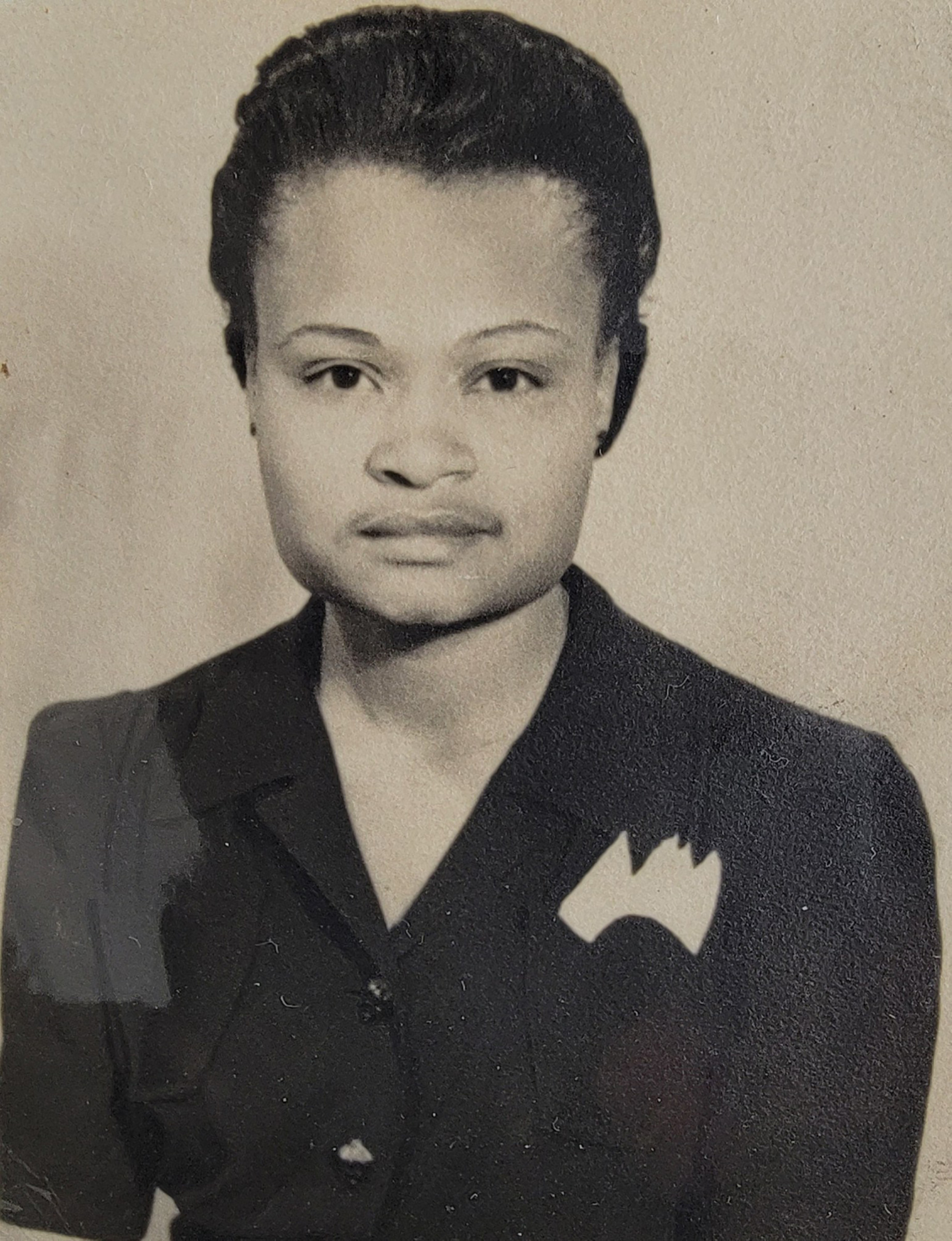

In the early days of her childhood, Viola Fletcher lived with her family in a house on the north side of Greenwood, a self-sustaining and thriving Black neighborhood of roughly 10,000 people in Tulsa, Okla., hailed as the “Black Wall Street.” With at least 191 Black-owned businesses, like the Williams Dreamland Theatre and the Stradford Hotel, its economic success and achievement became a source of aspiration for Black communities around the U.S. However, not everyone saw “Little Africa” as an American success story.

