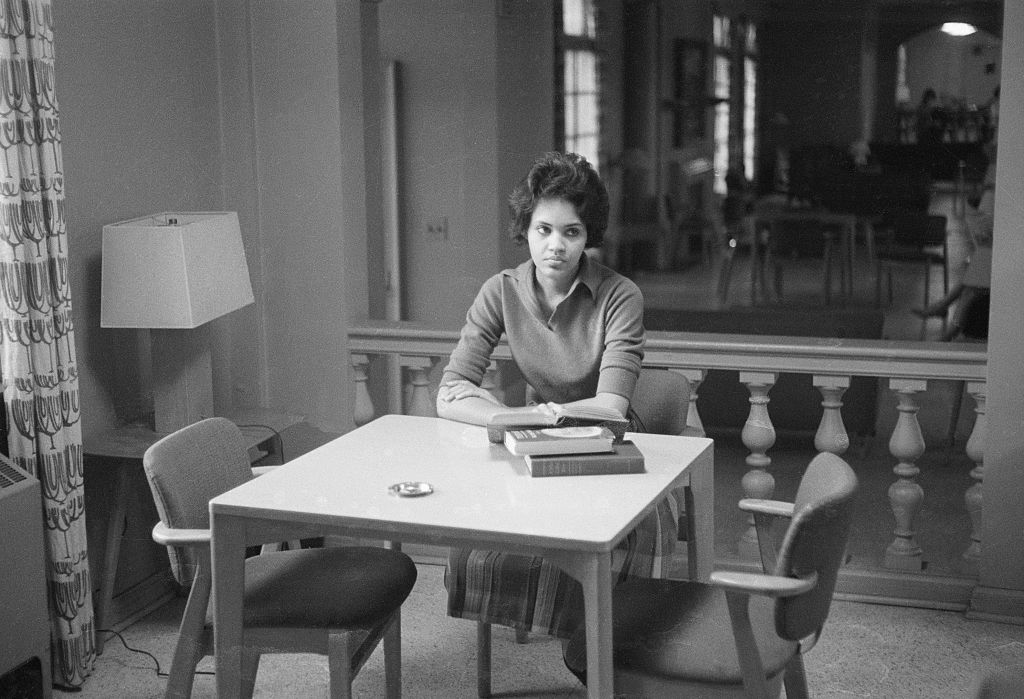

Charlayne Hunter-Gault, 80, has both made and chronicled history in real time. After becoming the first Black woman to enroll at the University of Georgia in 1961, in the 1970s she was one of the earliest Black women to write for the New York Times—establishing the paper’s Harlem bureau—before becoming NPR’s chief Africa correspondent. Among her many other accomplishments, she was also the first Black staff writer at The New Yorker, and her efforts to capture the American story have netted awards including a pair of Emmys and a Peabody.

And history, she tells me while discussing her new book, My People: Five Decades of Writing About Black Lives, tends to repeat itself. That, she says, is something she took away from one of her early journalism classes at the University of Georgia, where a professor added that we learn from history precisely because we so often fail to do so. History should be a guide past avoidable social and political calamities, she says, and it should offer hope in the face of deeply distressing current events—reminders that at even in our darkest hours, there have always been “heroes and she-roes,” as Hunter-Gault puts it, who pulled the rest of us toward something better. Even so, we all too often experience the present as disconnected from the past. My People counters that instinct with essential insights gleaned from observation of a messy world.

Hunter-Gault spoke to TIME by phone from her home in Martha’s Vineyard. The following transcript of our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

TIME: What made you want to put together a collection of your reported work at this particular moment in time?

HUNTER-GAULT: While this is a very challenging time, we have stories in our history that should be helpful to people who are getting despondent over where we are now. We have had challenges in the past, going back to the first time people of color landed in this country, and yet look where we are. I think this is an important time to share some of that history, not only for our people, that is, people of color, but for all people. While my book focuses primarily on Black women, there were white women and men who died for us. And so I’m hoping that looking at our history, we can see the heroes and she-roes—many of whom are ordinary people who would probably reject being called a hero, and yet they were.

The book includes a story about a community-dispute center in Harlem, one about parents looking for a way to teach their children a more accurate version of history, one about the late Congressman John Lewis when he was a young voting-rights activist, another about policing during periods of increased crime—do you feel those stories include themes on the issues of the moment requiring more thought?

Well, why don’t you quote yourself on that? Yeah.

Ha! I probably should not have phrased my question that way.

Again, I’m trying to put our history in context. I have a perspective that is based on my own history, which [involved] a bit of challenge, but also was full of determination. And so I look at that history, and I say how important it is—for this younger generation in particular, but for some of the older ones, too, who are getting a bit frustrated with where we are in the country—for them to know the history, [to] know what shoulders they stand on.

