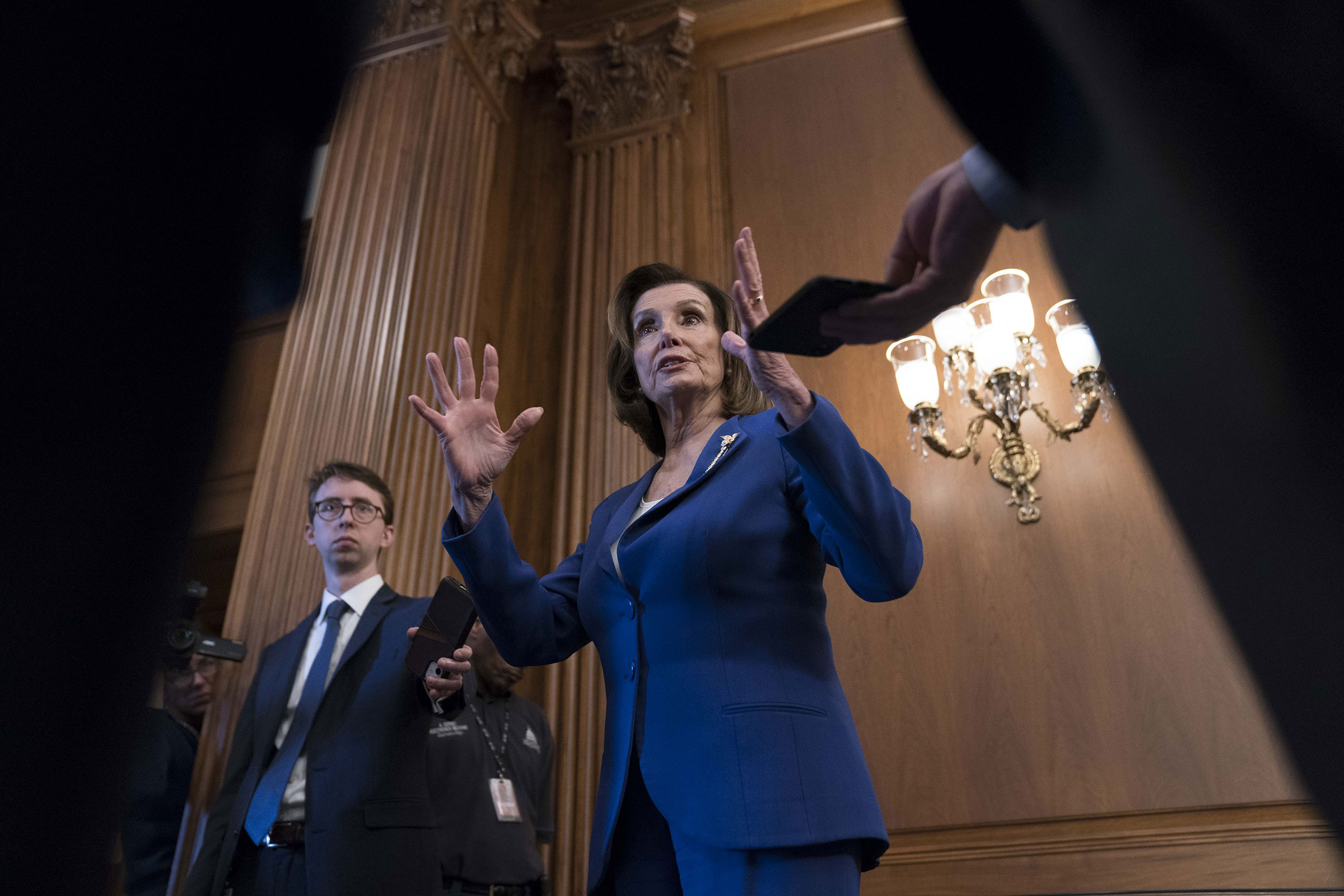

Nancy Pelosi was getting impatient. It was mid-March, and the House Speaker and her staff were working around the clock to draft urgent legislation to address the coronavirus pandemic. But the White House was dragging its feet: she hadn’t heard back from Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, her negotiating partner, in more than 12 hours.

Pelosi told Mnuchin the delay was unacceptable, and he got the message. The next morning, he boasted to Pelosi that his staff had been up until 4 a.m. putting the finishing touches on the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, providing funding for free testing, paid leave and expanded food stamps.

“I’m not impressed,” Pelosi replied. “We do it all the time.”