Even at the age of 107, Fletcher can still hear the sound of her mother and siblings singing, the melody of “Go Tell It on the Mountain” and other gospel hymns reverberating through the halls of their home. She smiles as she recalls the idyllic days of her childhood spent going to the local school, perusing the aisles of the many Black-owned stores, and attending Sunday services at St. Andrew, a Black Baptist church where she was baptized and where her older sister sang in the choir. On Sunday nights, the family would crowd around the dinner table for a big dinner of fried chicken, potatoes, beans, biscuits and cobbler.

Then in 1921, a single encounter would ignite deep-rooted racial tensions in Tulsa, ending in what historian and author of Death in a Promised Land Scott Ellsworth calls the “single worst incident of racial violence in American history.” On May 31, 1921, amid rumors that a Black teenager had assaulted a white woman in Tulsa, an errant gunshot led to a fatal clash between a white crowd and outnumbered Black Greenwood residents. But the white mob’s fury was about more than just the rumor: it was about the prosperous Black neighborhood, Ellsworth says. The white mob, some of whom were armed and deputized by white city officials, invaded Greenwood, wreaking destruction and havoc in their wake. In the dead of night, Fletcher’s mother frantically shook the family awake to flee as white vigilantes destroyed, burned and looted Greenwood businesses and residences.

Amid the rampage, the family left with nothing but the clothes on their backs. Nearly 100 years later, Fletcher still lives with the trauma of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Fletcher, the oldest known survivor of the Massacre, sleeps sitting up on a couch with the lights on. “Being in the dark, I can’t see how to get out. I can’t see who is coming in,” she tells TIME.

When she closes her eyes to sleep, her mind conjures memories of Black bodies scattered across Greenwood.

“People were falling and bleeding, crying and howling. I saw houses and burning cars. You could hear airplanes flying over the top. Somebody told us, ‘Hurry up, leave. They’re killing all the Black people,’” Fletcher says. “You just can’t forget that, my goodness.”

