Over the years, a number of Disney’s theme park attractions have served as inspiration for films: The Country Bears (2002), The Haunted Mansion (2003) and, most notably, the Pirates of the Caribbean series. Jungle Cruise is the latest addition to this sub-genre. Directed by Jaume Collet-Serra, the film—released in theaters and on Disney+ with Premier Access on July 30, and topping the weekend box office with $90M globally, which factors in over $30M on streaming—is based on the ride of the same name. Jungle Cruise was on Disneyland’s roster when the theme park opened in 1955, and has since become an iconic attraction, operating at Disney theme parks in Orlando, Tokyo and Hong Kong in addition to the original Anaheim location.

But the popular ride has long faced criticism for its racist portrayal of Indigenous peoples. In January 2021, Imagineering—the arm of Disney that creates and constructs its theme parks—announced that it would be updating the 66-year-old ride to address “negative depictions of natives.” In July, two weeks before the film’s release, Disney shared that it was reopening the revamped attraction.

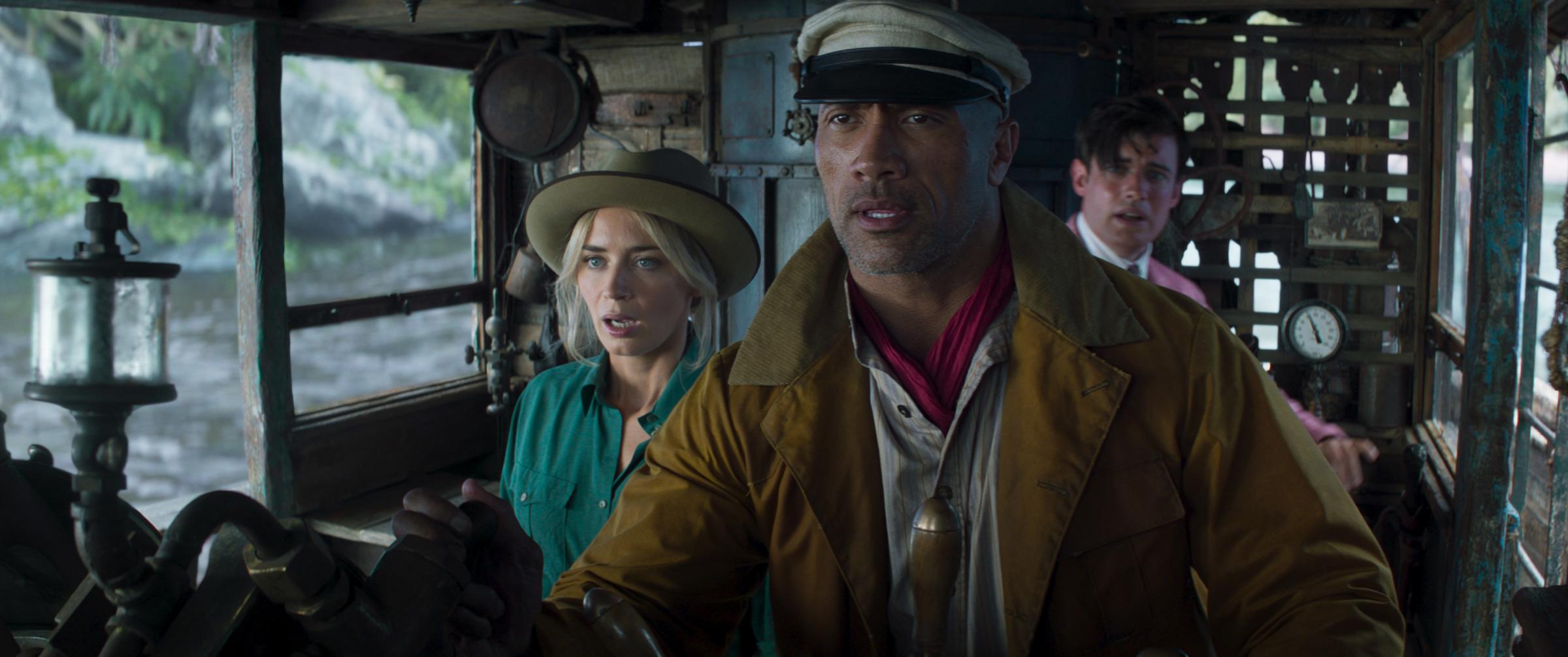

On the ride, visitors to the Jungle Cruise journey on boats through major rivers of the world, from the Amazon to the Nile, as animatronic characters emerge from corners of the jungle. A skipper, who keeps guests entertained with dad jokes and corny puns, serves as a guide. The film also ventures into the Amazon jungle, with Dwayne Johnson playing the skipper, Frank Wolff. Set in 1916, Jungle Cruise follows British botanist Dr. Lily Houghton (Emily Blunt) as she enlists Frank’s help to explore the jungle to find the Tree of Life, which is fabled to have healing powers and which she hopes will revolutionize the field of medicine.

