Rick Scott wants to know what I think of the speech he’s about to give. “Pretty aggressive, right?” he says with a bashful grin.

The Republican senator from Florida has just walked into the Conservative Political Action Conference, where he’s about to throw another punch in his ongoing and increasingly one-sided battle with Senate GOP Leader Mitch McConnell. The speech he’s preparing to deliver is indeed aggressive, calling out McConnell by name, enumerating a laundry list of alleged failures, and charging his own party’s leaders with “destroying our country” as surely as the Democrats. “We can’t put up with this B.S. anymore,” Scott will say, to a smattering of cheers. “I’m seeking to become the least popular man in Washington. And I’m happy to report I’m making great progress.”

Over the past couple of years, Scott has transformed from rank-and-file Republican in good standing to self-styled bête noire of the GOP establishment. It began with his stewardship of the party’s Senate committee in last November’s midterms. What was supposed to be a slam-dunk election cycle ended disastrously: Scott presided over a botched fundraising strategy, fielded a slate of awful candidates as a result of his insistence on staying out of primaries, and released a personal policy platform full of unpopular ideas that continues to bedevil his colleagues and provide fodder for Democratic attacks. (One GOP operative described it to me as “third-rail sh-t.”) When President Biden spoke in Florida in February, his team distributed copies of Scott’s plan, which they say would threaten Medicare and Social Security.

Scott capped it all off by running against McConnell for party leader, an act of breathtaking chutzpah in a chamber known for loyalty and decorum. It was the first time McConnell, whose 16 years atop the conference make him the longest-serving party leader in Senate history, has ever faced such a challenge from within; even Sen. Ted Cruz, at the height of his government-shutdown bear-poking days, never took such a step. Scott was rewarded for his trouble by losing his spot on a high-profile committee. One McConnell loyalist I emailed for comment on Scott replied, simply, “Ass clown.”

Scott professes to be thrilled by such reactions. A multimillionaire former hospital-company CEO, he was elected to the Senate in 2018 after two terms as governor of Florida, and, like many former executives, finds it a deeply frustrating place. “In business, you just say, ‘Okay, what do you want? Let’s figure out if I can do a deal,’ he tells me. “This is totally different.” You’d think, he says, that every Senator would have a say and be encouraged to represent their state. Instead, he laments, “I don’t get asked my opinion. Most people don’t get asked their opinion.”

Sitting in a bare-walled dressing room in the bowels of the Maryland convention center that’s home to CPAC this year, Scott tells me there’s nothing personal about his jihad against McConnell. He’s just consumed with determination to change things for the better at a time when they seem to be falling apart. “Here’s what I personally believe,” he says. “I don’t get why the public’s not mad about what’s going on in this country. I really don’t get it.” At a time of surging political violence, bitter polarization, and constant vituperation, just a couple of years out from a violent insurrection, I haven’t heard many politicians say we’re suffering from a lack of anger in our politics. But Scott is insistent. If people were as angry as he thinks they ought to be, they’d be showing up at congressional offices, flooding the polls, barraging him with emails and phone calls. “In the rest of the world, when inflation gets like this, poor people protest,” he says. “Why aren’t they protesting?”

More from TIME

To Scott, his crusade against the GOP establishment is a form of protest. His critics see it as a product of his ambition and arrogance. In the Senate GOP’s closed-door, secret-ballot leadership election last November, he did not come close to unseating McConnell. But the 10 votes he got represented a fifth of the conference, deepening the fissures that have crippled the party for years. He has laid down a marker that he plans to continue to be a thorn in McConnell’s side on looming battles over the debt ceiling and government spending. And he has set a question echoing through the staid corridors of Washington: What, exactly, is Rick Scott’s endgame?

