In its edible form, salt is used to dry out meat; in its mineral form, it’s used to dry out snowy highways; and in its tax form, SALT—the acronym for state and local tax deductions that disproportionately benefit well-heeled taxpayers—might sound like a topic bound to dry out conversations.

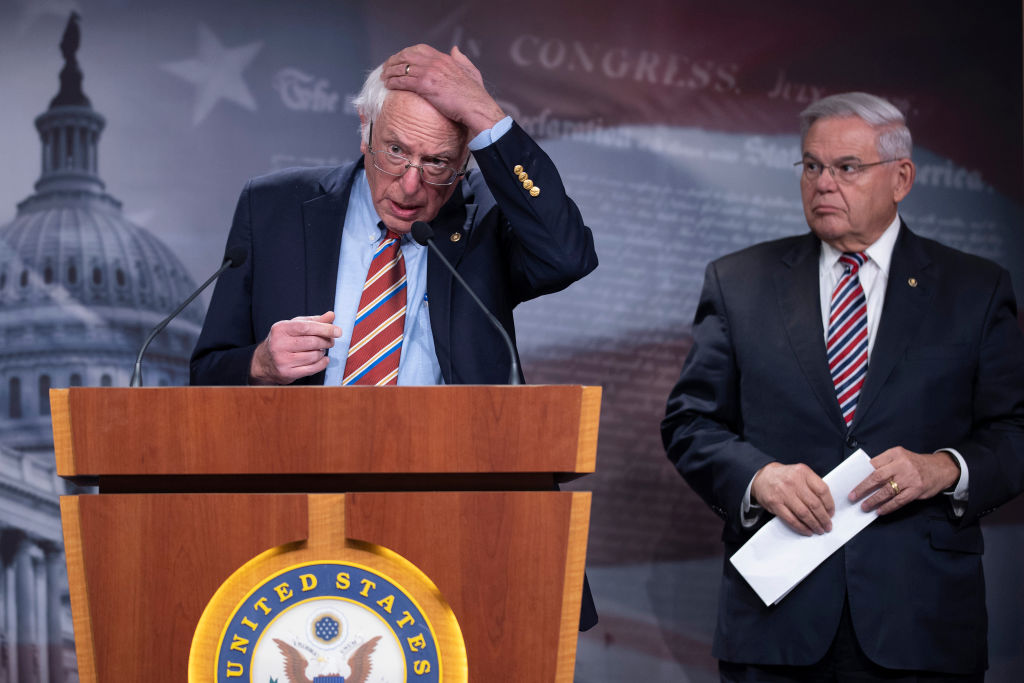

Even Sen. Bernie Sanders, a key player on negotiations concerning the SALT cap in the Democrats’ flagship $1.7 trillion social spending and climate Build Back Better (BBB) package, quipped that SALT does not excite most people on the Hill. “I thought she was the only person in the world who was concerned about SALT,” he told me, gesturing to another reporter, when I asked him for an update on SALT’s status.

But don’t be fooled. As Senate Democrats struggle to pass BBB, the debate over SALT may be one of the more interesting things happening at the Capitol. Whatever form the provision ends up taking could have major financial implications for taxpayers in high-tax states; huge electoral consequences for the Democrats who represent those states; and significant political fall-out for the party’s make-the-rich-pay-their-fair-share political messaging.

That’s because raising the cap on SALT deductions from $10,000 to $80,000, as prescribed in the House-passed version of BBB, would disproportionately help taxpayers rich enough to benefit from itemizing their federal tax deductions—which is to say, the richest fifth of Americans. According to a November analysis from the nonpartisan Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, the higher SALT cap would primarily benefit the richest 20% of taxpayers, and three-fourths of the benefits would go to the richest 5%.

Democrats are split over what to do about it. Some Democrats, like Sen. Bob Menendez and Rep. Tom Suozzi, who recently announced a run for New York Governor, support raising the cap on SALT deductions as a means to reverse the effect of Trump’s 2017 tax bill, which led to tax hikes in blue states. Others, like Rep. Jared Golden, argue against including raising the cap on the grounds that it paints the Democratic party as hypocrites. If they raise the SALT cap, the second-most expensive item in a bill designed to bolster American working families would be a tax break for coastal elites.

The standoff leaves Democrats in a damned-if-they-do, damned-if-they-don’t bind: deliver a windfall to wealthy Americans or screw over Democratic states on the eve of a midterm election where Democrats’ narrow majorities in both chambers are at risk.

The tricky politics of raising the SALT cap—or not

Republicans created the $10,000 cap on SALT deductions as a means to offset the cost of their other tax cuts in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). The TCJA reduced the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21% and decreased individual tax rates across the board. Because the TCJA nearly doubled the standard deductible, the main losers of the new $10,000 SALT deduction cap were well-to-do people in states with the highest property taxes—Democratic states, like California, New York and New Jersey.