The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

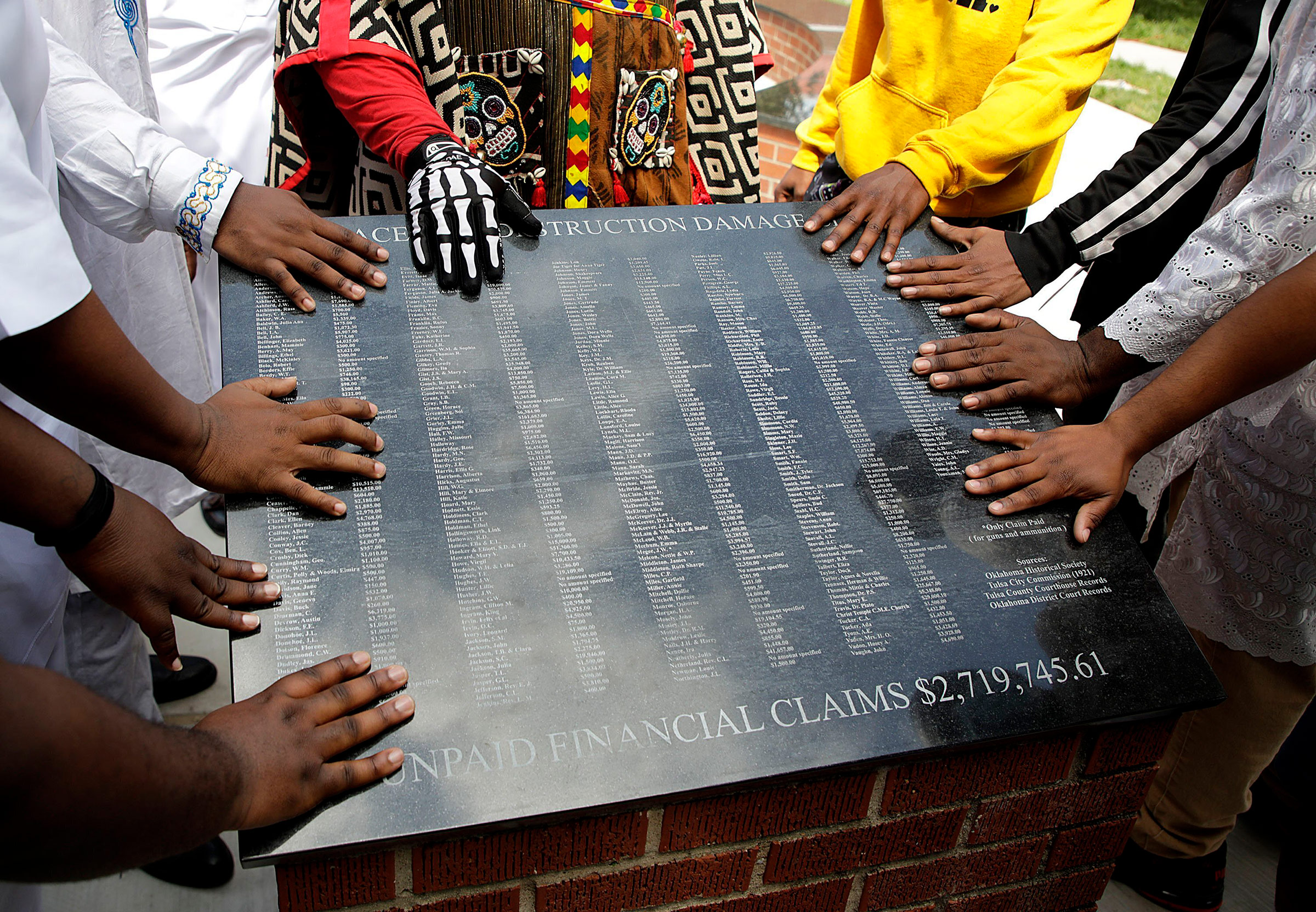

When the smoke dissipated on June 1, 1921, the entire 35-square-block neighborhood had been razed to the ground, with 15 years of accumulated wealth eradicated in hours. More than 1,200 homes had gone down in flames. The Tulsa City Commission passed strict fire ordinances that prohibited Greenwood residents from rebuilding. As many as 10,000 Black Greenwood residents were left homeless. And while the Oklahoma Bureau of Vital Statistics estimated that 10 white people and 26 Black residents died in the eruption of violence, Red Cross records estimated there were as many as 300 deaths. Efforts to find a reported mass burial site of Black Tulsans continue today.

In the wake of the destruction of their community, Black Greenwood residents tried to recover what was lost through insurance claims or lawsuits against the city, but all of these efforts were denied. Based on data from the Oklahoma Historical Society’s Tulsa Race Riot Commission Collection combined with Red Cross reports of the number of residential buildings and businesses destroyed, economic researchers at Harvard University estimate that the damage claimed from the Massacre would be anywhere from $32.6 and $47.4 million today. However, others claim the property losses could total up to $100 million.

The effects of those losses endured long after the smoke cleared.

According to a report on the economic effects of the Tulsa Race Massacre conducted by Harvard researchers, the Black population in Tulsa experienced a decline in homeownership, occupational status and educational attainment; average incomes were reduced by a “sizeable” 7.3 percent. They found that the socioeconomic devastation of the Massacre not only persisted over generations but grew over time. The “disruption, trauma, and economic loss” caused by the Massacre impacted the economic status and mobility of their children and grandchildren.

“By 2000, the estimated effect of the massacre on Black Tulsans is to reduce the probability that anyone lives in a home that’s owned by somebody in the family by 26 percentage points,” says Nathan Nunn, a professor of economics at Harvard, who notes that decades of research shows that building generational wealth begins with homeownership. For survivors and their descendants, including Fletcher and her family, the Fords—Fletcher is her married name—it would take generations to rebuild their lives.

“We should have generational wealth to pass on, but we don’t,” says Fletcher’s grandson, Ike Howard. “It’s been the other way around. We’ve been helping keep her afloat.”

‘Breaking the curse of the Greenwood Massacre’

After losing everything in the Tulsa Massacre, Fletcher’s entire family worked as sharecroppers. Living out of tents, they moved from one Oklahoma town to the next wherever help was needed. In those difficult years, she and her seven siblings spent their days toiling in fields with their parents instead of going to school.

