Constance Kassor didn’t expect her new class on “Doing Nothing” to be such a hit.

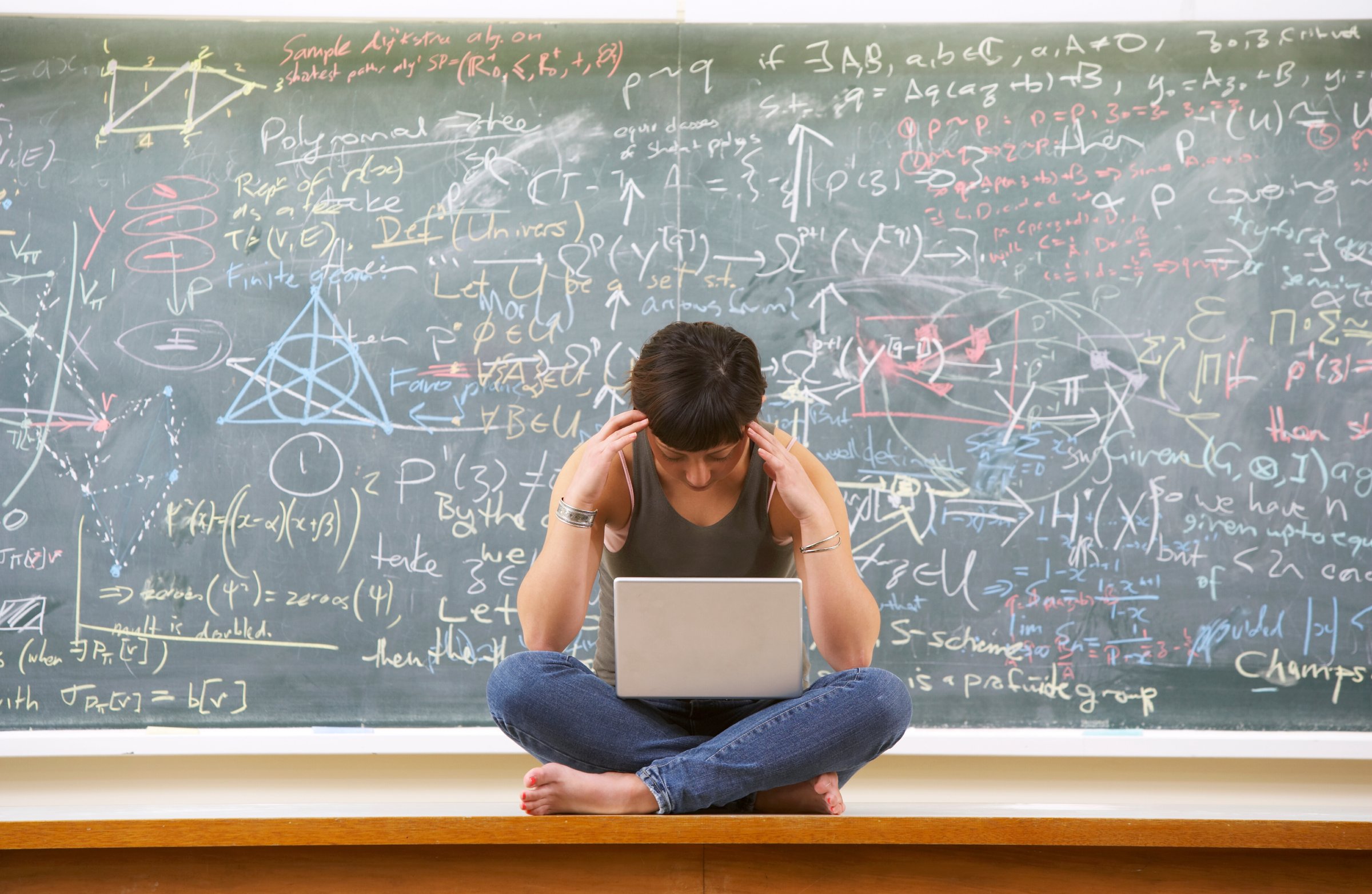

But the course, which teaches students how to relax and unplug, is now the most popular class at Lawrence University. For Kassor, an associate professor of religious studies, that suggests students are seeking out skills that can help them combat stress in the face of mental health challenges and a growing pressure to be productive.

“There’s a real hunger for this among students,” Kassor says. Fifty-two students are taking the class this term—more than any other course at the small liberal arts school, which enrolls about 1,500 students in Appleton, Wis.

“This should tell us something about the current state of college students,” Kassor said Friday in a tweet about the course, which sparked debate about what students need and what universities should teach. The tweet went viral, attracting more than 134,000 likes and 8,000 retweets.

Mental health challenges have been a growing problem on college campuses in recent years. More than 60% of college students met the criteria for one or more mental health problems in 2020-21, a roughly 50% increase compared to 2013, according to a study published in June.

And young people today are also more connected than ever before. Nearly half (46%) of teens say they are online “almost constantly,” compared to 24% of teens in 2014-15, according to a survey by Pew Research Center conducted in April and May 2022.

