LaTasha Hyatt has worked to turn out Black Alabama voters for seven years. The program director at the Carver Museum in Dothan, Alabama, Hyatt organizes voter engagement efforts, works on voter education, and canvasses every election to get out the vote. She says she’s often asked the same question by Black voters: What’s the point?

“When you go out canvassing, you come into contact with a lot of disgruntled African Americans,” Hyatt says. “They don’t feel like they have power anyway. You have to push past that lackluster energy to encourage folks to vote.”

This year, Hyatt says that energy could be even harder to combat, as Alabama’s congressional map has been contested up to the U.S. Supreme Court over whether it structurally dilutes Black voting power in the state.

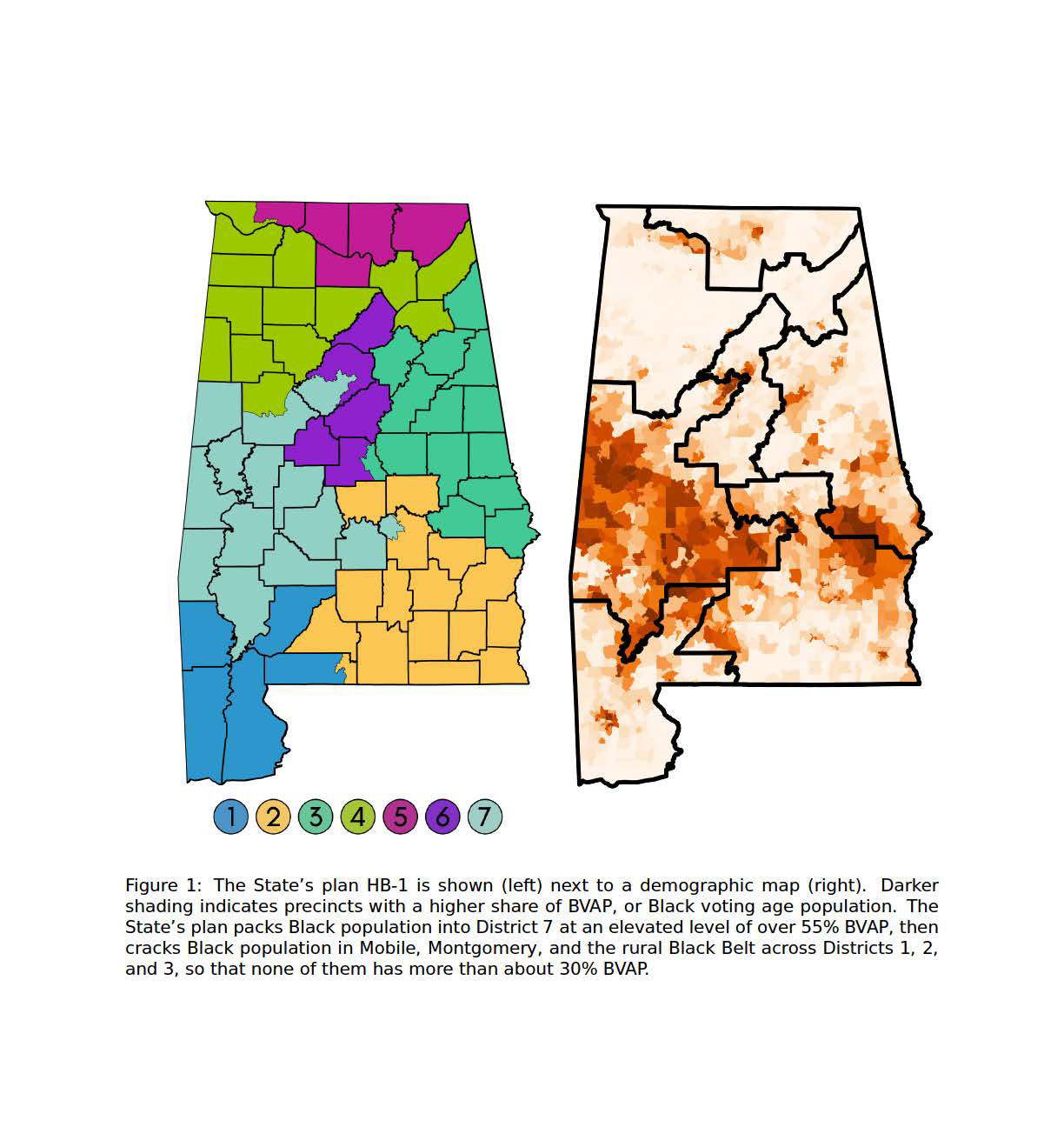

In November 2021, Alabama’s Republican Governor Kay Ivey approved newly drawn federal congressional districts based on the 2020 census. The seven district map—which was drawn by 15 white Republicans and six Black Democrats in the state legislature—contains only one majority-Black district, despite the fact that Black Alabama voters make up around 26% of the state. Several Black Alabama voters and advocacy groups challenged the map, arguing it violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits state governments from limiting voting on the basis of race, including through “vote dilution” by either intentionally carving up communities of color up among districts or squeezing them all into one. The challengers argue that the 2021 map illegally “packs” most of the state’s Black voters into the 7th Congressional District and “cracks” the remaining Black voters in Mobile, Montgomery, and the rural Black Belt into Congressional Districts 1, 2, and 3.

In January, a panel of three federal judges—two of whom were appointed by former President Donald Trump—agreed. They not only ruled that “Black Alabamians are sufficiently numerous to constitute a voting-age majority in a second congressional district,” but also concluded that “Black voters have less opportunity than other Alabamians to elect candidates of their choice to Congress.” The panel ordered the state legislature to toss out the map and go back to the drawing board to create either another majority-Black district or “an additional district in which Black voters otherwise have an opportunity to elect a representative of their choice.”