Republicans argued that the federal government should not subsidize the progressive benefits that coastal blue states offer by allowing the states’ residents to deduct their higher SALT liabilities from their federal taxes. “My 29 million constituents in Texas are not interested in subsidizing bad governing decisions made in places like New York or San Francisco, and they shouldn’t have to,” Sen. John Cornyn, a Texas Republican, said at a December press conference.

Democrats in favor of raising the SALT cap argue that allowing taxpayers to deduct more state taxes isn’t a gift just for the rich. It’s a gift for middle-class wage-earners, like teachers or firefighters, who might have relatively high combined household incomes—say $200,000—but see much of their earnings wiped out by high costs of living in big metropolitan centers. The median home price in Hoboken, New Jersey is $749,000, for example, while the median price in Cheyenne, Wyoming is $340,000. “Our cost of living is higher here, so our folks need to make more. They shouldn’t be punished and double taxed for it,” Rep. Josh Gottheimer, a New Jersey Democrat who refused to vote on the House’s version of BBB without a higher SALT cap, said earlier this month.

More from TIME

Some Democrats also say that failing to raise the SALT cap may hamstring the progressive movement. Their argument? The TCJA’s low cap could have the effect of driving high taxpayers out of high-tax states, which would reduce blue states’ revenue and, in turn, gut their ability to provide robust social policies, like tax credits for electric vehicles, and city and state-run universal pre-k and paid family leave programs. A higher SALT cap enables coastal blue states to be “laboratories for democracy” where progressive policies can be tested before they become federal law, one Democratic aides, granted anonymity to discuss sensitive negotiations, told TIME.

But raising the SALT cap comes with a hefty price tag: $275 billion over five years, according to the hawkish Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. That cost, some Democrats argue, is egregious considering that lawmakers already scrapped (free community college) or watered down (paid family leave) a slew of progressive policies in order to make the bill’s cost projection more appealing to centrist Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema.

“Our priorities should be making sure that families have affordable childcare, our priority should be making sure that we have paid family and medical leave and that it’s meaningful,” Sen. Michael Bennet, a Colorado Democrat also leading the negotiations, tells TIME. “To the extent that we’re spending money on a regressive tax policy, like SALT, I think that does diminish our ability to do those other things.”

No matter how you cut it, the politics of the SALT debate aren’t good for Democrats. Those in favor of raising the cap must, essentially, defend their decision to include a tax break for the relatively well-off in a bill that is being sold—by the President of the United States, no less—as a tool to bolster the middle class. The argument leaves them wide open to attacks from the GOP, and Republicans are taking their cue. With TCJA, “our Democrat colleagues railed against us,” Republican Sen. Pat Toomey, ranking member of the Senate Banking Committee, told TIME. “Now, with the first chance they get, they do this huge tax giveaway to their wealthiest supporters.”

But Democrats against raising the cap must grapple with the fact that it leaves many of their colleagues especially vulnerable in 2022. East Coast House Democrats like Reps. Tom Malinowski and Mikie Sherrill of New Jersey campaigned in their 2018 elections to repeal the low SALT cap. Failing to deliver on that by the 2022 midterms could put their swing district seats at risk.

A slow-motion debate

Weary of under- or over-SALTing their preeminent policy package, the caucus has yet to agree on the tax measure, and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer’s goal of voting before Christmas becomes less and less likely by the day. The updated draft of the bill that Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden released Saturday contained no language on the SALT provision, instead reading: “PLACEHOLDER FOR COMPROMISE ON DEDUCTION FOR STATE AND LOCAL TAXES” under the SALT subhead.

Sens. Menendez of New Jersey and Sanders of Vermont are among those trying to hash out an agreement that eases the tax burden on middle class families without providing a boon to the richest 1% of Americans. One idea is to eliminate the House-proposed $80,000 SALT cap entirely, and instead phase out the ability to take advantage of SALT deductions by limiting it to taxpayers under a yet-to-be-determined income threshold. Menendez and Sanders are currently considering maximum incomes of somewhere between $400,000 and $550,000 for single-filers per year, a Democratic aide says. Sanders prefers a figure closer to the former while Menendez has pushed for something closer to the latter, the aide adds, noting that cost of living is higher in much of New Jersey than in Vermont.

Whatever the final cap, the ongoing debate is feeding Republican fodder that Democrats are at odds with one another, and with their own priorities. “It sounds like they’re conflicted,” Cornyn joked to TIME on Tuesday.

It may be one the few occasions he and Bennet come close to agreement on something.

“The [expanded] child tax credit [costs] $190 [billion] versus $275 billion for SALT,” says Bennet. “I do think that it raises the question about what our priorities really are.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Abby Vesoulis at abby.vesoulis@time.com