Many in D.C. speculate he plans to run for president—chatter some in Scott’s orbit have stoked. But when I ask him, Scott denies it: the only thing he’s running for in 2024 is reelection to the Senate, he says. Others suspect he’s angling to cozy up to Trump, who has his own ongoing beef with McConnell, but Scott tells me he’s not planning to take sides in the looming face-off between the former President and the current governor of Florida, Ron DeSantis: “I’m not endorsing.” (This despite the fact that Scott’s relationship with his successor in Tallahassee is a chilly one. “I don’t know him, actually,” Scott says of DeSantis. “He never talks to me.”) All he’s trying to do, Scott insists, is get Washington focused on the right things. “I wanted to create a conversation about where we’re going. It didn’t have to be my ideas,” he says. “But I do believe that we ought to be fighting over what we believe in, and then run on things. I ran on a plan in 2010, 2014, and 2018, and I’m going to run on things this time too. And I believe that’s how you win elections.”

It’s time for Scott’s speech, and he strides out onto the stage, into the blinding lights of the massive CPAC ballroom. As a speaker he is about as electric as an electric eel: technically electric, yes, but capable of delivering only a mild shock to the human body. Nevertheless, it’s testament to the state of today’s GOP that there’s no better red meat for the base than attacking the party’s most prominent officials. “Many in Washington have quietly advised me to apologize for taking on Sen. McConnell, so everyone can settle down and we can get back to business as usual in Washington,” Scott says. “I would like to apologize…to absolutely nobody!”

To hear Scott tell it, he is utterly blameless for the electoral debacle that cost Republicans the Senate last year. A combination of factors beyond his control, he argues, created unexpected difficulties for the GOP, from contentious primaries that left Republican nominees bruised and broke to the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade. “And then, if you look on our side, we didn’t really have something to run on,” Scott says. “We hadn’t blocked any of the Democrat issues. We hadn’t passed legislation on the Republican side. We didn’t have enough of a what-we-are-for.”

Scott and I are chatting in the dining room of his D.C. crash pad, a $2 million, four-story row house around the corner from his Senate office. The attention-getting decor—dramatically flowered wallpaper, statement chandeliers, a zebra-print stair rug—he attributes to his wife, Ann, the high-school sweetheart he married at 19. Scott has heard that McConnell, his fellow multimillionaire, also has a place on Capitol Hill, but he’s never been invited to it, he tells me.

For all his talk of fury, Scott, 70, does not come off as angry in conversation. He is tall and thin and pinkish-white, with a dusting of short white hair at the temples of his otherwise bare head. He has an odd demeanor, intense yet soft-spoken, outgoing yet slightly shy. He seems like a man who finds difficult things for most people laughably easy, and things that are easy to most people impossibly difficult. Friends say he so rarely eats that they sometimes pack snacks if they know they’re going to spend a long time in his presence. The overall effect is of a friendly alien: a creature who, while not quite human, has been studying our species for years and finds us fascinating.

The Scott-McConnell feud traces back to November 2020, when Scott volunteered to serve as chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee (NRSC). As the only candidate, he was elected unanimously by his fellow GOP senators. Sources who know both men say they were not the best of friends but not known to be enemies either; McConnell, with his reputation as a ruthless and focused political strategist, would never have allowed an avowed foe to take the post that could determine whether or not he regained the cherished title of majority leader. Republicans had high hopes for the midterm election cycle, which seemed likely to deal a backlash to the party in power and featured Democratic incumbents or open seats in numerous swing states.

Read More: Trump’s Indictment Showcased His Rivals’ Weakness.

Indications that the two men would butt heads emerged quickly. In January 2021, as McClatchy first reported, Scott’s adviser Curt Anderson emailed a group of fellow GOP operatives to share an article blaming McConnell for the results of the 2020 elections. Things went downhill from there, as Scott brought in his own team to run the committee and rebuffed outside help, including from McConnell. Other senators and operatives who offered advice or assistance were told their services weren’t needed, according to four sources familiar with the committee and its operations. ”It was a total bunker mentality,” says a former top NRSC official, who reeled off a lengthy critique of the committee’s operations off the top of his head, from its digital operations to its staffing structure to its polling.

