If Maria Ressa long has been known to people who follow the news, she has become absolutely essential to anyone grappling with why the news has gotten harder and harder to follow.

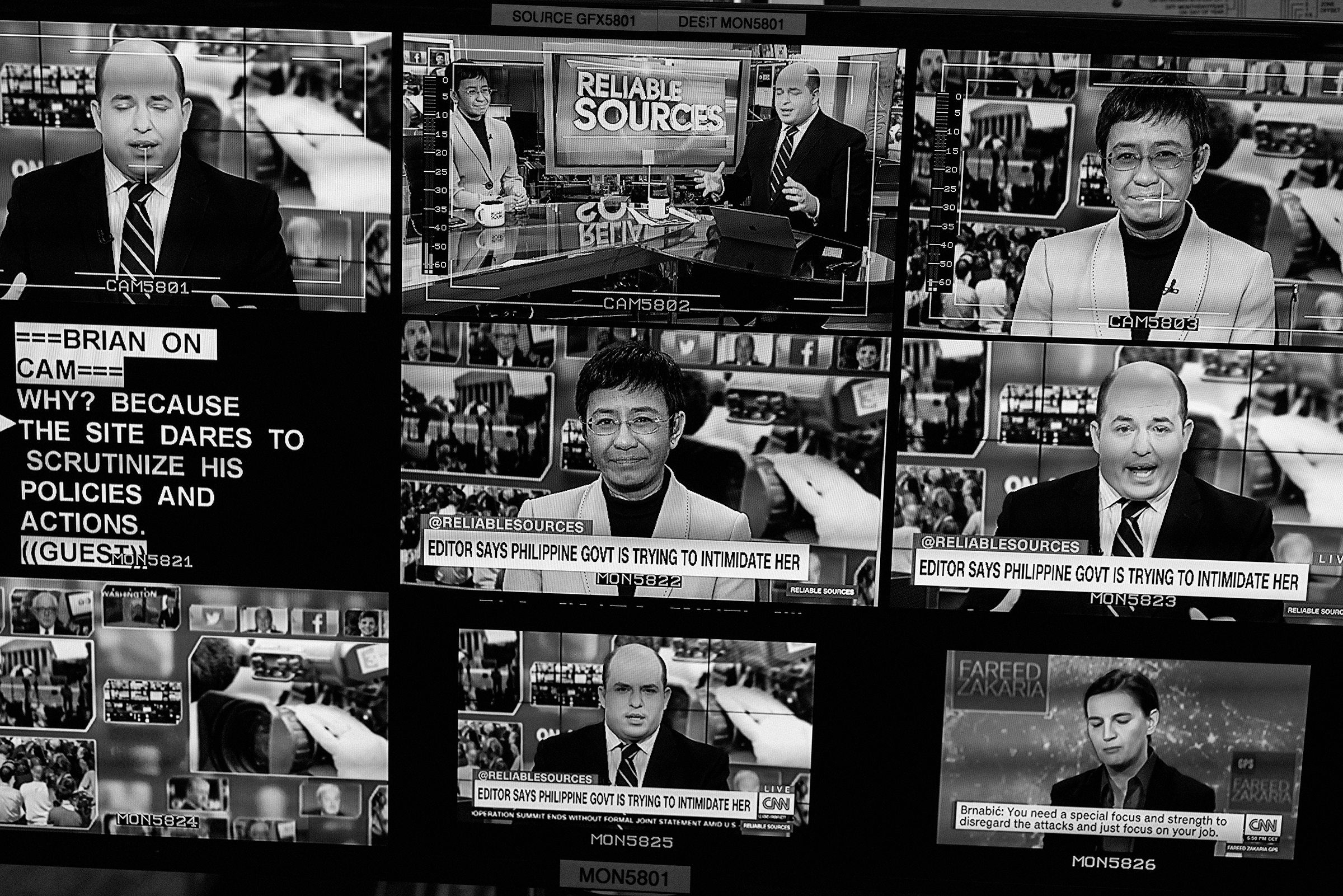

Born in Manila and raised in New Jersey, Ressa, who is 58, worked for CNN for years, then in 2012 co-founded Rappler, a vibrant online news site in the Philippines. Four years later an incendiary populist named Rodrigo Duterte was elected President of a country where, a practical matter, Facebook is the Internet. Rappler exposed the hidden hand of his supporters in viral posts, trolls and malign disinformation, as well as the feebleness of Facebook’s efforts to police itself. Since then Ressa has lived at the dangerous intersection of despotism and social media. Arrested, threatened and harassed online, in 2018 she was named a TIME Person of the Year under the heading, “The Guardians and the War on Truth.”