Another thing that stood out as I was reading through the stories in the book is that there are quite a few profiles of people who, at the time you wrote about them, did not yet have massive national stature. One of them was about the future Congressman John Lewis, the impact of the 1964 Voting Rights Act, and what he expected to come from his work registering Black voters in Georgia. Is there something that you see as a consistent element among those who ultimately shape American life?

Remember what Barack Obama said, when he went to Selma, [Ala.]. He said, we stand on the shoulders of giants. Yep. People don’t always realize that these giants were little boys, like John Lewis was when he used to go and preach to the pigs in the backyard.

I do remember what was in the back of my mind [in 1961] when I was at UGA and John [Lewis], and a group of Black and white people, young people, boarded a bus in Washington to come to the South and challenge the interstate segregation rules. And here’s what got me. Not only were they coming into what clearly was going to be a dangerous situation, or potentially dangerous, but they were gonna do it anyway. They were so determined that they signed their wills before they left Washington, in case there was a problem. And of course, that, again, led to the person who received the first blows for freedom—[one of whom], of course, was John Lewis, when he got off the bus and these white agitators beat the hell out of him. And did it stop him? No, it inspired him.

I’ve listened to the commentators on various channels, about how democracy, in effect, is going to hell. Somebody said something about how, if you look around the world, democracy is failing everywhere. But we have history that shows us that we can be successful in our efforts to perfect unions, not only in America, but in other places like South Africa where I have a lot of history. There’s just so much pessimism about democracy.

Read more: Why John Lewis Kept Telling the Story of Civil Rights, Even Though It Hurt

There are people who would say that, before the 2016 election, there were warnings that if you elect a person to the highest office who has openly said he will not accept the election results if he doesn’t win, you are playing a very dangerous political game. Many of those people happen to be people of color—journalists and historians of color, aware of what portions of our history pointed that way. And they were largely dismissed.

I’ll tell you a story, briefly, that I’m still trying to figure out. [In 2020], I went to a neighborhood that is predominantly Black. I ultimately got to talk to these guys [in a park]; one of them had voted. And when I asked him would you mind telling me who you voted for? He said, Well, let’s put it this way. I didn’t vote for Trump. So I said okay, so then I went to a businessman who has a wonderful sidewalk cafe, and he [said] something to the effect of, ‘Why are they always on him about his taxes?’ [The man thought Trump was] a good businessman who’s a good example for him as a businessman. The New Yorker ran it that Monday [before Election Day]. When the vote came out, by the time they analyzed it, that was absolutely correct: there were Black people who voted for Donald Trump.

Is there anything going on in the world today that you think is under-covered or not getting enough attention?

It’s one thing to report on demonstrations and the work of organizations like Black Lives Matter and so forth. But it’s another thing to report on the underlying issues that cause those organizations to exist, that cause those protests. I see news organizations making changes and adding people of color. And it’s one thing to add people of color, which I applaud. It’s another thing to make sure to add people of color who understand the dimensions of the race problem and who have contacts within the community.

Edward R. Murrow, years ago, said this instrument [television] can teach, it can illuminate, it can inspire—but it can only do so to the extent that we are willing to use it to those ends. “Otherwise, it’s nothing but wires and lights in a box.” And I quote that all the time.

I’m going to put that up next to my computer. It’s an excellent prescription. I’m curious, though, when you looked at your own body of work, were there issues or areas where you felt you still had work left to do?

Something we have to work on is how you communicate with people you disagree with. I see that reported, especially when it comes to history and how you teach it and what you include. The question I have about that is how do we, as a nation and the people of the nation, communicate—because I don’t see a lot of communication between people who have one set ideas and people who have a different set. I think that’s one of our biggest challenges.

But again, the lessons from my own history are lessons that I think are equally applicable today. And I think that rather than be intimidated into not reporting on people of color and their issues, people in our profession in particular should be encouraged by our history—the good, the bad, the ugly—to report on those issues. I do remember a conversation I had with my editor when I went to the New York Times. Before I was hired, I went for the interview and he asked me, if I was sent to Harlem, would I be able to tell the truths about Black people? He agreed eventually, and I set up office on 125th [Street], in a small room, big enough for me.

I continue to work because I still believe in the profession and what it can do, which is one of the reasons I just did a piece on the Wampanoag. I have perspective and I still see things that I think I can give some prominence to. And while I’ve slowed down on all of that I don’t plan to not do it anytime soon. I found another story where a young Black woman is working on helping to educate young students about how best to communicate with people who don’t agree with you, and one of the people who spoke along with her was a white teacher who is implementing those things in her curriculum.

We’ve just got to continue to emphasize the notion of what it takes to create a more perfect union. And, to be sure, information—good information—is what’s going to take us there.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com