay. “These days, everyone is trying to write about the children. An incomprehensible number of them dead and counting. We are up at night, combing through the flickering light of our phones, trying to find the metaphor, the clip, the photograph to prove a child is a child.”

Suzanne Collins, the author of the Hunger Games trilogy and prequel, felt compelled to write the series after an experience she had channel-surfing TV late at night illustrated the dissonance. As she flipped from channel to channel, coverage of the Iraq war and footage from a reality TV show “began to fuse together in a very unsettling way,” she told The Guardian in 2012. Both were sensationalized, and thus desensitized. Media framing was blurring the line between pain and pleasure.

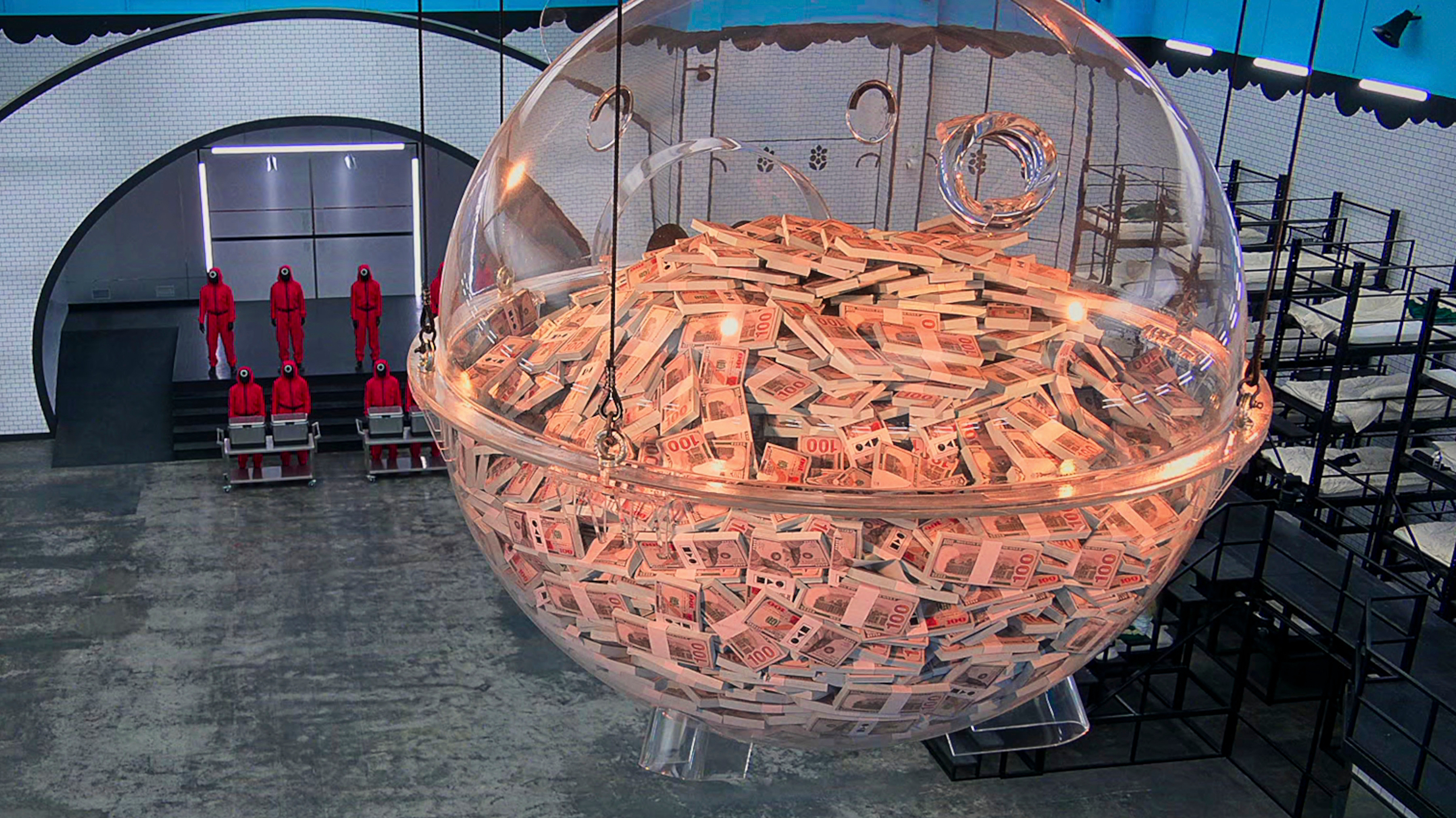

That line is even blurrier today. On Nov. 22, Squid Game: The Challenge, a competition reality TV series based on the 2021 dystopian survival drama, a damning indictment of socioeconomic inequality, will arrive on Netflix. In it, 456 players compete for a $4.56 million prize (without the lethal consequences.)

The original Squid Game creator, Hwang Dong-hyuk, has said that the idea for the smash hit show came from his own life: He couldn’t work, and he, his mother, and his grandmother had to take out loans to survive a global financial crisis. “It’s not profound!” he told The Guardian. “It’s very simple! I do believe that the overall global economic order is unequal and that around 90% of the people believe that it’s unfair.”

To twist Hwang’s concept—456 people playing games to the death for 45.6 billion Korean won—into a reality TV show misses the point entirely, bringing viewers over the line from mere observers to actual participants. Placing real people in a Squid Game simulation implies that viewers didn’t just relate to protagonist Seong Gi-hun’s (Lee Jung-jae) struggles—to some degree, they enjoyed watching him suffer and inflict suffering.

In the first Hunger Games movie, Katniss (Jennifer Lawrence) and Gale (Liam Hemsworth) sit in a field just outside of District 12 on the morning of the Reaping, the day that tribute names are drawn. “Just one year,” Gale says, “what if everyone just stopped watching?” “They won’t,” Katniss replies. “If no one watches, then they don’t have a game,” Gale says. “It’s as simple as that.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com