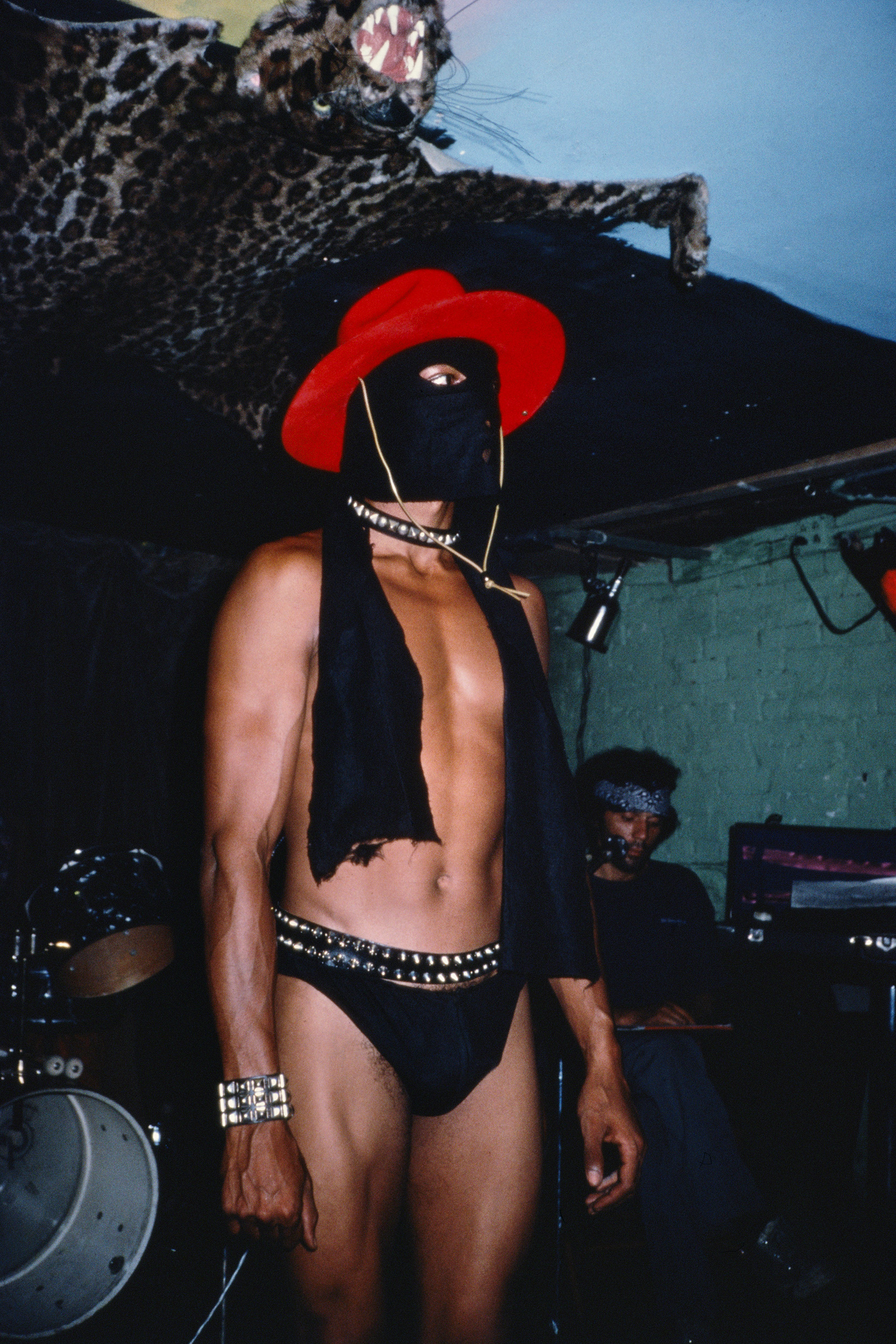

In the summer of 1984, photographer Arlene Gottfried met a man who called himself Midnight at a Lower East Side nightclub, where he was dancing. He invited her out the next night to see him perform before the live drums and poetry at Miguel Piñero’s Nuyorican Poets Café. The image she captured of him that night in a mask would become the first of hundreds of photos Gottfried would make of Midnight over the next two decades, in what amounted to a diary of his life and their complicated relationship.

Surrounded by Gottfried’s photographs in a Chelsea gallery, Midnight feels slightly overwhelmed. He loses his breath when he begins to recount the stories of many people who are gone. “It is very difficult,” he says, “because they were very close friends—Miguel and Arlene.”