As the pandemic takes tens of thousands of lives and tens of millions of jobs, a Congress known for dysfunction has kicked into gear. Four massive bills with a price tag of nearly $3 trillion have sought to aid the sick, shore up the health care system, and ease the burden on workers and businesses. It’s the biggest federal outlay in history, dwarfing the response to the 2008 financial crisis, and as Speaker, Pelosi is naturally at the center of it. Before the ink was dry on the latest $484 billion small-business rescue package, she was on the phone trying to make the next deal to aid state and local governments whose budgets have been ravaged by the crisis. As Representative Karen Bass, a California Democrat, told Politico recently, “Quiet as it’s kept, she’s the one leading the country right now.”

Precisely because it required a frozen government to act, the pandemic has put Pelosi’s legislative talents on urgent display. It’s a fitting capstone to her historic three-decade career. Many congressional scholars consider Pelosi the most adept lawmaker of the past half-century, measuring her record of society-shaping legislation against the backdrop of the most partisan and gridlocked Congress in decades. While Republicans accuse her of obstruction, and some on the left accuse her of giving away the store, Pelosi believes she’s maximized her leverage at a time when inaction is not an option.

The legislative prowess Pelosi has exhibited during the crisis was honed in years of negotiations, often with the fate of the economy hanging in the balance. As Speaker from 2007 to 2011, she was instrumental in the U.S. response to the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent recession. As minority leader from 2011 to 2017, she forged deals in the high-stakes budget battles between President Obama and congressional Republicans.

For my new biography, Pelosi, I spent more than two years researching the Speaker’s life and career. I conducted more than 100 interviews with critics and supporters, activists and operatives, current and former staff, and dozens of current and former members of Congress from across the political spectrum. It’s the first biography the Speaker has cooperated with, offering extensive access to Pelosi and her inner circle. I found her to be someone everybody has an opinion about but few really know. Republicans have spent tens of millions of dollars over the past decade caricaturing her as a “San Francisco liberal,” while Democrats who once fought for her ouster have embraced her as a Resistance queen.

The woman who ripped up Trump’s State of the Union speech and led the most partisan impeachment in history is a loyal Democrat, but deep down she’s a dealmaker–an old-school legislator whose primary focus is getting things done through negotiation and compromise. Pelosi’s lodestar is securing the votes to deliver results. “Who would have thought Congress could pass four major pieces of legislation in the span of a month with overwhelming bipartisan support?” says former Representative Donna Edwards of Maryland, a onetime Pelosi lieutenant. “You can see it both in her command of the substance and also her command of the process. She’s not a politician; she’s a lawmaker.”

Since Pelosi arrived in Congress in 1987, America has embraced and endured massive change. But no one has ever dealt with anything quite like this–a double-barreled public-health and economic crisis of unprecedented proportions. In what’s likely the twilight of Pelosi’s historic career, a lot is riding on her ability to deliver the votes once again.

This is not the first time Nancy Pelosi has been called on to help a Republican President save the U.S. economy from collapse. On Sept. 18, 2008, Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson called Pelosi with panic in his voice. “A very serious situation is developing,” he said. The investment bank Lehman Brothers had declared the largest bankruptcy filing in U.S. history. The Federal Reserve and the Administration had done all they could, Paulson said. They needed help from Congress–fast.

The Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) would allow the Fed to buy up banks’ “toxic assets,” stabilizing their debt loads so they wouldn’t go broke. The plan would cost hundreds of billions of dollars. It was odious to both parties: Republicans hated the idea of government meddling so drastically in the economy (and spending so much taxpayer money to do it), while Democrats were loath to clean up the mess they blamed President George W. Bush for causing.

Over a week of intense negotiations, Congress and the Administration hammered out a bill. Pelosi and her GOP counterpart, John Boehner, made a deal: Boehner would come up with 100 Republican votes, and the Democrats would make up the rest–at least 118. Pelosi did her part: 140 of the 235 Democrats voted yes. But on the Republican side, just 65 of 198 were in favor, and the bill went down. The Dow’s 778-point fall was the biggest one-day loss in history at the time, wiping out $1.2 trillion in wealth.

A week later, Pelosi brought a new bill to the floor, a compromise worked out in the Senate. It passed, 263-71, with 172 Democrats and 91 Republicans in favor. She had played a pivotal role in saving the U.S. economy from catastrophe–and bailed Bush out, for the good of the country, at enormous political risk.

After Barack Obama won the election a few weeks later, the economy was still reeling, shedding hundreds of thousands of jobs every month. Obama wanted the House to put together a stimulus bill he could sign on his very first day in office. The price tag would be huge. The White House sought about $800 billion in stimulus–bigger than TARP. As a share of GDP, it would be the largest public investment in U.S. history.