“We picked cotton, shucked the corn, dug up potatoes—whatever harvests were in the garden or in the fields. We’d get up with daylight in the morning and work till dark in the evening,” she recounts.

As a teenager, Fletcher moved back to Tulsa to live with her older sister, Jewel, and was hired to work at the Kress Store on Main Street, a “five and dime” retail department store chain. On her way to work, she would walk down the very same streets she did as a child—but instead, white owned-businesses lined the street.

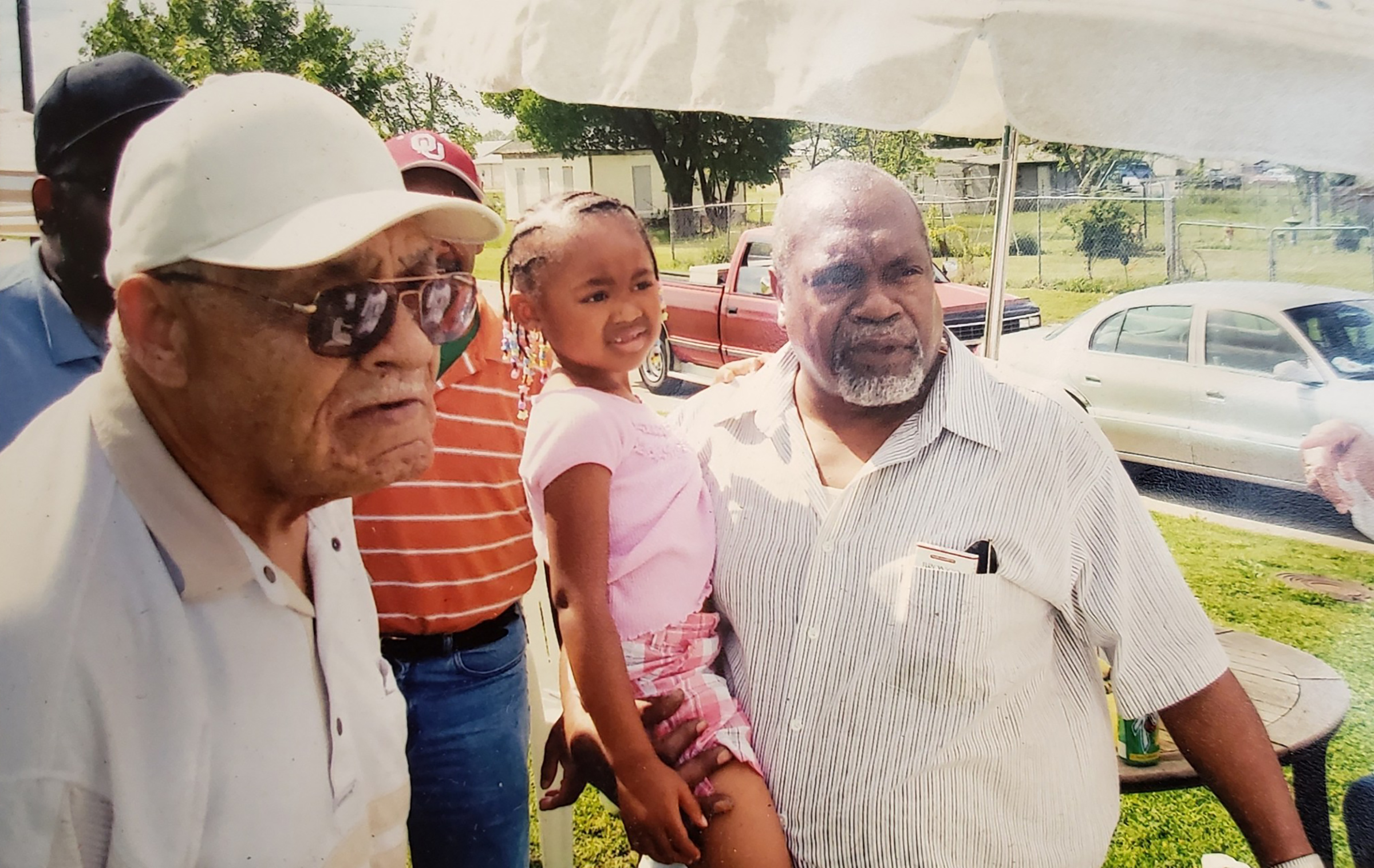

For Hughes Van Ellis, Fletcher’s younger brother, who was an infant when the family left Tulsa, the prosperous Greenwood of his sister’s childhood was a daydream constructed from the stories and memories of others. Instead, the 101-year-old recalls a childhood marked by grueling labor and an itinerant lifestyle.