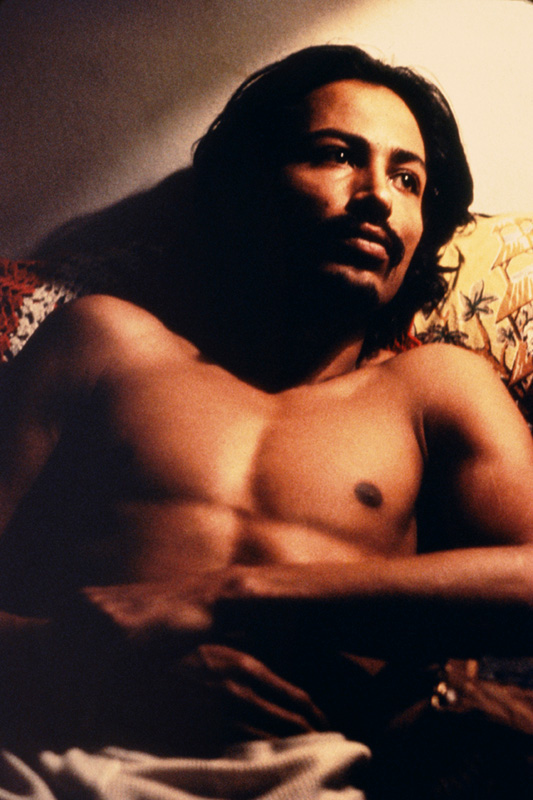

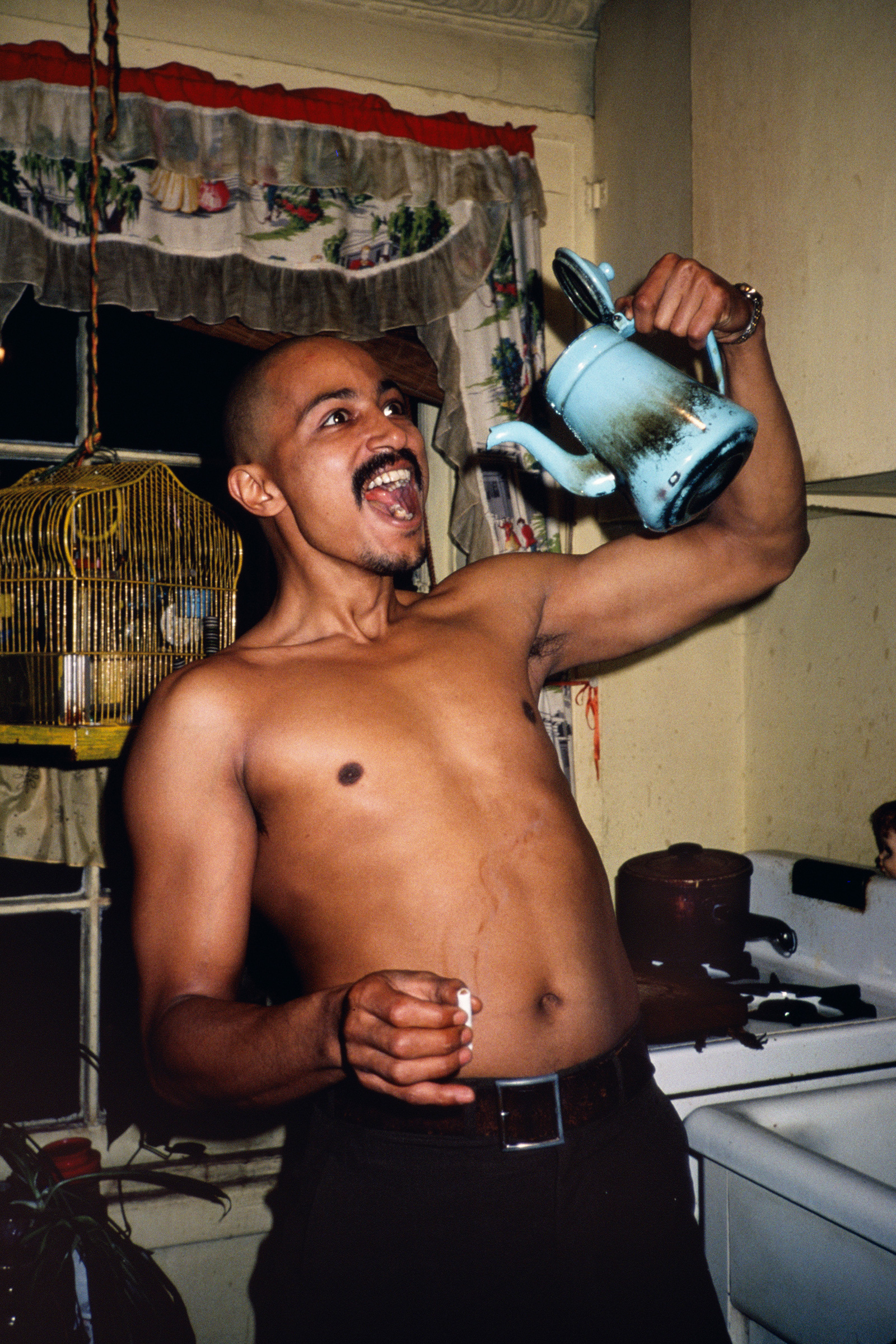

“I was about 25 years old at the time when Arlene came in and started snapping,” he recalls, “and that’s when I knew I was going to have a friend.” What captivated Gottfried is right there in the photos: an incredibly handsome, stylish, and sexually uninhibited man.