More from TIME

But Alabama appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court—which voted 5-4 in February to reinstate the map until it issues its ultimate ruling on the case. The Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the case on Tuesday, and the outcome could bolster or gut what remains of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Alabama argues that the district court’s order to draw a second majority-Black district amounts to “racially segregating” Alabama voters and thus violates the Constitution. The plaintiffs argue that race has long been one of many factors map-drawers might use to delineate communities of interest when redistricting. On Tuesday, the court’s conservative justices appeared unswayed by Alabama’s arguments for race-neutral redistricting, although they also appeared inclined to maintain the original map. (The Alabama Attorney General’s Office did not respond to TIME’s request for comment.)

Read More: The Supreme Court Could Gut the Voting Rights Act Even Further

The Supreme Court may not issue its answer on the legality of Alabama’s map until next year. But in the meantime, Alabama voters will head to the polls in November in districts that a federal court already ruled likely illegally diminishes Black voting power, and whose ultimate fate remains uncertain.

Several Black Alabamians tell TIME that the situation has motivated them to ramp up ‘get out the vote’ efforts as a way to channel their frustration and anger. But Hyatt worries it may make it more difficult to convince others to participate, given that three federal judges confirmed what many already suspected: Black Alabamians may have less power in elections than white Alabamians’. “You cannot tell Black voters that the system is not against you, when we do make these strides and it clearly seems against us,” says Hyatt. “We still have to pay the same amount of taxes. We still have to do the same things as everybody else. But we don’t have as much of a voice.”

‘We have to stay on this battlefield’

Acquanetta Gaston Poole, the 64-year-old Alabama State Organizing Manager with the voting rights nonprofit Black Voters Matter, says she’s been thinking a lot about history as she follows her state’s redistricting battle.