The committee struggled with money, making a massive investment in digital fundraising that largely failed to bear fruit. When Scott took the reins, the NRSC had $14 million on hand and $9 million in debt; after raising and spending $235 million, he left it with $8 million on hand and $20 million in debt. And crucially, Scott declared that the committee would not play favorites in Republican primaries, leaving the party with several underqualified nominees who went on to lose winnable elections.

“I think it was the worst NRSC I’ve seen since at least 2008”—when Republicans lost eight Senate seats—”and I’ve heard many senators say the same,” says Ward Baker, who served as the committee’s executive director in 2014 and 2016, gaining and keeping the majority both times. “It was a total failure of leadership, and when things went bad [Scott] blamed anyone else but him.” When Baker was in charge, he says, he spoke to McConnell or his team virtually every day. “They boasted about it: this was their committee, they were in charge, it was the Rick Scott show and the Rick Scott team. That’s fine, but you can’t then say it’s not your fault.”

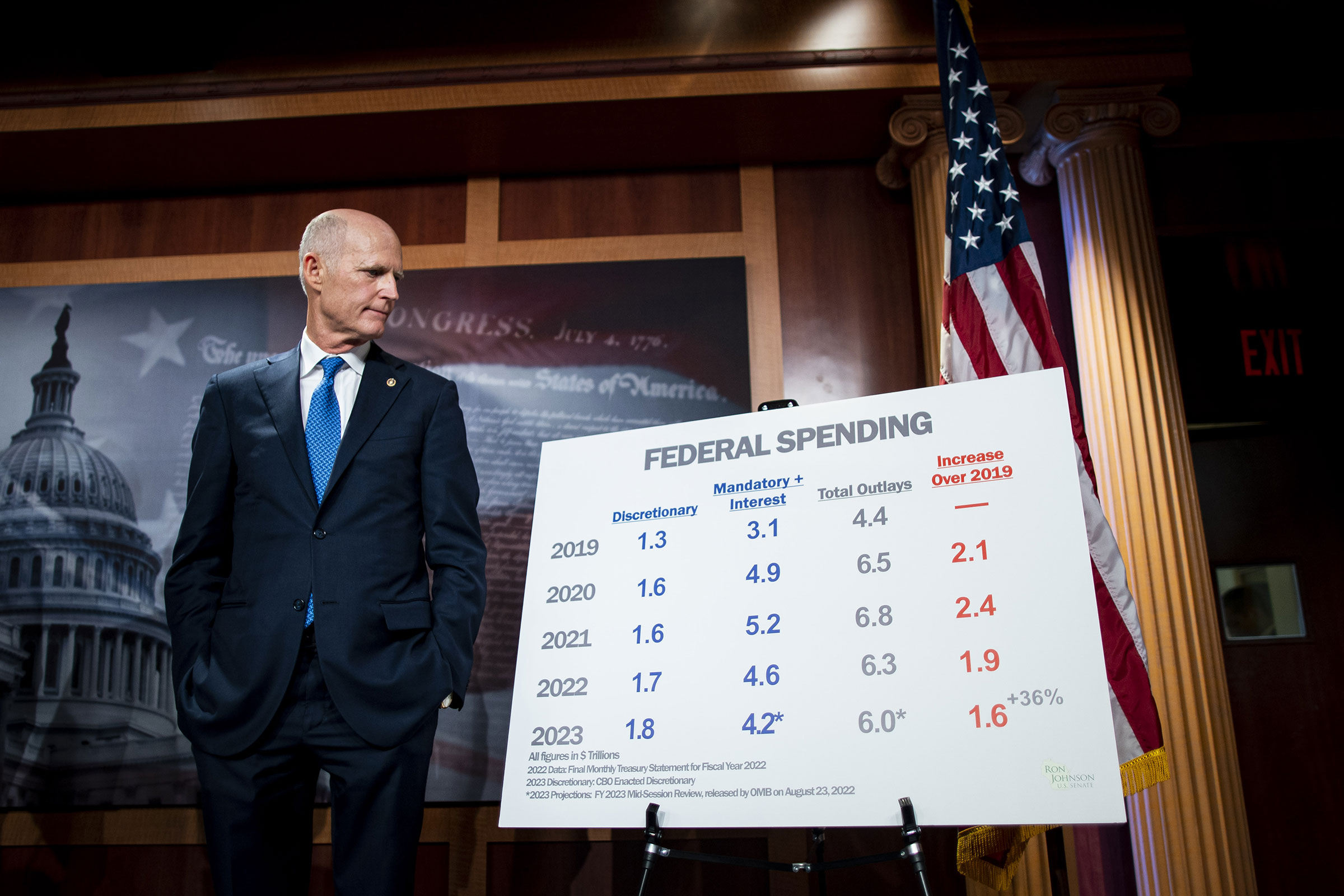

One of McConnell’s rules of politics is that the opposition party should focus its campaign on the flaws and missteps of the party in power. Scott disagreed: In February 2022, he released his “Plan to Rescue America,” with planks ranging from education (“Our kids will say the pledge of allegiance”) to border security to election integrity. Scott’s policy proposals quickly came under attack from Democrats, who pointed out they would raise taxes on the poor and potentially lead to the termination of popular programs. Democrats weren’t the only critics. McConnell, too, disavowed the platform, publicly declaring that he considered it toxic for the party and its candidates.

By this point, the two men were openly at war. Things would only get worse as the cycle progressed, with McConnell repeatedly denigrating the chances of the party and its candidates. (McConnell’s office declined to comment for this story; a source with ties to the Senate leader says he tried but failed to dissuade Scott from releasing the policy platform, and only went public with his criticisms when Scott refused to listen to him privately.) “Unfortunately, that was the Scott plan. That’s not a Republican plan,” McConnell told an interviewer. “I think it will be a challenge for him to deal with this in his own reelection in Florida, a state with more elderly people than any other state in America.”