Obama tried to reach out to the GOP, even though Pelosi warned he was being naive. Charlie Dent, a moderate from Pennsylvania, was among the Republicans invited to watch the Super Bowl at the White House, where his wife chatted with Michelle and his kids played with Sasha and Malia Obama. In the end, Dent voted against the bill–and blamed Pelosi. “I believe the President was absolutely sincere in looking for a bipartisan outcome,” he told Newsweek. “But the White House lost control of the process when the bill was outsourced to Pelosi.”

Every single House Republican voted against the stimulus, as did 11 Democrats. But it still passed by a healthy margin. The key to Obama’s triumph had been not his ability to reach across the aisle, but Pelosi’s skill at holding her caucus together.

Over the ensuing two years, Pelosi helped Obama pass the Affordable Care Act, providing universal access to health insurance–something Democrats had been trying and failing to achieve for the better part of a century. In the 2010 midterms, Republicans cast her as the villain, spending $70 million on ads that tied Democratic candidates to her. The chairman of the Republican National Committee embarked on a 117-city “Fire Pelosi” bus tour. It worked: in November, the GOP won 63 seats and the majority.

Pelosi stayed on as minority leader as Obama and the new Speaker, Boehner, tried to figure out a way to strike a grand bargain to balance the country’s books and restore Americans’ trust in government. When Pelosi found out about the talks, she was publicly critical of Obama’s willingness to cut entitlements such as Social Security and Medicare, totemic achievements of past Democratic administrations that had rescued millions from penury and sickness. Privately, she assured Obama that if he needed her, she would be there. But who, she wanted to know, was counting votes? Republicans, she suspected, were just going through the motions, waiting to blame it on the President when the deal fell apart. Within a couple of weeks, that was exactly what happened.

On the eve of a national default that could have shaken the market and sent the fragile economy spiraling, Congress took over the talks. The solution congressional leaders came up with wasn’t pretty: no entitlement reform, no new taxes, but the formation of a bipartisan “supercommittee” that would have 10 weeks to come up with more than a trillion dollars in cuts and revenue. Failure to do so would trigger automatic across-the-board cuts to the entire federal budget. Pelosi, now at the table, secured important concessions: the trigger would hit defense spending just as hard as domestic spending, and there would be no changes to Social Security, Medicare or Medicaid. Democrats hated the deal–Representative Emanuel Cleaver, a pastor from Kansas City, Mo., called it a “sugar-coated Satan sandwich”–but the bill passed with 95 Democratic votes.

This pattern would define the remainder of the Obama presidency: a cycle of crisis, featuring marginalized Democrats, recalcitrant Republicans, a White House unwilling or unable to strategize around them, and a government that could barely keep the lights on, much less solve any of the nation’s pressing problems. Another recurring feature of this depressing cycle: Pelosi, the congressional leader with the longest track record of reaching across the aisle, was routinely cast aside. When she forced her way into the room, problems generally got solved. But it didn’t seem to occur to the men in charge to invite her in the next time.

Pelosi’s current efforts have a political goal: as the November election nears, she wants to show that Democrats are focused on governing responsibly. It’s why she’s urged the party’s candidates to focus on kitchen-table issues and realistic plans; it’s also why she resisted impeachment for the better part of a year, then pushed for a short and simple process.

“The message has to be one that is not menacing,” she told me in December, when both impeachment and the presidential primary were in full swing. “People love change, but they also are menaced by it.” The liberal platform that resonates in her San Francisco district, she said, may not go over as well in swing states like Michigan that Democrats need to win the Electoral College. She cited single-payer health care as an example: “I think it’s menacing to say to people, in order to get this tomorrow, we’re taking away your private insurance.”

Pelosi’s political future isn’t something she talks about–when I mentioned the idea of the “twilight” of her career, she snapped at me–but in 2018, she accepted a term-limit agreement that would force her to step down in 2022. Privately, as I reveal for the first time in the book, she told confidants at the time that she expected the current term to be her last.

The legacy she leaves will be a complex one. As the first female Speaker, she shattered the “marble ceiling,” but her dreams of a woman President were dashed in 2016 and 2020, and she leaves no obvious female successor. She cites the Affordable Care Act as her greatest achievement, but Republicans have succeeded in undermining it and Democrats argue it doesn’t go far enough. Despite her willingness to deal, Congress is a gridlocked mess with dismally low approval ratings.

When I asked Pelosi what she still wants to accomplish, she pointed to the problem of income inequality and the “existential threat” of climate change. Pelosi’s House passed a cap-and-trade bill in 2009, but it never advanced in the Senate; save for a resolution last year in favor of the Paris Agreement, it remains the only major climate legislation ever to pass a house of Congress.

“Our work is not finished,” she said, “when it comes to improving the lives of the American people.”

Adapted from PELOSI by Molly Ball. Published by Henry Holt and Company May 5th 2020. Copyright © 2020 by Molly Ball. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Molly Ball at molly.ball@time.com