A date followed. “We made arrangements to meet the next day. She wanted me to see Shakespeare in Central Park. We got very close at that time. We went down to the lake, and we were kissing, and I told her I wanted to be her friend, and from that day on, we were, and she would take my picture.”

In September, Midnight moved in. “Arlene had a Rolodex, a million friends, and invites every night,” recalls Midnight. Gottfried was busy working on assignments for publications like The New York Times Magazine, Fortune, and LIFE. She tried training him as a photo assistant. “She would pay the rent, and I would pay for food, clean, run errands like, pick up cameras, film,” says Midnight.

“We were deep friends when we weren’t lovers,” says Midnight. “Whatever she did, I wanted to do. It was one photo after another for our entire relationship.”

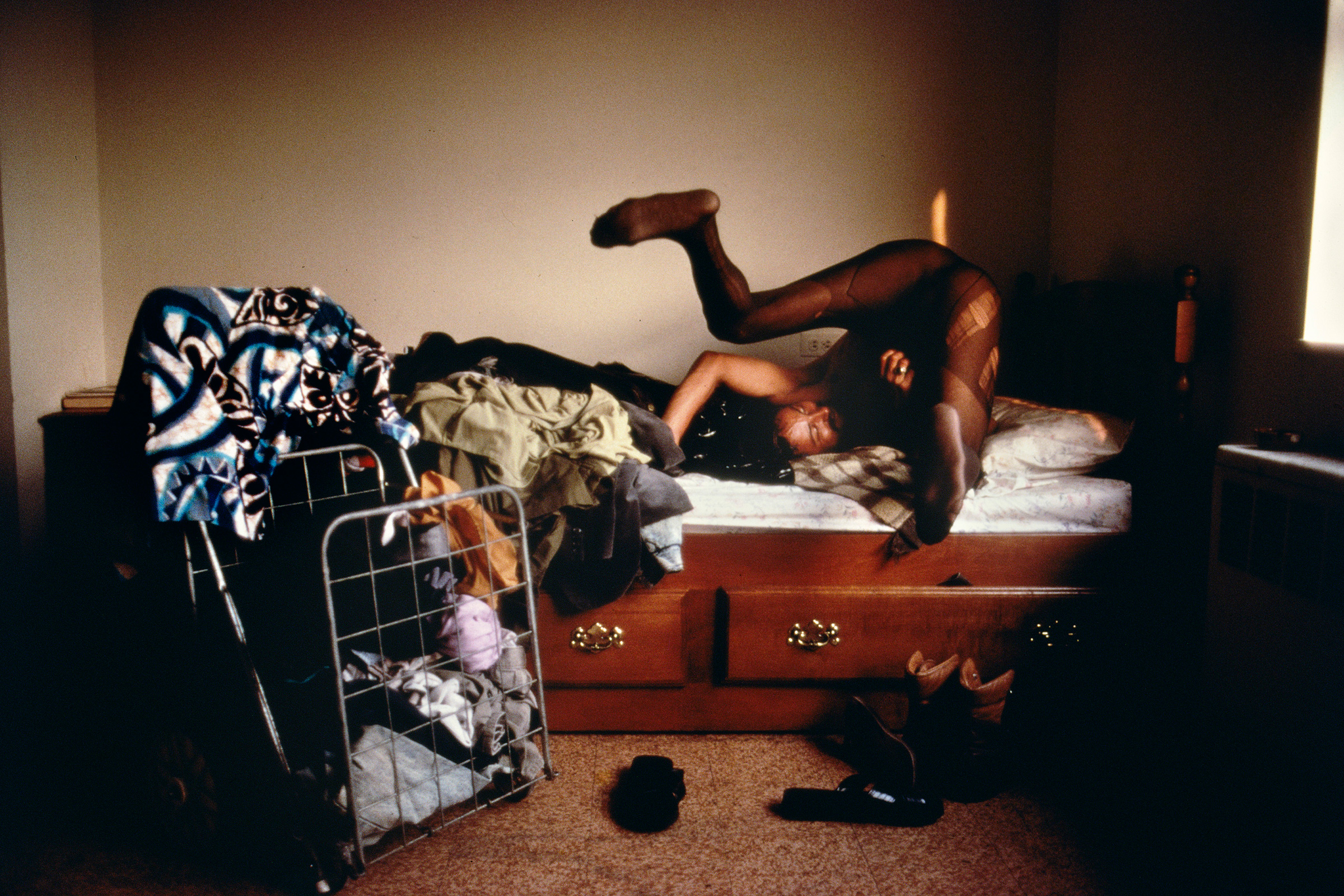

In that first year, things quickly became complicated. “I would disappear,” says Midnight. In her book about him, Midnight (powerHouse,2003), Gottfried wrote about the times he became withdrawn. “He was often so far away he wouldn’t say a word for days.” She described Midnight’s life as caught in a “cycle” of illness, hospitalizations, imprisonment, and treatment.