Plans for a movie based on the Jungle Cruise ride were in motion since at least 2004, and a script was already in development when Michael Green was brought on to write the screenplay in 2017. Green would complete the screenplay with Glenn Ficarra and John Requa. He tells TIME that the initial script had already sourced a lot of material from the ride, but that he saw an opportunity to incorporate more elements from the attraction. Green adds that Imagineers and Disney representatives were collaborating on renovations for the Jungle Cruise well before he joined the production team. “They were aware of things they wanted to improve on, and had far-reaching plans.”

While the Jungle Cruise movie draws inspiration from the ride, it also departs from aspects of it in significant ways, with the script finding opportunities to turn racially insensitive perceptions on their heads. Here’s what to know about the original ride, how the movie differs and what all of it means in the grand scheme of Indigenous representation in popular culture.

How the Jungle Cruise ride portrayed Indigenous characters

In the Jungle Cruise theme park attraction, Indigenous peoples appeared as headhunting tribesmen with spears in their hands—next to piles of human skulls—who guides warned were attacking passing boats. One character in particular who was portrayed as primitive and dangerous was Trader Sam, who carried shrunken heads and was known as the “head salesman.” “He has a great special for you all today: just two of his heads for one of yours,” a skipper would joke to tourists on the ride. Trader Sam was also referred to as a chef who opened a cannibalistic cafe. Another area of the jungle showed a “trapped safari” scene, where men were chased up a tree by surrounding animals, with a white explorer at the top of the trunk and dark-skinned native guides at the bottom, next to the horn of a rhinoceros.

In Disney’s recent refurbishment of the Jungle Cruise ride, these racist and stereotypical features were removed. The headhunting tribe is gone, Trader Sam is replaced with “Trader Sam’s gift shop” that includes a lost and found, and the trapped safari scene now features adventurers of varied racial backgrounds grabbing onto the tree. The changes were made at the theme park in Anaheim, and Disney has said the updates will be completed by this summer at Walt Disney World in Orlando.

“Oftentimes in these scenarios, if there is Indigenous representation, we’re depicted as the stereotypical savage, or uncivilized creature,” says Daisee Francour, the Director of Strategic Partnerships and Communications at Cultural Survival—a nonprofit that advocates Indigenous peoples’ rights and cultures—of the headhunters and Trader Sam. Francour is a citizen of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin and identifies as Haudenosaunee. “It’s very dehumanizing and we’re often not even seen as people, but we’re almost portrayed more as animalistic.”

The depiction of Indigenous peoples as “merciless Indian savages” can be traced back to the Declaration of Independence, which uses that exact phrase to describe Native Americans. “That dehumanization, which we see reflected here with this theme park, is rooted in the foundation of this country,” Francour says. “And because of that foundation, it shows up in this stigma in other ways.”

The dehumanized view of Indigenous peoples carries through much of American popular culture, seen commonly in Westerns and television series like Tarzan, says Cliff Matias, the Cultural Director of the Redhawk Native American Arts Council, a nonprofit dedicated to educating the public about Native American heritage. “It’s the same narrative of these homelands of Indigenous people being rescued from the savage people, and the humble, noble explorer being victimized,” Matias, who is Taíno and identifies as Latinx, says of the depiction of Indigenous peoples in the theme park. The narrative has always been flipped to show the “European mindset of, it’s the savages who attack,” Matias says. “Hollywood has always pretty much told that story through those eyes.”

Adapting a ride for the big screen

The Jungle Cruise movie loosely follows the theme park attraction’s storyline of early 20th century adventurers exploring the jungle, reimagining some of the ride’s characters for the film. Most notably, Trader Sam appears in Jungle Cruise, played by Veronica Falcón, as a woman who is a chieftain of the Puka Michuna tribe. Green describes her character as smart and savvy, someone “who was very much in control of herself and what happens to her and her tribe.” “That was a chance to take a familiar trope of the ride and bring it into the film in a new way,” Green says.