It might not be surprising, then, that disconnecting and “doing nothing” has gained traction. “Nothing is harder to do than nothing,” Jenny Odell wrote in her 2019 book, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. “In a world where our value is determined by our productivity, many of us find our every last minute captured, optimized, or appropriated as a financial resource by the technologies we use daily.”

Kassor, similarly, worries that too much of higher education is focused on optimizing students for the workplace. Her class meets for one hour, once per week, and is graded pass-fail. Students are expected to show up, leave their phones outside the classroom, and participate, but there’s no final exam.

“It’s really designed as a way to give students the space to slow down a little bit, and our hope is that then they can carry that into the rest of their lives,” Kassor says.

She spoke to TIME about creating the course and why she thinks it’s necessary today.

TIME: What led you to create this course?

KASSOR: This course was a collaborative idea that some colleagues and I have been talking about for the last few years. We’re seeing how stressed out, overburdened and overworked our students are. And we’ve been trying to figure out ways to get them to develop the skills they need to intentionally relax. Studies have been done that show that things like meditation and getting enough sleep, or even just standing up from your desk, or allowing yourself to be bored—these are things that can improve our quality of life. They can improve our creativity. They can help us think more deeply. But these are skills. They’re things that need to be learned.

Why do you think this class is resonating so much with students right now?

I don’t know if it’s a result of the pandemic. It’s too early to say what the long-term effects of the pandemic are. But I think students are really recognizing that they need to make time to slow down and allow themselves to be bored and put their phones down. I think there’s this awareness that they can’t be on all the time. They can’t be productive all the time. So I think there’s a lot of excitement for this class, where they feel like they’re given permission to relax a little bit.

Is there a reason why students need this kind of course today, more than in previous years?

Year by year, I’m seeing more and more 18-year-olds who are showing up to class, and in the first couple of weeks of their time in college, they’re already stressing out about their GPAs and what’s going to go on their resume, and how are they going to get a job after they graduate. I don’t know if it’s the pandemic. I don’t know if it’s social media. I don’t know if it’s parental pressure or the economy. I don’t really know what the driving force is, but I’m seeing a definite trend in the incredible pressure and stress that students are feeling.

What do you want students to learn from this class?

One of the things that we really want students to get out of this class is that we want them to have a space where they can be fully themselves, where they can be present—not just physically, but also mentally and emotionally. Because I think this is kind of antithetical to what’s being asked of them a lot of the time. It’s really designed as a way to give students the space to slow down a little bit. And our hope is that then they can carry that into the rest of their lives, into the rest of their college career, into their work life after they graduate. And that’ll make them better people, more empathetic people, more creative people, deeper thinkers.

What does the “Doing Nothing” curriculum include?

Each week is taught by a different member of the faculty. One of my colleagues from the psychology department came and talked about sleep hygiene, and she shared with students some research that’s been done on the correlation between the number of hours of sleep that students get and their GPAs. It turns out, if you get seven or eight hours of sleep per night, on average, you have a higher GPA. She had students work through creating a plan to make sure that they get enough sleep. We had a dance professor come in and take students on a mindful walking activity. Everybody had to go outside for 30 minutes without looking at their phones, without talking to anybody. We’ve got somebody coming in to teach Tai Chi next week. We’re going to do some meditation. The course is titled “Doing Nothing,” but we’re actually doing quite a bit.

What does the popularity of this class tell us about the current state of college students?

One, that students are really stressed out and overworked and overburdened. Also, I think it tells us that students are aware of how stressed out they are and how much is being asked of them. And there’s a real hunger for this. It’s only worth a sixth of a normal class. It’s not like it’s something that is going to fulfill their graduation requirements. This is really an extra thing that students are making time for. And the fact that so many of our students have opted into doing this, I think, really shows that there’s a need for it.

Some of the responses to your tweet were more critical, with some questioning the seriousness of this course. What is your response to that?

One thing I’ve been trying to emphasize to some people is that this isn’t something that students are being charged extra for. It’s not something that faculty are being paid extra for. I think this is something that is really needed. I think the value of a liberal arts education is not just to prepare students for a job, but it’s to prepare them to be human beings in the world. Even if you’re in a STEM field, you have to be able to communicate the things that you know to people. You have to know how to write. I think this class takes that even further. You have to be able to know yourself well enough to know when you’re pushing yourself too hard, to know when you’re approaching that burnout point. You’re not going to be good at your job if you’re burnt out or if you’re not getting enough sleep.

What do you think would be different if more college students were learning these skills?

If this sort of thing could be normalized, and if students knew that they didn’t have to be on 24/7, that they didn’t have to be productive, that they could take some downtime—I think we would have happier students. We’d have lower rates of depression and anxiety among students. At institutions like mine, we’re concerned with retention. We have students who show up and then for whatever reason, they feel that they can’t continue. And I think this would help tremendously with that, not just at my institution, but at a lot of places.

Given that there seems to be an appetite for this kind of class, is there a lesson you think universities should be taking from that?

I think we need to get away from the idea that we’re just training people to be productive workers. We’re actually giving young people the tools that they need in order to thrive in the world and be good people in the world, and contribute to society in more than just economic, work-related ways.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Katie Reilly at Katie.Reilly@time.com