It’s far from breaking news that Kanye West is a mama’s boy. Long before his debut album, The College Dropout, West wrote a song to his mother, Donda, entitled “Hey Mama,” which he premiered on The Oprah Winfrey Show in 2005. Last year, West named his 10th studio album Donda, released 14 years after his mother’s unexpected and tragic death. It included clips of her speeches and a mournful 50-second a capella chant of her name.

While Kanye has sung and spoken plenty about Donda over the years, their relationship has perhaps never been chronicled with as much clarity and emotional resonance as it is in Jeen-Yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy, a docuseries about West that arrives on Netflix on Feb. 16. (Jeen-Yuhs is produced by TIME Studios, the film and television division of TIME.) The docuseries reveals many aspects of West’s career: his shattering of early ’00s hip-hop conventions; his perseverance following a devastating car crash; his recent political ambitions. But above all, Jeen-Yuhs shows how Donda West deeply shaped each of those facets of Kanye’s life and many more, serving as the driving force behind his creativity, spirituality, self-confidence, and ambition.

Here’s how Donda West impacted her son and the world, as seen in the documentary and elsewhere.

Read more: The Inside Story Behind the Kanye Docuseries Two Decades in the Making

Nurturing Creativity

Donda grew up in Oklahoma City, the daughter of Portwood Williams, a shoe shiner and cotton picker who soon worked his way up to become an upholstery businessman in the segregated city. (“My mama was raised in the era when / clean water was only served to the fairer skin,” West raps on “New Slaves.”) In the 1950s, Portwood took Donda and her brother to some of the first U.S. lunch counter sit-ins to protest segregation, instilling in them the importance of fighting for justice and equality.

In 1973, Donda married the photographer Ray West in Atlanta; Kanye was born four years later. But when Kanye was a toddler, Ray began drifting away, showing more interest in his career than his family, according to Donda. The couple divorced in 1980, with Donda and Kanye moving to Chicago. “I often say that we had a great marriage and a great divorce,” Donda wrote in her 2007 memoir, Raising Kanye.

In Chicago, Donda became a faculty member at Chicago State University. She and Kanye moved houses frequently, with the young Kanye alternately pushing Donda towards and away from her romantic interests. (“You never put no man over me / And I love you for that, mommy, can’t you see?” he rapped on “Hey Mama.”) Kanye’s artistic talent was obvious early on—he won local talent shows on a perennial basis—as was his penchant for rejecting the status quo. He would purposely color fruit the wrong color to challenge perceptions: purple bananas, blue oranges. Donda looked at these transgressions with amusement and approval: “I never criticized him for it. I figured I would just nurture the creativity,” she wrote.

Donda and Kanye spent about eight years at a house on South Shore and 78th, where Jeen-Yuhs filmmaker Coodie Simmons captured them sitting on the stoops and reminiscing about that era. In a prescient twist, their family dog’s name was “Genius.” Kanye marveled about how small the house looked to him now, joking that he could touch both walls of his room by spreading his arms. Last year, Kanye built a replica of the house for his Donda listening event at Soldier Field in Chicago.