More broadly, the Puka Michuna tribe is portrayed with an approach that aims to subvert stereotypes about Indigenous peoples. In one of the film’s opening scenes, skipper Frank tells the tourists on his riverboat about the tribespeople who are the “deadliest hunters in the hemisphere.” The passengers are attacked by a crew with blow darts, before it becomes evident that Frank had staged the ambush to add some thrills to his tour. “What we felt we could still play with is a lot of false preconceived notions,” Green says of the scene. “At the time when this film takes place, a lot of people coming from where those tourists were coming might think of those natives as backwards tribes. And we could instead be poking fun at people’s expectations of it.”

These tourists only see a glimpse of the Pika Michuna tribe while on the cruise, and are missing the “sophisticated, rich, dignified lives” of the Indigenous people, Green says. He and the team hoped to portray the local inhabitants in a more well-rounded way. “We wanted to give everyone in the film the dignity they deserve,” Green says. “If you set something in a place you want the people to be represented correctly and you want them to speak the correct languages.”

According to Disney’s press notes, the filmmakers researched the Tupi language that was widely spoken in Brazil and created their version of the language for the film’s characters. They also wanted to accurately emulate what the Amazon jungle looked like in the early 1900s, and studied the animals and flora of the time. Director Collet-Serra spoke of a cultural advisor that the team worked with to aim for proper representation.

While these efforts brought necessary changes to the film adaptation, some viewers have commented on the mixed messages conveyed by the portrayal of Indigenous characters. In NPR’s Pop Culture Happy Hour, Native American journalist Vincent Schilling gave a nod to Disney casting Johnson, who is Samoan, as the lead character. But Schilling also discussed a scene in which Trader Sam referred to the tribe’s clothing as “ridiculous costumes.” “I feel as though Jungle Cruise did a valiant effort in trying to represent Brazilian Amazonian tribes in a certain way that was actually fairly legitimate,” Schilling said, which was why the chieftain’s description stuck out. “You’re trying to be authentic. So is it ridiculous, or is it authentic?” Similarly, the reappearance of Trader Sam has prompted questions about why a character removed for racial insensitivity in the theme park was brought back, even in a revamped version. Other viewers have posted on Twitter about the film sidelining Indigenous characters who merely assist in the quest of the European main protagonists.

The film’s villains are obvious, as would be expected for a family movie, and they differ from those of the theme park ride. They include a German aristocrat leading a military expedition in hopes of obtaining the powers of the Tree of Life no matter the cost to the jungle, and a cursed group of conquistadors who had attacked the local tribe. Blunt’s Dr. Lily Houghton is the protagonist, but also an outsider entering the jungle with the goal of taking away something native to the land. Asked whether her character’s mission could be interpreted as exploitative, Green says that Houghton is not someone who would put herself front and center. “To my mind, she is the type of character who would credit where things came from, the people who helped her to it and would bring them into it,” he says.

Indigenous representation in TV, film and theme parks in the future

Seeing authentic and accurate representation of Indigenous peoples has lasting effects on young audiences, many of whom are the target demographic of Disney’s theme parks and films. Matias says that multiple generations of Americans have been taught while growing up, through watching TV and movies, that Indigenous peoples are savages. “They might grow up to be creators, producers, directors, writers, so if they have a little better understanding and were taught a little better history, then they might be able to form a better mindset as to what they’re writing about,” he says.

According to Francour, dehumanization of Indigenous peoples—like in the original Jungle Cruise attraction—is closely tied to depicting them as people of the past. “As an Indigenous person living in 2021, I myself am a modern person, I live in two worlds,” she says. She describes being immersed in her Indigenous community while residing in Chicago.

“I live in a big city, and I wear ‘normal’ clothes, I guess you would say, that aren’t my regalia when I go on the street,” she says. “To see this dehumanized illustration of our people as in the past tense, it just does not fully represent the diversity of who we are, then, now and in the future.”

Francour describes a growing movement of Indigenous communities and organizations that are changing past narratives by retelling stories from a first-person perspective. And, from non-Indigenous people, “there’s a growing movement of openness to connect and to consult and to collaborate with Indigenous peoples to make sure that their narratives are represented well,” she says. Francour gives the example of Disney partnering with the Sámi people for Frozen 2 with the goal of portraying the Sámi community—who were the inspiration for the fictional Northuldra tribe—in a culturally sensitive and respectful way.

“I think there’s a lot of opportunities where Indigenous peoples themselves can be centered,” she says. “We need to shift the power of who is producing this content, producing this narrative, and making sure that Indigenous people, and our leadership are at the forefront.”

Correction, Dec. 1

The original version of this story misstated the roots of the phrase “merciless Indian savages” in the founding of the United States. It appeared in the Declaration of Independence, not the U.S. Constitution.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com