Of the Black Oklahomans who were able to find gainful employment, many faced significant racial discrimination and unequal pay. Hoping to find jobs where they would be treated and paid better, Fletcher and her husband, Robert, moved to Sacramento, Calif. After World War II began, Fletcher worked alongside 90,000 men and women who worked to build warships at a record pace. Along with countless American women who had answered calls to join the war efforts, she was let go from the job after the war ended and expected to resume her role as a homemaker. The money she made helped the Fletchers buy a plot of land in Bartlesville, Okla., where they hired a Black carpenter to build them a home from “old lumber, bricks and rocks.”

There, she would raise her three children and, years later, her grandson, Ike Howard.

In Bartlesville, Fletcher maintained the sumptuous lives of Oklahoma’s elite, cleaning clothes and tidying rooms in private homes for affluent white families—many of whom she would later discover neglected to pay taxes for her social security, forcing her to work until the age of 85. Working long hours to make ends meet, her mother and grandmother helped care for her children until they were old enough to go to school.

“My family didn’t have everything we needed. We barely had enough to get by on so we could have used a lot more,” Fletcher. “It wasn’t probably right or good, but I managed.”

Harvard researchers found that “the disruption, trauma, and economic loss caused by the Massacre will tend to reduce educational attainment.” This was true for Fletcher’s two sons, including Howard’s father, James Ford, who chose to drop out of school.

“They would complain and say, ‘Well, you didn’t get an education. So why should I get an education?’” Howard, 54, says.

James obtained his GED through Job Corps, a department of labor job training program that provides free technical and vocational training for young adults with a demonstrated need. When James and Ike’s mother conceived Ike at the age of 16, his father was “forced to get it together” and joined the Navy.

Howard would remain with his mother in north Tulsa, growing up in a notorious, privately-owned housing project called Vernon Manor, seeing his father when he was on military leave. Then, his mother lost her job.

“I was a straight-A student, but my mother had gotten laid off from work. We didn’t have any food to eat and I got into trouble,” Howard recalls. Worried about his safety, his parents sent Howard to live with Fletcher. While Fletcher was unable to do what she wanted for her children, Howard says she “made up for it with her grandkids,” and took after him until he graduated from Bartlesville High School. Without the resources to go to college, Howard followed in his father and uncles’ footsteps and joined the armed services.

“I had to go to the military. I didn’t have a choice,” Howard tells TIME. “It was a way out of generational poverty because all of our generational wealth was stolen and our education was disrupted. The military paved the way for me to break the curse of the Greenwood Massacre.”

As a young girl learning in a classroom, Fletcher dreamed of becoming a nurse to “take care of people.” Now, generations later, Howard’s daughter and Fletcher’s great-grandaughter, Shani, has graduated high school and is on her way to Texas State University. With plans to become a pediatric nurse, Shani will have the opportunity to pursue and fulfill the dreams her great-grandmother could not.

‘A continual massacre in Tulsa’

Even in the face of the tremendous loss of wealth and structural inequities, many Tulsa Race Massacre survivors and descendants would rise above the devastation and defy expectations. Keewa Nurullah, whose great-grandfather ran a tailor shop in Greenwood, would also become an entrepreneur, starting Kido, a multicultural children’s store in Chicago. Massacre descendant Nehemiah D. Frank would start and lead his own publication called The Black Wall Street Times. Survivor Hal Singer became a saxophone virtuoso and a world-renowned musician. Massacre survivors even rebuilt Greenwood to its former glory in the early 1930s and ‘40s, until redlining and urban renewal efforts on the city and state level lead to its subsequent decline, according to a Human Rights Watch report.

