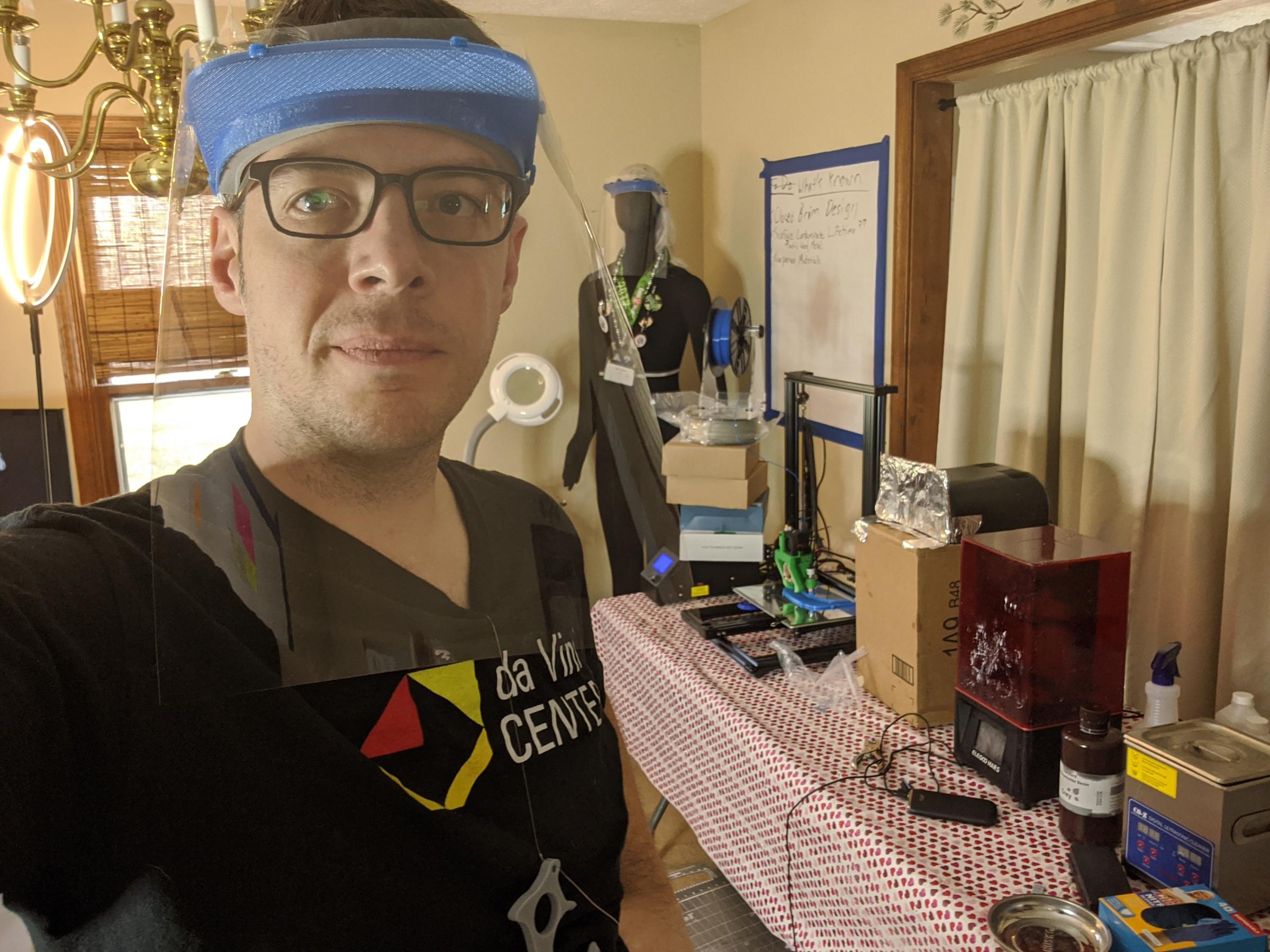

While most of Adam Gainer’s family works in the medical field, the career path never interested him. Instead, the 35-year-old pursued engineering and design; he’s now working on a master’s degree in product design and innovation at Virginia Commonwealth University. But the global pandemic has thrust him, and thousands of other engineers, designers, and self-styled “makers,” into the healthcare world, producing gear for medical workers on the front lines like modern-day Rosie the Riveters.