Kanye’s Biggest Champion

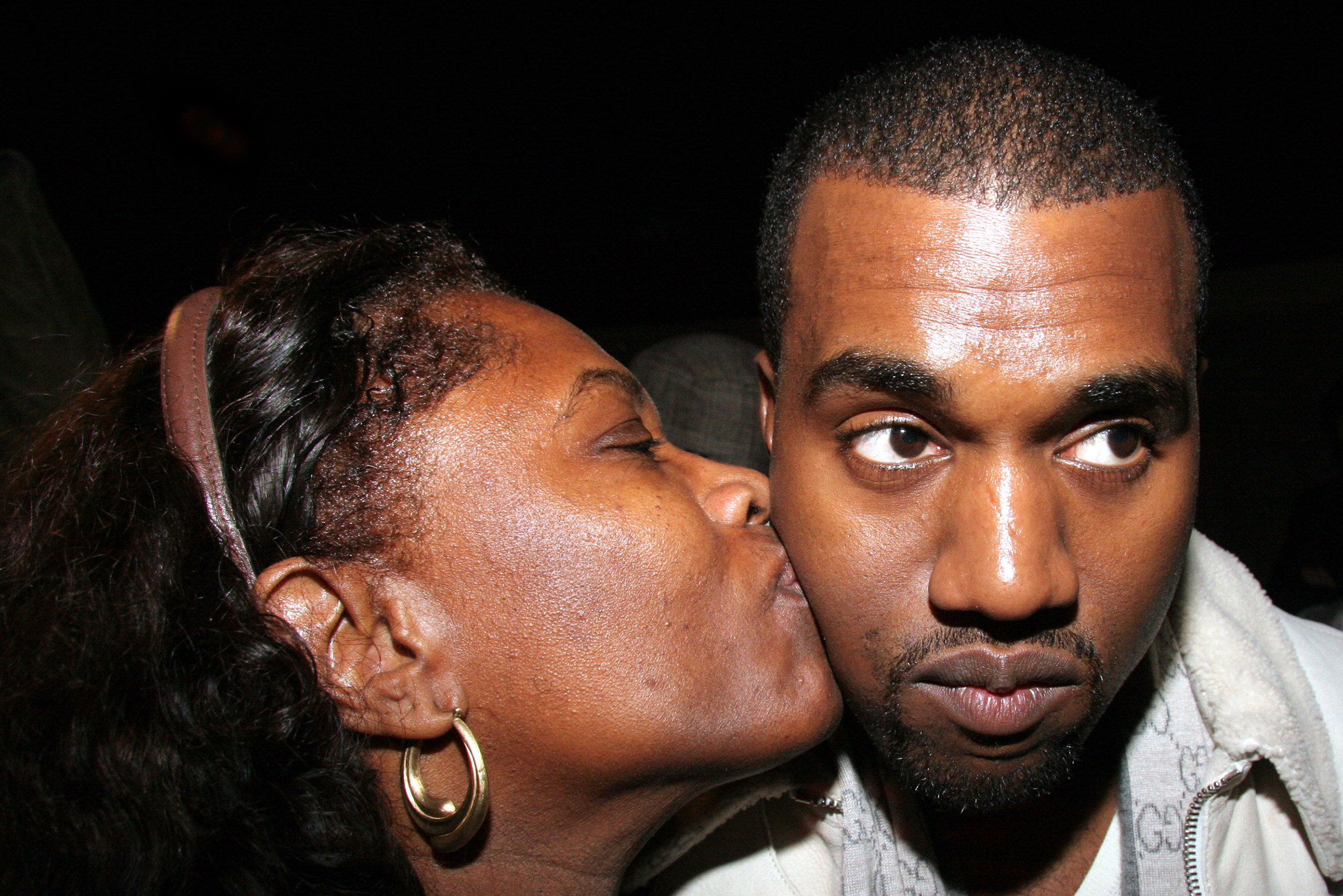

When Kanye started rapping as a teenager, Donda was his biggest booster. This is evident in Jeen-Yuhs when Donda, unprompted, starts performing one of Kanye’s earliest high school raps, which starts out, “It’s cool to be known for my rapping ability.” She tells her son that he plays “tracks like Micheal Jordan shoots free throws,” and in part three, enthusiastically raps all of “Hey Mama,” alongside him, beaming ear-to-ear.

Long before Kanye was rankling the public with what many deemed arrogance, Donda was happily nurturing this healthy self-esteem, believing it to be one of the keys toward success. “I didn’t sit down and tell him, ‘You have to be the best.’ I just always thought he was,” she explains in Raising Kanye. “This, I believe, bolstered his confidence and his enthusiasm in all that he did … arrogance is in the eye of the beholder.”

Donda’s support was far more than only emotional. When Kanye was 14, Donda gave him a Christmas gift of $1,000, which he used to buy a new keyboard. He was soon making booming beats in their house day and night. Donda also helped him forge two crucial connections: to the producer No I.D., whose mother worked alongside Donda at Chicago State University; and to the producer Doug Infinite, who was one of Donda’s former students. Both served as Kanye’s mentors to develop his production chops and sound.

“Moms are always like, ‘Here’s someone that you should help,’” No I.D. told Billboard in 2014. “I understood, checked it out, and it was him. He was just learning how to make music, but he was the most persistent person who I’ve ever met.”

Kanye soon outpaced both mentors and decided to move to Newark to be closer to hip-hop’s power center. Donda, of course, would accompany him on the long drive: “Me and my mama hopped in that U-Haul van,” he rapped in 2005’s “Touch the Sky.” Their journey from Chicago to Newark is also documented in Kanye’s song “Last Call,” in which Donda herself can be heard telling Kanye, “Kanye, baby, we’re here.”

A few years later, Simmons would capture Kanye getting into a spat with Doug Infinite when the latter felt slighted by Kanye in a news article. Kanye responded by telling a local radio station, “The only person I owe something is my mother.” And after Kanye laid down his first Roc-a-Fella performance, on the 2002 Jay-Z song “The Bounce,” he mumbled in the studio to no one in particular: “A long way from rapping at my mama’s house.”

Posthumous Impact

When Kanye became a pop supernova, he grew even closer to his mother. Donda became his manager; the chair of the Kanye West Foundation, which was later renamed the Donda West Foundation; and the CEO of Super Good, the parent company of Kanye West Enterprises. Ironically, before “good” became a key word in Kanye’s lexicon, serving as the name for his label G.O.O.D. Music, Jeen-Yuhs shows Kanye ribbing Donda when she uses the word “good,” telling her that the word is “so old.”

In 2007, Donda died following complications from liposuction and breast-reduction surgery. Kanye’s grief has plagued him for years, manifesting in songs and interviews, most wrenchingly in 2008’s “Pinocchio Story,” which paints his public rise as entwined with Donda’s death. In 2015, he told Q Magazine that he still blamed himself for her death: “If I had never moved to L.A. she’d be alive. I don’t want to go far into it because it will bring me to tears,” he said.

In 2013, Kanye wrote the hymn-like “Only One” from her perspective, saying the song’s lyrics came to him in a quasi-fugue state as if she was speaking directly to him. The album Donda is filled with references to her and clips of her voice, including her reading of the essay “Who Am I” by Marya Mannes. On “Jesus Lord,” Kanye sings: “Mama, you was the life of the party … When you lost your life, it took the life out the party.”

Donda’s liveliness is more than evident in Jeen-Yuhs. She overflows with exuberance and pride after Kanye’s performance on Def Poetry Jam. And in one of Jeen-Yuhs’ most powerful scenes, she teaches Kanye a lesson about humility: “The giant looks in the mirror and sees nothing,” she tells him, as he looks at her wide-eyed. “I think the way you are is really just perfect. But at the same time, remember to stay on the ground. You can be in the air at the same time.”

That footage was almost never released: Simmons, in an interview with TIME, said he forgot the clip existed for more than a decade and accidentally stumbled across it during the Trump era. “It was almost like that footage just appeared from Mama West for me to send to Kanye,” he says. “I sent him an email, with the subject line: ‘Your mother wanted me to send you this.’ It took him a minute to respond, but he FaceTimed me and was like, ‘I never would have thought in a million years she said that.’”

jeen-yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy premieres on Netflix beginning Feb. 16. Twenty-four years in the making, this documentary about Kanye West was directed by Coodie & Chike, from TIME Studios and Creative Control.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com