While some have persevered in the face of these looming obstacles, survivors and descendants are still waiting for justice.

“There’s been a continual massacre since and the culture hasn’t changed in Tulsa. The railroad tracks at Greenwood and Archer divided the white side of town from the Black side of town back in 1921…it still symbolizes that racial divide,” Tiffany Crutcher, a descendant of a Tulsa Massacre survivor, told TIME in 2020.

Today, 33.5% of Tulsa’s Black residents living around the historic Greenwood area in North Tulsa live in poverty, compared to 13.4% of predominantly white South Tulsans. According to the 2020 Tulsa Equality Indicator report, the median income for a white family was $55,448 while Black residents’ median income levels off at $30,463. Beyond the long-lasting economic impacts of the Tulsa Race Massacre, the psychological trauma became a family inheritance, too.

“I’m angry. All of those years that I was in school I spent thinking, ‘We haven’t done anything; we didn’t create anything; we didn’t build anything,’” says African Ancestral Society Chief Egunwale Amusan, a descendant of the Tulsa Race Massacre. “All of that self-doubt just destroyed my self-confidence. Where I could be versus where I am was built on my ability to have hope.”

In September, civil rights attorney Damario Solomon-Simmons filed a lawsuit against the City of Tulsa and city entities for their role in the Tulsa Race Massacre and the “ongoing harm” on behalf of the last remaining survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre: 107-year-old Viola Fletcher, 106-year-old Lessie Benningfield Randle, and1 00-year-old Hughes Van Ellis, also known as “the big three of Black Wall Street.”

With the litigation, the Tulsa Race Massacre survivors and their descendants hope to establish a victim’s compensation fund to pay for all of the outstanding claims that were previously denied, scholarships for the descendants of those impacted by the Massacre, the construction of a hospital in North Tulsa and more. Last week, all three survivors and descendants made emotional testimonies before a U.S. House subcommittee asking that the Tulsa Race Massacre be acknowledged. Laws around the statute of limitations made it difficult for survivors and descendants to pursue legal claims in the past. So, Rep. Hank Johnson (D-Ga.) introduced the Tulsa-Greenwood Massacre Claims Accountability Act to help them get access to courts, paving a path towards reparations.

“We’re fighting for their dignity, their rights and the generational wealth that was stolen. And we fight for the opportunities that were taken,” Damario Solomon-Simmons, the attorney leading the reparations lawsuit, tells TIME. “We see this as a precedent for other Greenwood communities around this nation, who’ve also suffered such violence. If we cannot win in court, how can we win anywhere else in this nation?”

However, many Tulsans, including the current mayor of Tulsa, do not agree that reparations are the way to reckon with the city’s once-enshrouded history.

“Mayor G.T. Bynum has stated he does not believe this generation of Tulsans should be financially penalized for what criminals did 100 years ago, as the only option to bring monetary payments is to tax all Tulsans, including Black Tulsans,” Michelle Brooks, a spokesperson for Mayor Bynum, told TIME. Due to the pending litigation, the City of Tulsa and its mayor did not have any additional comment. However, Ellsworth, who spearheaded the 2001 Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot and chairs the committee overseeing the excavation efforts to unearth the mass graves disagrees, telling TIME that the survivors and their descendants “deserve economic restitution.”

“We need to pay reparations,” Ellsworth tells TIME.

Read More: What a Florida Reparations Case Can Teach Us About Justice in America

Today, Viola Fletcher lives by herself in an apartment in Bartlesville. Rather than pass on generational wealth, both she and her brother Ellis are supported by their family. But, her grandson says, even a lifetime that started out with such devastation did not stop her from doing everything she could to stop the cycle of generational loss. She now believes that, if successful, the reparations lawsuit would “change my life completely.”

“It would make me feel like a different person, being able to live in a better condition than what I’ve been. So many things: glasses, hearing aids, housing, clothes—anything money can buy,” Fletcher tells TIME, adding that she hopes to help put her great-granddaughter through college. “I’m one of the oldest survivors. I should be included in there.”

Nearly 100 years have already passed since the rampage disrupted and destroyed the lives of the survivors, countless have passed and still, they say they have not seen justice. In her emotional testimony before the House, Fletcher said “I pray that one day I will.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com