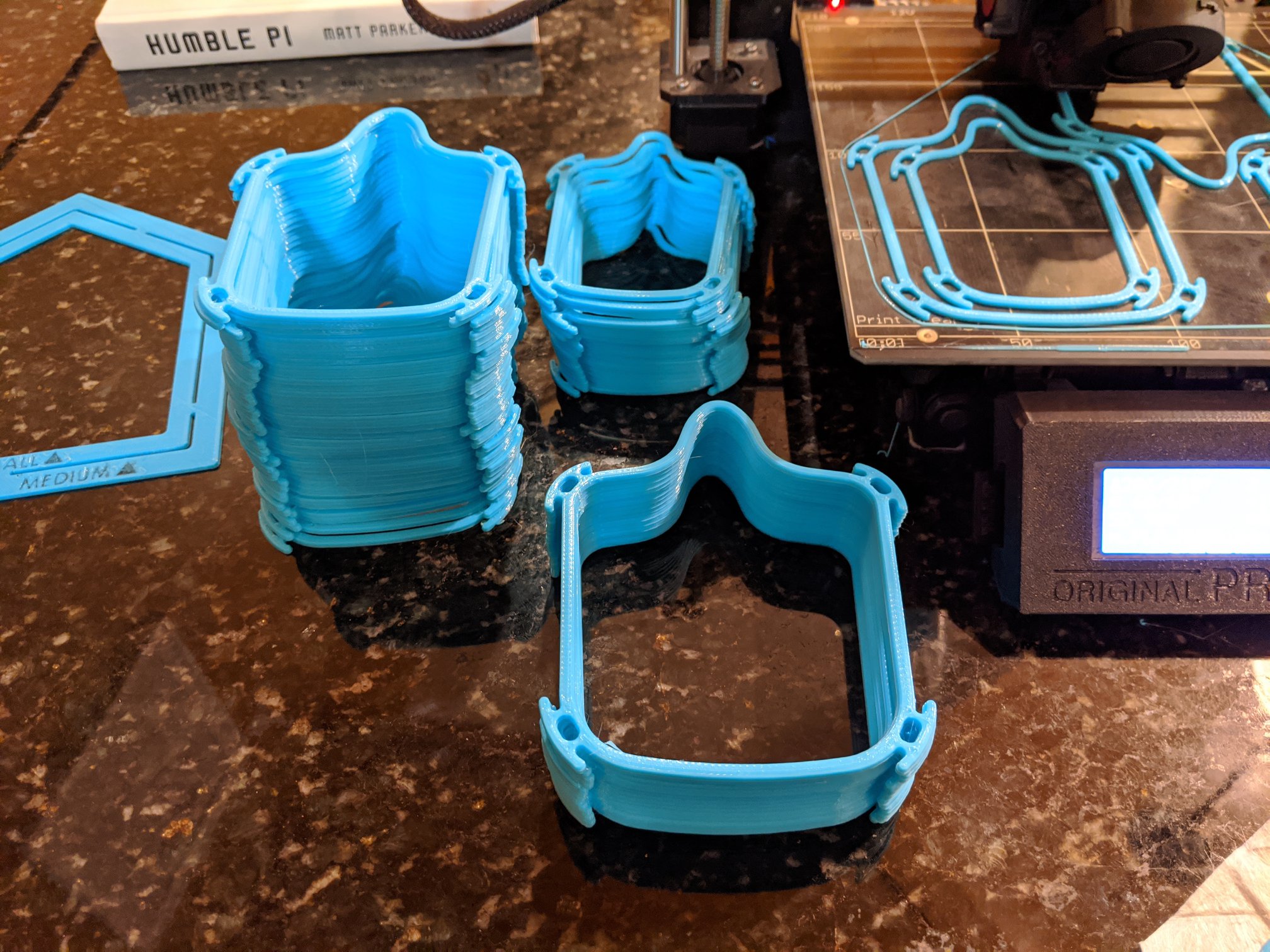

“I can’t make N95 masks, I can’t make ventilators, but I sure as hell can make face shields,” says Gainer, who’s also making 3D-printed door openers with the organization Shield Healthcare Workers. “Elastic, foam, glue, I did that ever since I was in kindergarten.”

As the novel coronavirus continues to spread, many American health care workers say they’re facing critical shortages in everything from personal protective equipment (PPE) to ventilators. While major companies like Ford and General Motors are retooling their factories to produce medical equipment, “makers” like Gainer are also stepping up to help, firing up their CNC routers, 3D printers, and even sewing machines. The maker community prides itself on self-sufficiency, sharing data, and being nimble — all qualities that stand to help in this time of crisis.

Thousands of makers are turning to one Facebook group in particular, Open Sourced Medical Designs, to share instructions, offer tips and encourage one another. The group, which has 52,000 members, is dedicated to collecting, vetting and disseminating open-source designs for everything from hand sanitizer to non-contact thermometers. It was founded by Gui Cavalcanti, the founder and CEO of Bay Area robotics firm Breeze Automation, and Ja’dan Johnson, founder of educational nonprofit Next Gen Creators. The pair are working with a team of 30 doctors and other experts to review and approve submitted designs. Because the designs are open-source, anyone can see the instructions and suggest changes, like a Wikipedia page.

Cavalcanti hopes the group’s efforts will help mitigate any potential disruptions in the medical equipment supply chain due to the coronavirus. “We will have supply chain failures across the board,” argues Cavalcanti. “There will be no Amazon to send you a face shield or an N95 [mask]. And so we must prepare for a time when local manufacturers, whether that’s some guy in a garage, a set of people in a maker space or a professional injection molding fabrication house, all of those people will need to retool. And in order to retool, they will need plans.”

