I was binging yet another of Netflix’s dime-a-dozen puzzle-box mystery shows recently when I felt a pang in my gut. One character was revealed to be a grown-up version of a seemingly distinct character, seeking an arguably unethical vengeance for a decades-old transgression. I wanted to call my mom. “Which episode did you figure it out?” I would ask. And her answer would be, most likely: “Within the first five minutes.”

I can’t call my mom because she died, 10 years ago, on the second day of May. The last day of her life, the worst day of mine. She was 63. I was 26. She was done with being sick but not with living. I was done fearing the worst but not ready for it to happen.

She died six weeks—seven episodes—before the resolution of the murder at the center of The Killing, a series my mystery-loving mother had followed obsessively and one of the few she couldn’t solve on her own. To this day, my dad finds the injustice of the finale’s timing unforgivable. The irrational but totally warranted bones the bereaved get to pick.

Read More: The Memories That Sustain Me on Mother’s Day

My longing for even the most mundane conversation about plot twists is heightened this time of year. She left us—no, she was taken, for it’s wrong to imply there was any agency in her leaving—the same week as Mother’s Day. A blessing: two days to remember her, huddled close together on the calendar each year? A curse: a time for sorrow when everyone else—or so it seems, but of course it isn’t—is celebrating? A little of both.

She breathed her last breath, slow, uneven, on a day I remember as the most magnificent yet that season: violet and buttery yellow crocuses smattering the dewy lawn, and lilacs, her favorite, just beginning their brief but glorious annual recital. A day too beautiful for death in all its hideous corporeal detail. A blessing? A curse? A little of both.

This month marks a decade of Mother’s Days without her. The first seven, before I became a mother myself, brought a bitter cocktail of grief and resentment. Instagram was a yearbook of the best (living) moms of the year, each thumbnail photo a grain of salt in the wound, though I knew no one meant their odes to their mother’s brisket or bear hugs as a personal affront to me. My inbox was two weeks’ worth of reminders not to forget mom this year, encouraging me to spend money to prove how much I loved her. “Thanks, these slippers will look great on her headstone!” I wanted to respond. “Do you make these bathrobes in size dead?”

Read More: The Pandemic Has Meant I’m Rarely Away From My Children. Am I Still More Than a Mom?

The past three Mother’s Days have been different. Now when I see brands’ appeals not to forget Mom, sometimes I think of myself as the honoree before I remember to be indignant on her behalf. Now there are my own quotidian efforts to acknowledge—the 10,000th chicken nugget microwaved, bottom wiped, wet raspberry thwomped across a warm, squishy belly—and they demand some of the real estate once squatted upon by sadness alone.