“My thing is, I suffer from a disorder,” says Midnight. “Paranoid schizophrenic, chemical imbalance, with acute psychotic episodes, and she didn’t know that I had to be hospitalized. I get one of those every time I’m under pressure.” he adds, joking: “not right now.”

A guardian he calls Mommie Margaret raised Midnight and his sister. At 13, he ran away from home in Philadelphia to discover he could disappear into New York’s Times Square in the 1970s. “I had so many holes to crawl in and out of,” he says. He spent his teenage years living out of a locker in the Port Authority bus terminal, sleeping in movie theaters, hustling on the streets to survive.

“I used to dance at the Gaiety when I was underage.” The Gaiety Theatre on 46th street was a gay male burlesque show that opened in the mid-’70s and ran for almost 30 years. “I would come out, and they would play that song, babyface.” He starts singing, “Babyface…you got the cutest little babyface….no one could ever take your place.”

“They would play that, and I would have a big taffy with spiral colors on it, and I would suck on it and use it as a prop. It was a few bucks here and there. It was a different New York.”

Later on, he began using drugs which worsened his mental illness. “I remember I used angel dust, and it brought on my schizophrenia,” he recalls.

Midnight drifted in and out of Gottfried’s life in his twenties, running away on cross country trips. She often found him hospitalized, arrested, or living on the streets for long stretches, yet Gottfried remained a loyal friend who always tried to help get him back on his feet. She described it as an “exhausting commitment” at times.

Gottfried focused her entire career on the subject matter close to her heart – the disappearing communities and people of New York City that were suffering from poverty and being erased by gentrification. She preserved New York history from the seventies till her 2017 death in her books; The Eternal Light, Midnight, Sometimes Overwhelming, Bacalaitos and Fireworks and her final book, Mommie.

The books Mommie and Midnight are similar in their use of accumulated portraits, taken over long periods of time, focused on one subject.

In Mommie, she recounts the story of Midnight. “I never thought I had a project there,” she says about the process of making the book. After showing him the work one night on a slide projector, she remembered, “He just stood up from the table, and he reached out and shook my hand. He didn’t say anything. It let me know he was touched, and he got it.”

Midnight resurfaced after the book came out from time to time, remaining close till Gottfried succumbed to a long battle with breast cancer.

Flipping through the book with Midnight today, he nods at each page, affirming Arlene’s selections. “This is a good picture,” he says over and over. He recounts good times on birthdays at the Palladium and parties on New Year’s Eve, his favorite suits and hats. He gives liner notes like, “That’s my derby. That’s when you know you’ve won the hat race.”

His stories reveal the nature of their collaboration: a delicate balance between what he shows and what she records. “She didn’t want me to pose for any pictures. Just stay natural.”

“I was always trying to look tough.”

He harks to being in drug therapy in the 1970s. “They wanted me to break my image. They felt I had the image of a tough guy.” Looking at a nude of himself in a ballerina tutu, he says, “I didn’t do it till I met Arlene. I appreciate that picture.”

Midnight (powerHouse), published in 2003, is reminiscent of works like Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency or Jim Goldberg’s Raised by Wolves, where documentary photos are conceptualized into an artbook, yet the soul of the work lies in the real lives depicted.

Over the years, Midnight remains the most elusive of Gottfried’s works, as a portrait of a man, model, lover, friend struggling to survive on the streets of New York with an invisible disease. The photographs reveal glimpses of his face in the unfathomable experience of mental breakdowns, delusions and withdrawal, balanced by tender moments of joy, beauty, and love.

Today, Midnight is living in New York City at a facility that cares for the mentally ill. He has the same handsome face, kind eyes, and sly sense of humor. Looking at a self-portrait of Arlene, he remembers their time with deep affection.

“It’s just half of a lifetime here,” he says with pride. The book is phenomenal, a quiet story with few words.”

He sees it as a collaboration between peers, two individual artists. “It was well performed by the artist and the model,” he says. “I was challenging my own self-image—saying, ‘here I am. This is what God made.’ I want to share myself with everyone.”

Midnight is on view at Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York City till March 5, 2022

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com