Those who know Scott were not surprised to see him go his own way and wave off the doubters. His life is a rags-to-riches story of impressive proportions. Born in Illinois, Scott grew up in Kansas City, where he and his four siblings lived in public housing. His mother divorced his abusive, alcoholic father when he was young, and he was later adopted by his stepfather, a truck driver. He bought his first business, a donut shop, while still in college at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. In the 1980s, he began buying hospitals, eventually using acquisitions and mergers to create the nation’s largest healthcare company, Columbia/HCA, with 350 hospitals in 38 states. “You could tell this was a guy who really came up with nothing,” says Bill Rubin, a Tallahassee-based lobbyist who represented Scott’s interests at the Florida legislature. “He has tremendous focus and he works very hard toward what he feels he needs to do. Everything he’s done, he’s done himself.”

But his aggressiveness had a downside. In 1997, Scott was forced by the board to resign amid a federal probe of the company’s operations. Investigators charged that the company inflated diagnoses, faked expenses, and gave kickbacks to doctors in order to bilk the government. The company pleaded guilty to 14 felonies, and the resulting $1.7 billion in settlements for Medicare fraud were the largest in American history. Scott, whose departure settlement amounted to more than $300 million, has denied wrongdoing and said he was not a target of the probe. In 2003, he moved to Naples, Florida. A few years later, when health-care reform began to be debated in Washington, he reemerged as an opponent of socialized medicine.

Florida GOP elites had already coalesced around a candidate, then-attorney general Bill McCollum, when Scott decided to enter the 2010 race for governor. It was the year of the Tea Party, and Scott tapped the anti-establishment fervor and opposition to health-care reform that were in the air. He spent lavishly, putting $67 million of his own money into narrow primary and general-election victories. As governor, he slashed spending and regulation and balanced the state’s budget while also making illegal immigrants eligible for in-state tuition and enacting gun restrictions after the Parkland shooting. In the wake of the financial crisis and recession, he toured the country to drum up business for Florida. Rick Perry, who was then the governor of Texas, fondly recalled the two men competing to see who could create the most jobs for his state. “I enjoyed greatly kicking his butt in that contest,” Perry says, “but he was always a very good sport.”