Jonhson says the project’s goal is to help everyone from well-resourced manufacturers to total amateurs learn how they can help provide needed supplies in a time of crisis. “[I]f you’re a manufacturer, you’re a hospital, or even a mom with a sewing machine and you want to figure out how to help your local hospital, then you can … learn how to get involved,” he says.

Indeed, plenty of people with just a sewing machine are getting involved. In mid-March, Kirsten Hawkins began a Facebook group dedicated to sewing masks for Atlanta-area health care workers. The effort exploded, quickly gaining more than 6,000 members and expanding nationwide. While experts say homemade masks don’t offer the same level of protection as professionally-made equipment, some argue that something is better than nothing. Hawkins says that more than 50 medical facilities have reached out to her for masks; the group has already made and distributed over 10,000 masks across Georgia.

“We wanted to be the central way that we could disseminate information to our community so they didn’t feel overwhelmed and they had the resources and support they needed to dust off their sewing machine at home and be a part of this movement,” says Hawkins. “The group is everyone from moms who have kids at home to people who are unemployed right now because of the crisis … We’ve got grandmas, we’ve got aunts, it’s just literally anyone who has ever wanted to sew a mask and not feel helpless and feel like they were a part of something bigger than themselves.”

Other makers are focused on life-saving hospital equipment like ventilators, which help patients who have difficulty breathing on their own. Because COVID-19 often causes respiratory symptoms, ventilators have become a key part of treatment, but they’re in short supply across the country.

While some makers are hesitant to tackle complex hospital equipment like ventilators — and hospitals are even more hesitant to use unapproved ventilators — that hasn’t stopped inventive people from finding ways to expand the usage and capacity of the life-saving machines. In New York, actor and model Angel Pai teamed up with Timothy Phillips and designer Philip Sweeting to form Keep Breathing NYC, a group established to 3D print a “splitter” for ventilators that can possibly allow for more than one patient to use a single machine by dividing oxygen and pressure through a split valve. It’s a very risky way to use a ventilator, as the machines are designed for only one patient, but the technique has been reportedly used in emergencies like the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting.

“This works, but there are many, many complications and we’re aware of them,” says Pai. “This is truly a last resort. We’re very aware this just buys you time until the new machines show up. This buys you time.”

Pai says that while hospital administrators aren’t reaching out, doctors and others on the front lines are. “I’m hearing it from the doctors on the front line: ICU teams, surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses,” says Pai. “Instead of doctors trying to finagle it in the last resort, I’m trying to say, ‘we printed some. It’s here. Use it if you need to. But I really hope you don’t need to use it.’ This is a last freaking resort.”

Still others are helping people find ways to minimize their risk of contracting COVID-19 in the first place. Materialise, a Belgian design company, has published instructions for 3-D printing a device that lets people open doors with their forearms, reducing the chance of contracting the disease from a doorknob or handle.

“Door handles are a hotspot for viruses, everyone is touching them with their hands and then touching their face,” says Materialise public policy officer Bram Smits. “A local supermarket manager called our solution ‘a blessing’, retirement homes in Belgium … started printing the door handles on their home, and Mayo Clinic started printing these in their in-house printing center.”

While some medical experts were skeptical of maker-produced gear at first, some are embracing the help as the situation becomes more dire. Dr. Guillermo Tearney, a chair pathologist at Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital, is part of a team looking into “alternative supplies.” He says the trick is to separate the wheat from the chaff, identifying the potentially useful ideas while skipping the less promising ones. Having visibility into the construction process is key as well, he says.

“Control over a process is very important for a medical device,” says Tearney. “And if we don’t have some level of control over the process, you’re probably asking for some problems to crop up in the safety profile of the products that people are using.”

Tearney remains hopeful that he won’t need maker-produced gear at all. “All of this is a last resort,” he says. “Nobody is going to be using 3D-printed ventilators if there are ventilators in the hospital ready to use. We’re preparing for a doomsday, last-case scenario where there is no other option. This isn’t normal times.”

For many in the maker community, the secondary goal is to give people some sense that they’re able to help fight an invisible, deadly enemy. “This isn’t an engineers, 3-D printer only movement,” says Johnson, of Open Sourced Medical Designs. “We want the everyday person to understand how is it they are able to help with addressing some of the needs that are coming from this problem.”

Those in the medical field agree that’s useful in and of itself. “In the end, whether these devices are used or not, it’s going to be a very positive thing,” says Tearney. “Even if nobody uses a single 3D-printed PPE device. There’s been a tremendous amount of creativity, of people working together and a lot of things that we can grow from as we emerge from this crisis.”

And for Gainer, the work has grown deeply personal.

“If any single one of my face shields were to help a single person, then I feel like all my energy and time has been worth it,” he says. “People need to know that there are people out there working nonstop so that we can get through this and we can get back to our families. Sunday was my mom’s birthday, and she’s an at-risk individual and she’s been a nurse for forever. Honestly at this point, all I want to do is hug my mom.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Peter Allen Clark at peter.clark@time.com