And now Ressa has been awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace, along with Dmitry Muratov, a founder of Novaya Gazeta, an independent Russian newspaper at which six reporters have been murdered. A few hours after getting the news from Oslo, Ressa spoke to TIME by phone from Manila. Her new book, How to Stand Up to a Dictator: The Fight for Our Future, is slated for publication in April.

Congratulations. What do you think the impact will be of this? When TIME named you a Person of the Year in 2018, you talked about its practical effect in protecting you and your work.

It was a shield. It acted like a shield. And it actually helped us survive because that was December 2018, and my arrests began like two or three months later, and it was going to get worse. Imagine if you hadn’t done that.

That was also when I realized that the only defense we have is to shine the light. And you had given us more battery power, a global megaphone. And that gave us breathing space to keep doing our jobs. It could have been much worse, I think, without.

So what does the Nobel Peace Prize do?

Oh, my gosh, I can’t quite fathom yet. I shouldn’t say this, but I thought it would be [Alexei] Navalny. But it does make sense. The statement they made is exactly the same reason why you did the Guardians in 2018. The platforms that deliver the news are biased against news. And we are being insidiously manipulated. All of that is breaking down trust. Journalists are the target of this.

Read More: Maria Ressa: We Can’t Let the Virus Infect Democracy

It’s like we bought into a digital landscape that commoditizes news. So the real news that we do, which takes time and money, is placed in the same setting as the gossip down the street. And the gossip always wins. So it is sugar and vegetables.

This made me realize that it is existential. It is a battle for facts. And we’re at the front line, and it has gotten far more dangerous than it has been in the past. I think that also shows the role of the journalists in fixing this and fixing the mess that we’re in right now.

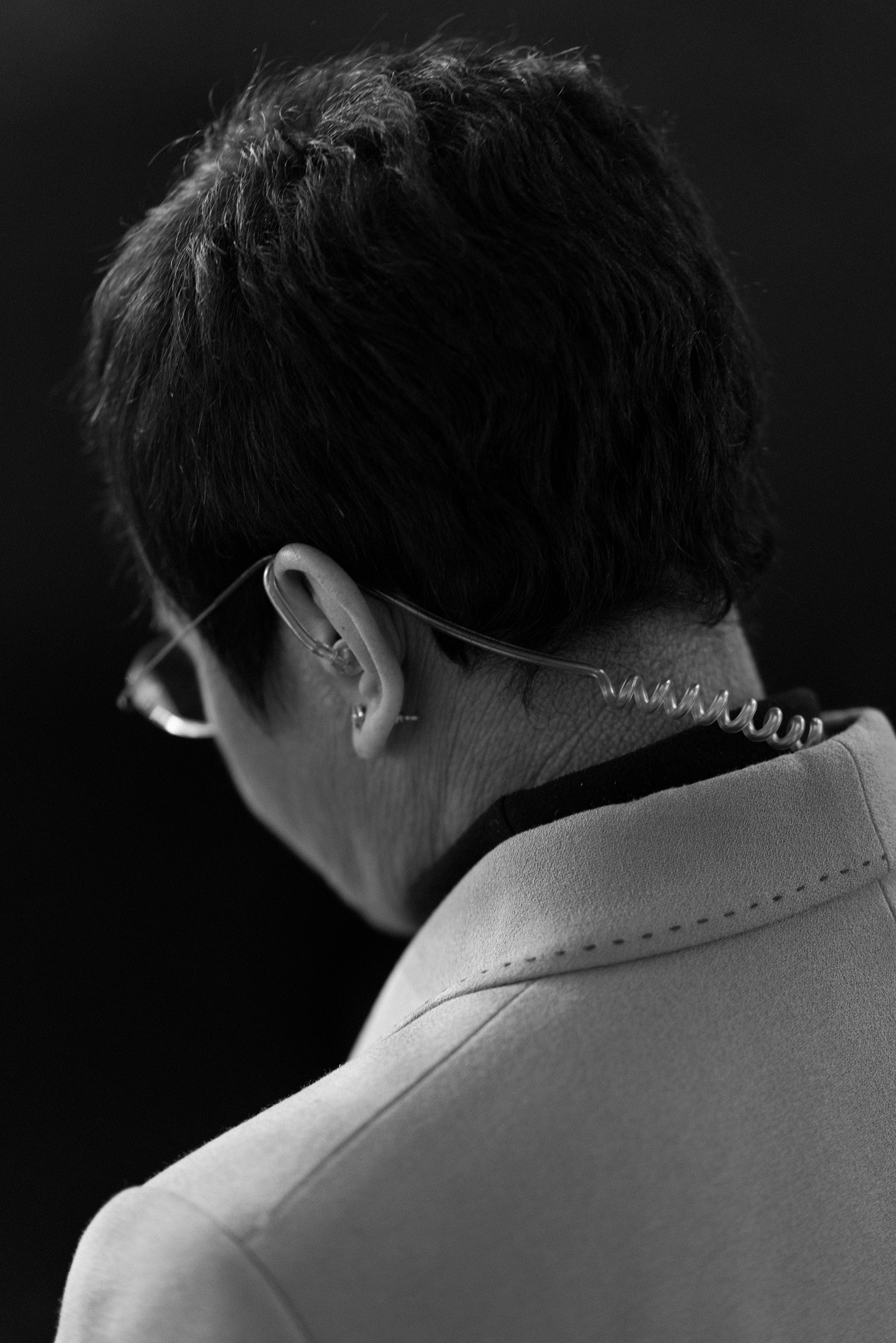

Where were you when you heard?