Scott’s relationship with the Republican-led legislature was chilly and sometimes contentious. He ran for reelection in 2014 on a promise to accept the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion, but then reversed himself when he won and the GOP’s political winds were blowing in the other direction—the rare example of a politician flip-flopping in order to do the unpopular thing. “He’s a friendly guy, a nice guy, but he is not a team player—he sees himself as the chief executive,” says David Jolly, a former Florida Republican congressman who supported Scott in his 2010 run. “I don’t think he’s ever felt like he’s gotten the respect he’s due.”

“Rick Scott is completely persuaded of his own brilliance, and he has three tough election victories to show for it,” says Joshua Karp, a Democratic consultant who has worked in Florida. “He doesn’t care how he’s portrayed; he’s willing to endure bad publicity in service of his long-term goals. It has not made him popular or well-liked in his own party, but politically it’s definitely an asset. There’s a little bit of honey badger in there.” Another former NRSC official puts it more sharply: “He’s not a good politician. It’s actually kind of a compliment: he has no charisma and no real following, no natural gifts whatsoever, yet he has won three elections through sheer will and hard work and willingness to spend lots of money.”

Term-limited out of the governorship in 2018, Scott set his sights on the Senate, challenging longtime Democratic incumbent Bill Nelson in a good year for Democrats nationally. Scott’s friend Bobby Jindal, the former governor of Louisiana, recalls cautioning him at the time that he might not take to the gig. “As governor you’re the closest thing in politics to being CEO of a company. The Senate has a different pace,” Jindal says. “But he was optimistic he was going to do it differently. His attitude was, ‘I’m not going to spend several years building seniority. Just like I brought a different attitude to the governor’s office, I want to bring a different attitude to the Senate.’ He was going to recruit like-minded senators or help them get elected and make big changes.”

As someone who remembers what it was like to go up against the GOP establishment in a rough-and-tumble primary, Scott tells me, he was determined from the outset that the NRSC would not take sides in such contests. “I was not the establishment candidate,” he says. “I was not supposed to win any of my races.” As a result, he says, “I believe the voters ought to choose—I don’t think Washington ought to choose candidates.”

In the end, it was mostly Trump who chose the party’s Senate candidates, haphazardly bestowing his endorsement on an oddball crop of inexperienced candidates like Herschel Walker in Georgia, Mehmet Oz in Pennsylvania and Blake Masters in Arizona. On the eve of the election, sources say, Scott’s aides were boasting that they expected to win not just those races but also long-shot contests in Colorado and Washington state, both of which they lost by at least 10 points. Republican House candidates won the popular vote in 2022 by 3 percentage points, while the party’s Senate nominees ran consistently behind.

Read More: How Democrats Defied History In the 2022 Midterms.

In a tense three-hour closed-door meeting in November, some Republican senators decried Scott’s management of the campaign and demanded an audit of the committee. Many also pointed fingers at Trump, who turned around and blamed his old foe McConnell. Scott quickly jumped on board, announcing his challenge to McConnell in a Nov. 15 letter to his colleagues. “Some believe we constantly give in to the Democrats and have no backbone,” he wrote. “Some believe we should not make deals with Chuck Schumer that a majority of our Conference members disagree with. Some question why we are presented large spending bills we have never read or had input into and are expected to vote for them on short notice to prevent a government shutdown. … And then there are some that are happy with the way things are going.”

In our interview, Scott offered an example of what set him off. In April of 2021, he recounts, he successfully proposed that the senators adopt a rule mandating that they wouldn’t vote for any debt-ceiling increase without structural spending cuts. “So McConnell goes out in July and says we’re not going to give them any votes to raise the debt ceiling,” he says. “By September, he comes into lunch and says, ‘We worked out a deal, we’re not going to have to vote for the debt ceiling, we’re just going to let the Democrats do it without us.’ We got nothing. There’s no structural change, no reduction in expenditures. Nothing. Was there even a conversation about it? No. We gave in.”

