On Tuesday tech giant Microsoft announced its proposed purchase of gaming company Activision Blizzard for nearly $69 billion. The deal would grant Microsoft ownership over globally recognized franchises like Call of Duty, World of Warcraft, and Candy Crush, to name a few. It also creates a new division in the company, Microsoft Gaming, to be led by the company’s head of its Xbox division, Phil Spencer.

For Activision Blizzard, this couldn’t have come at a better time. The company, run by CEO Bobby Kotick since 1991, has been the subject of scrutiny and lawsuits based on numerous allegations of discrimination, sexual harassment, and a toxic workplace culture at the company. Incidents ranging from drinking on the job to multiple instances of sexual assault are said to have occurred under Kotick’s watch. Kotick was allegedly aware of at least some of these allegations, and was subpoenaed by the Securities and Exchanges Commission in September of 2021.

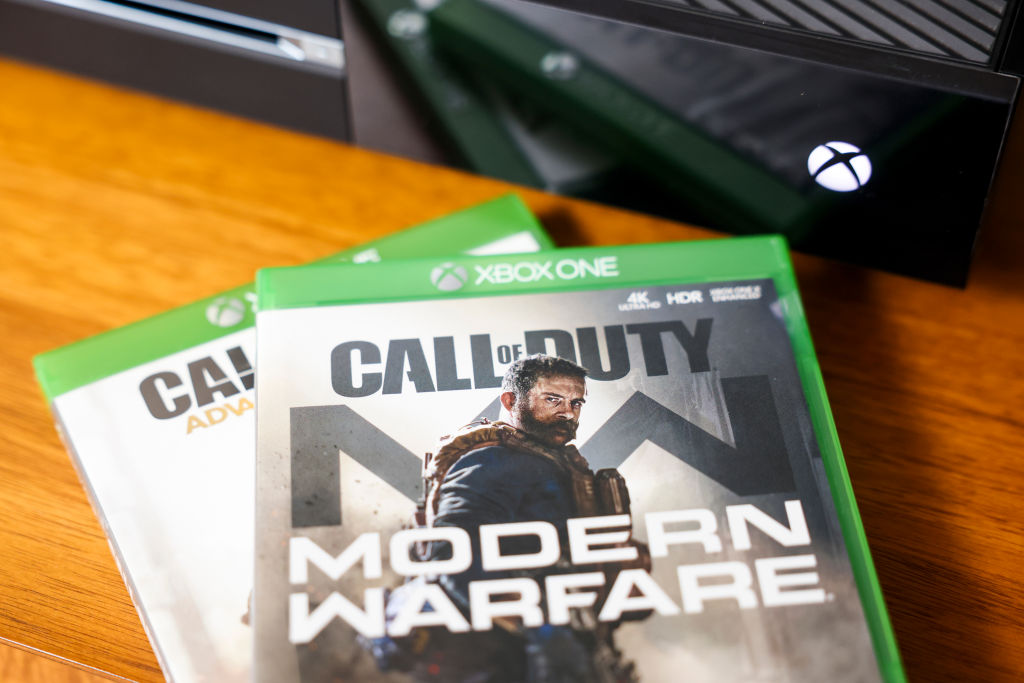

“Until this transaction closes, Activision Blizzard and Microsoft Gaming will continue to operate independently,” said Phil Spencer in a post explaining the future change in leadership. “Once the deal is complete, the Activision Blizzard business will report to me as CEO, Microsoft Gaming.” In the post, Spencer included an image of an organizational chart of the new Microsoft Gaming division, with Kotick nowhere to be found. Spencer also said the behavior described in the Activision Blizzard accusations have “no place” in the gaming industry in an email to his staff. Despite the bad press, Activision Blizzard is one of the most successful game companies around, pulling in $8.1 billion in revenue in 2020 primarily due to franchises like Call of Duty and World of Warcraft.

The purchase also brings into the Microsoft fold close to an extra 400 million monthly active players, giving its subscription service, Game Pass, a potentially huge boost. The Netflix-but-for-games service grew dramatically since its launch in 2017, and added over a dozen games to its lineup after its acquisition of the gaming giant Bethesda in 2021. That buy sent the service from 18 million users in 2021 to over 25 million users as of January 2022.

Like Bethesda, whose hit game The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim is one of the best-selling games of all time, Activision Blizzard has games with some seriously broad appeal. Both Call of Duty: Vanguard and Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War were among the best-selling games of 2021 globally, and the player base of the online role-playing game World of Warcraft continued to grow over the year.

More from TIME

Microsoft buying a studio that makes games for multiple platforms could mean trouble for gamers uninterested in Microsoft’s Xbox platform. Games like Skyrim were successful due to multiple releases on a variety of platforms like the PC, Xbox 360, and PlayStation 3. Since then, the 10-year-old title has been brought to every major platform, including the Nintendo Switch. An acquisition from a company like Microsoft could likely mean a sequel would be only available to Xbox users, mobile devices, or PC gamers using Windows, leaving out players using Sony and Nintendo consoles.

“Activision Blizzard games are enjoyed on a variety of platforms and we plan to continue to support those communities moving forward,” said Spencer in his announcement post. For Microsoft, playing nice with its competition is the fiscally responsible move, and selling games individually on platforms that won’t allow its streaming service (like Apple’s iOS or Sony’s PlayStation) is one way to extract a bit of value from the competition. Still, some competitors, like Sony, have shown themselves not keen to play ball, and have charged developers like Fortnite’s Epic Games to connect players on its PlayStation consoles to those on other platforms in multiplayer games.

What’s concerning is what developers might have to do to make their independent titles more appealing to the companies that are increasingly fewer and farther between. “If we have to adjust what we’re doing to meet those platforms in order to survive, I feel like at that point, we’re all better off just getting jobs at those companies,” says Brandon Sheffield, director of independent studio Necrosoft. For Sheffield, who co-founded the company ten years ago, major success hasn’t exactly kept them afloat: deals with a variety of platforms have. Necrosoft’s journey was mostly funded by investments from companies looking to boost the number of titles in their catalog on new platforms. “Our last chunk of money that we got was from Google Stadia because they needed stuff there,” says Sheffield.

Platforms like indie-friendly game marketplace Itch.io make supporting small independent studios (or solo game developers) possible, but it also requires consumers to actually buy individual titles, rather than the all you can eat buffet Microsoft streaming serves its audience. And as tastes change, and companies further pour resources into games that can continue to generate revenue or maintain a thriving online community, it leaves independent developers struggling to figure out which direction to go in order to find success. With Microsoft building its stable of in-house games behind a subscription fee, why bother funding outside independent projects?

“I just worry we’re trending in a direction that is less friendly toward innovation,” says Sheffield, concerned about an acquisition like this sucking all the oxygen out the room for smaller developers that don’t have the backing of larger studios or publishers who are no longer interested in promoting indie titles. “I don’t want us all working for the same three companies and making the same kinds of games, or different shades or flavors of the same games.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Patrick Lucas Austin at patrick.austin@time.com