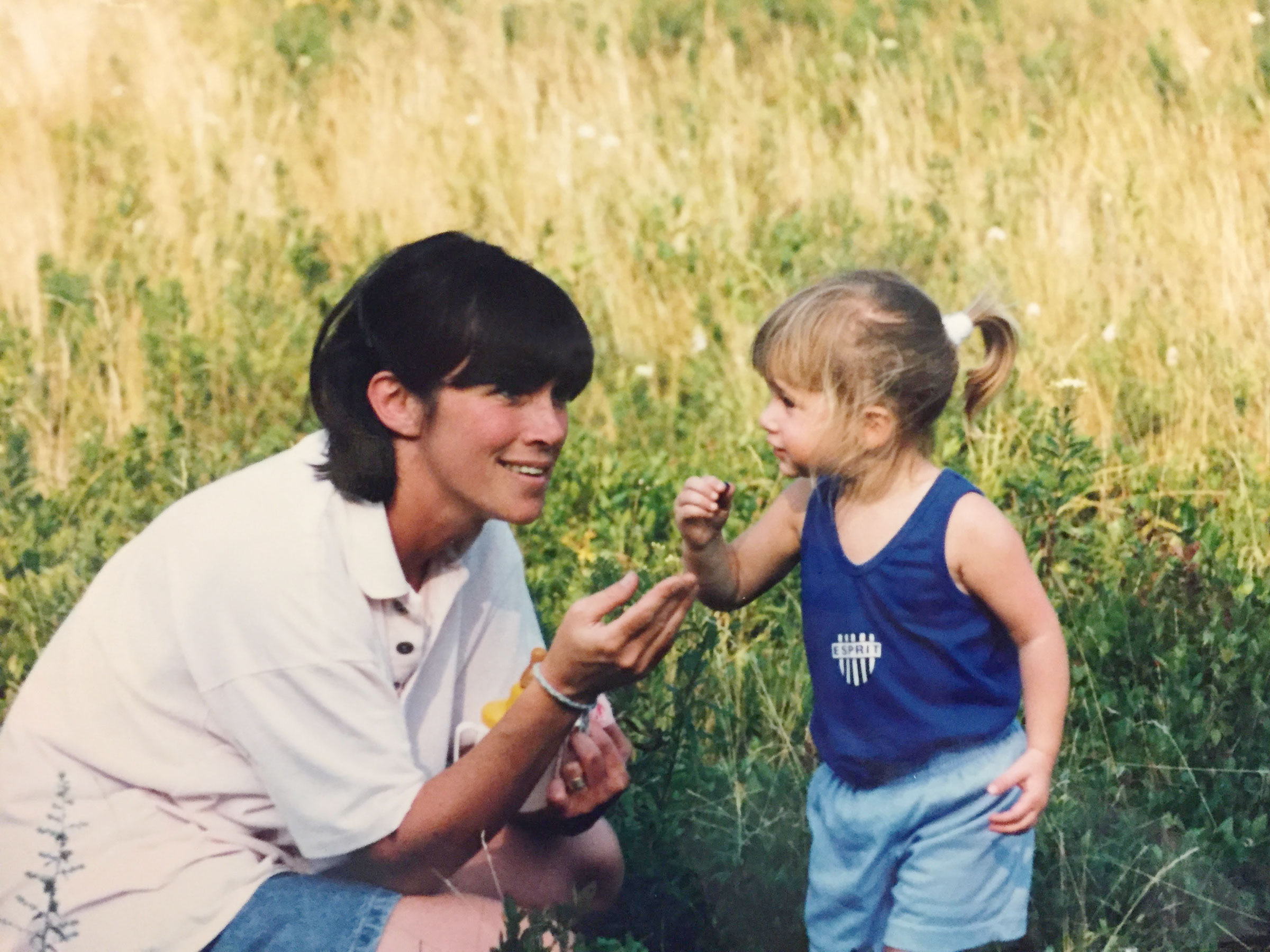

But sharing this day with my dead mom heightens that sadness, too: for only since becoming a mom twice over do I understand, and more with each passing year, what she gave—and gave up for—me. She wanted motherhood; it was a core part of her identity. But it wasn’t everything. And now I know how I, her third child, must have demanded that she redirect even more time and energy from her own self-actualization, her career, her hobbies as an artist and craftswoman and puzzle solver, to raising the three humans she and my dad brought into the world.

I didn’t know enough to ask her about it then, and I can’t ask her about it now—how did you manage to keep your cool when I willfully defied your simple directions for the eighth time in six minutes? Worse yet, I can’t thank her and know she understands it’s a gratitude that can come only from having stood, covered in poop and spit-up and up to here in exasperation and worry, in the very same trenches.

Read More: The Problem With Celebrating the Selflessness of Mothers

Lately I’ve consumed a rash of time-travel narratives, thanks largely to the serendipity of their proximate release dates. In Emma Straub’s This Time Tomorrow, Emily St. John Mandel’s Sea of Tranquility and another Netflix puzzle-box show, Russian Doll, characters travel back in time and change the events of the past, whose ripples in turn sometimes change the present. What would I do if I could go back for one day? The answer is obvious: I’d travel back a few years before the second cancer diagnosis and demand that she schedule an elective surgical removal of the organs, no longer essential, in which those insidious cells would soon proliferate like so many microscopic assassins. So that she might be here now, to bake brownies with my children, and her five other grandchildren, and let them lick the bowl. To finish the Sunday crossword and hike in the woods with her dog, to experience how significantly the Internet has evolved when it comes to her love of bargain hunting, to write scathing social-media diatribes against politicians she never got the chance to hate, to air-dry on a dock after a summer swim in the lake, then watch the sinking sun streak its surface sherbet-orange and pink.

But if for some reason it wasn’t that kind of time-travel story but the kind in which the future is immovable, I might return instead to a Thursday night circa 2000. Sit next to her on the couch with a bag of microwave popcorn as the familiar DUN-DUN of the Law & Order theme song plays. Squint through my fingers as a grisly corpse flashes across the screen, the first critical clues emerging as my homework waits on my desk to be finished. I’d watch for the glint in her blue-gray eyes as they light up, barely looking up at the screen from the knitting in her hands, with the knowledge of whodunnit. Check my watch: five minutes in.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com