There is something to Scott’s critique of McConnell. For all his fearsome Washington reputation as the “Grim Reaper” for Democratic priorities, the Kentucky senator has revealed a different side in the past two years, supporting or tacitly blessing a number of bipartisan deals, including bills on infrastructure, China, and gun control, which give Biden a roster of legislative wins to boast about as he campaigns for re-election. McConnell has made deals with Schumer to fund the government and raise the debt ceiling, even appearing with Biden at a bridge in Kentucky to tout the project’s funding in the infrastructure bill. The man Democrats feared and loathed in the Obama years, and decried as a cynical operator who would sell the country down the river if he thought it meant a marginal advantage in the next election, has lately looked more like a dealmaking institutionalist.

But the GOP has been rather flamboyantly moving in the opposite direction. And Scott believes his views are closer to the party’s base.

Scott picks his way down the carpeted hallway of the enormous CPAC venue, pausing periodically for selfies with fans, shaking hands with hotel staffers, CPAC volunteers, and second-tier MAGA figures like the former Trump national-security official K.T. McFarland. An aide trails behind with an armful of glossy booklets, handing out copies of his policy platform. (Three photocopied sheets of paper have been stuck in the front of each booklet, “clarifying” some provisions for which Scott feels he was unfairly attacked and adding a 12th point to the plan. “NOTE FOR PRESIDENT BIDEN: This plan cuts taxes,” one page reads. “Nothing in this plan has ever, or will ever, advocate or propose, any tax increases, at all.”)

Down a backstage hallway, at a door marked VIP ROOM, Scott greets Matt Schlapp, the embattled chairman of the organization that hosts CPAC, who was recently accused of sexually assaulting a Walker campaign staffer, and Chris Ruddy, the CEO of the far-right cable channel Newsmax. Once inside, he falls into conversation with Steve Moore, the former Trump Administration economic adviser. “I’m trying to get everybody together to actually get a deal done, but nobody cares,” Scott tells Moore. “They want to just do nothing and raise the debt limit!”

Moore shakes his head in agreement. He mentions the CHIPS Act, last year’s massive semiconductor-manufacturing bill, which the Biden Administration is now using to try to get companies to provide child care for workers. “You didn’t vote for that, did you?”

“No, I fought it!” Scott says. “A year ago, my first filibuster—they were so mad. We stopped it for a year!”

Moore turns to me and points at Scott. “This guy is the fiscal conscience of the United States Senate!” he says. “But that’s not a high bar!” Turning back to Scott, he laments the Senate GOP’s collective lack of spine. “So you’ve got you and four or five others,” Moore says.

“Yeah, there’s about six of us,” Scott says. The problem with his colleagues, he says, is bigger than just not being willing to vote their principles. It’s a larger lack of courage. “It’s not so much that they even vote with us, it’s that nobody wants to be vocal about it,” he says. “You’ve got to vote the right way and you’ve got to be vocal about it.”

Though his fellow Senate dissidents may be small in number, the challenge to McConnell revealed a caucus more divided than previously known. “Rick offered an approach that I think would be helpful, harnessing the ideas of each member of our conference to make sure we don’t shut most members out of the process,” says Sen. Mike Lee of Utah, a Scott ally who similarly traces his political roots to an anti-establishment primary challenge in the 2010 Tea Party cycle. Just attacking the other side, Lee says, doesn’t serve the people or the party well. “We knew it was a long shot, and he didn’t get elected, but I think it’s important to have these conversations, and I’m grateful that Rick was willing to do it,” Lee tells me.

Whether out of ambition, patriotic concern, or sheer boredom, Scott is clearly determined to continue making trouble in the Senate, consequences be damned. “Challenging the leader, he can count, he knew going in what the outcome was likely to be,” Jindal says. “I don’t think he saw it as a single battle. I think he saw it as part of a bigger process—not just for Rick, but for Republicans across the country who are frustrated.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Molly Ball at molly.ball@time.com