I was live in a panel of the independent news groups in Southeast Asia, and they had just come from watching A Thousand Cuts [the Frontline documentary on Ressa]. So we were talking about the survival of independent media in Southeast Asia, and how do we move forward? Right. And in the middle of that, I get a call. And I mean, it just said “Norway.” My God.

I said, “Hold on a second,” and muted and I took the call. And then of course when it was announced, I went from kind of stunned disbelief to like–when I started to talk about why journalism is important, and what we had gone through, that’s when I teared up.

It comes at this strange time for me and Rappler. January is our 10th anniversary. And this shows me exactly how much the world of news has changed since the time we created Rappler, which was about building communities of action, which was built on social media, with the optimism of this technology that could help jump-start development, the dreams that we had. And it worked. It did work all the way until 2016. And then the nightmare. We saw that nightmare. We were plunged into it first. [The populist Rodrigo Duterte became President of the Philippines in June, four months before Donald Trump was elected in the U.S.]

It just shows the role that journalists play because it goes back to without facts, you can’t have truth. Without truth, you can’t have trust. How can you have democracy without that? This is the fabric that holds us together: the shared reality.

Read More: Maria Ressa Is on the 2019 TIME 100 List

I hope that it will give energy at home. Because this is the week where Filipino candidates announce what positions they’re running for. And Bongbong Marcos said he would run for the presidency. And the opposition leader said she would run. So here we are. Think about this: 35 years after the Marcos family was chased out of the Philippines by People Power, the son comes back and is going to run for president. In 2019, we exposed the disinformation networks of Marcos, which even more extensive than Duterte’s. He started his in 2015. And it’s on YouTube, it’s Facebook. How do you change history? You do it through social media. You do it by seeding metadata. It is death by a thousand cuts. It’s historical denialism. We have a lot at stake in the May elections and American social media platforms will play a role in whether we will have integrity of elections.

Have you met your co-winner, Dmitry Muratov?

No, we haven’t. But I do know the organization.

So this was already a bad week for Facebook. In 2019 you wrote for TIME, the headline was “Facebook Let My Government Target Me. Here’s Why I Still Work With Them.” Is that still where you are?

What changed is I’m also part of the Real Facebook Oversight Board. And yes, we’re still one of two Filipino fact-checking partners of Facebook in the Philippines. But I’m also far more frontal. I think the shift for me happened when I started writing my first book [Seeds of Terror]. I was looking at radicalization, the way the virulent ideology that powered al Qaeda was being transmitted. Like, how were people going to become suicide bombers? So I was looking at information cascades and an individual, the hijacker from 911, behaves very differently when they’re in a group where peer pressure comes in. So this is like the Solomon Asch experiment. Are you familiar with that?

No.

Solomon Asch had this experiment where you have three lines, and there’s six people around the table. The sixth person is the one who is the test case, the five people are actors. And he asked: Name the shortest line, A, B or C. The shortest line is in fact A, and the longest line is C. The five people go before the test subject and name the longest line as the shortest line. And 75% of test subjects will follow the group–75% said the longest line is shortest line despite what their eyes show them.

So the group is different. And when you’re talking social networks and scale, the group exerts pressure on the individual and emergent behavior creates behavior. Which is what social media is doing now. Violence, anger, disinformation is what pumps through this. That’s kind of what Francis Haugen has shown us.

While the Senate is focused on Instagram and the impact on teenagers, what about the impact on journalists? We are being distributed on the same platform that is now being used by autocrats and dictators to actually change behavior with microtargeting. It happens in the dark. I’m much more adamant about legislation. I’ve done the Forum on Democracy and Information. We came out in November last year with 12 structural solutions, 250 tactical ones. I was co-chair with Marietje Schaake. And people like Chris Wiley and Roger McNamee were on it, some of the same people that we also dragged into the Real Facebook Oversight Board.

Since the “cyberlibel” conviction last year, you’ve had to stop traveling abroad. Will you be able to go to Oslo in December?

It’s not a final conviction. But I’ve had four requests that have been turned down. Last December, my mom was diagnosed with cancer, she had a mastectomy and I wanted to be there and court denied it at the last minute. I will put in for travel to Oslo, and I will fight for my right to travel.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com