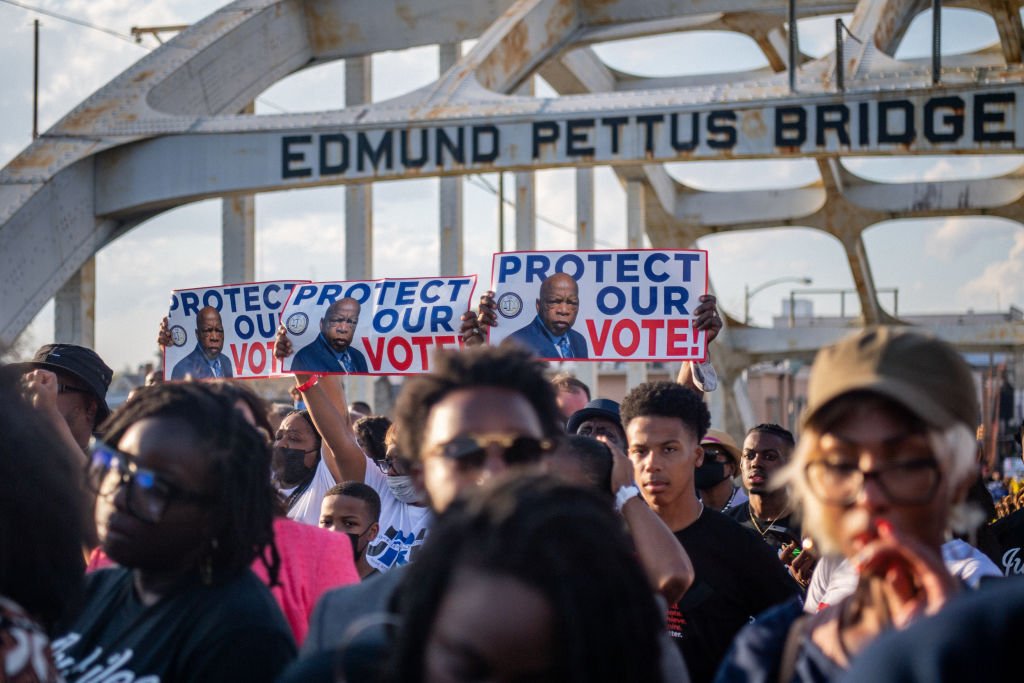

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was in many ways birthed by the struggle of Black civil rights activists in Alabama, who marched from Selma to Montgomery to protest racist Jim Crow voting laws and caught the attention of the entire country. “The only way we can make a difference is to get people to vote,” Poole says. “And they’re making that so difficult today. But we have to stay on this battlefield.”

John Merrill, Alabama’s Republican Secretary of State and the chief defendant in the lawsuit, tells TIME that it’s important to remember that Alabamians can choose to live “wherever they can choose to live.” “The fact that people are mobile, and that they can live wherever they choose, makes it difficult to put people in particular districts if you’re just trying to assign them by race,” he says.

Chastady Perry, 37, lives in Congressional District 2, one of the districts that the lawsuit alleges “cracks” communities of Black voters and dilutes their voting power. Perry, like Poole, says she’s recently been reflecting on the “many injustices that our parents and grandparents faced.” But Perry also says her frustration has motivated her more than ever to try to get out the vote.

Linda Tullis Sellars, 66, in Birmingham, feels similarly. “It almost makes me want to run for office, if you want to know the truth,” Sellars says. “Because I want to see a change in the democratic process in my state.” Scottie McClaney, 58, also in Birmingham, says that when she’s trying to fight a sense of pointlessness when it comes to voting, she reflects on the state’s past. “It’s just been a tradition, a history, for our parents to take us to the polls,” she says. “I was taught to vote. People died for us to vote.”

What comes next

Regardless of whether or not the Supreme Court ultimately agrees that Alabama’s districts engage in illegal vote dilution, the 2022 election results will stand.

This is standard practice when it comes to challenging redistricting maps, says Jeffrey M. Wice, a professor at New York Law School who specializes in redistricting. The Supreme Court could in theory order a new election with a new map to take place in 2023, but that’s extremely unlikely. More likely, if the Supreme Court rules the districts are illegal, the legislature would be sent to create a new map—which could in turn be challenged in court all over again. This cycle has been repeated in states like North Carolina and Texas for decades, and the litigation can take many years before reaching a final resolution. Litigation over North Carolina’s map drawn in 1992 was last ruled on by the Supreme Court in 2001—meaning nine years of elections occurred while the map was litigated.

Experts say that cycle can perpetuate injustice. Even if the Supreme Court agrees with the district court and orders Alabama to draw a second majority-Black district, Black voters might still be at a disadvantage, because whoever is elected this year in the current map will have the benefit of being the incumbent, Wice argues. But based on Tuesday’s oral arguments, legal experts say it seems more likely that the high court upholds the map, although potentially on narrower grounds than Alabama is requesting.

Hyatt of the Carver Museum says she’s frightened by the possibility that the Supreme Court could leave Alabama’s new map in place. But “this is why we have to do the work,” she says. “This is why we have to get loud. Because Black voters are not feeling heard.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Madeleine Carlisle at madeleine.carlisle@time.com