Robyn knows where she’s going—more than I do, at least. It’s a cloudy day in London and we’re standing outside a convenience store, both of us staring at our respective phones, trying to navigate to the National Gallery. I keep rotating, trying to get oriented to the mazelike intersection of streets. “I think we go this way!” she says brightly, pointing down one road. She sets off in that direction, her backpack-—half-unzipped, its contents visibly jostling—-bobbing behind her.

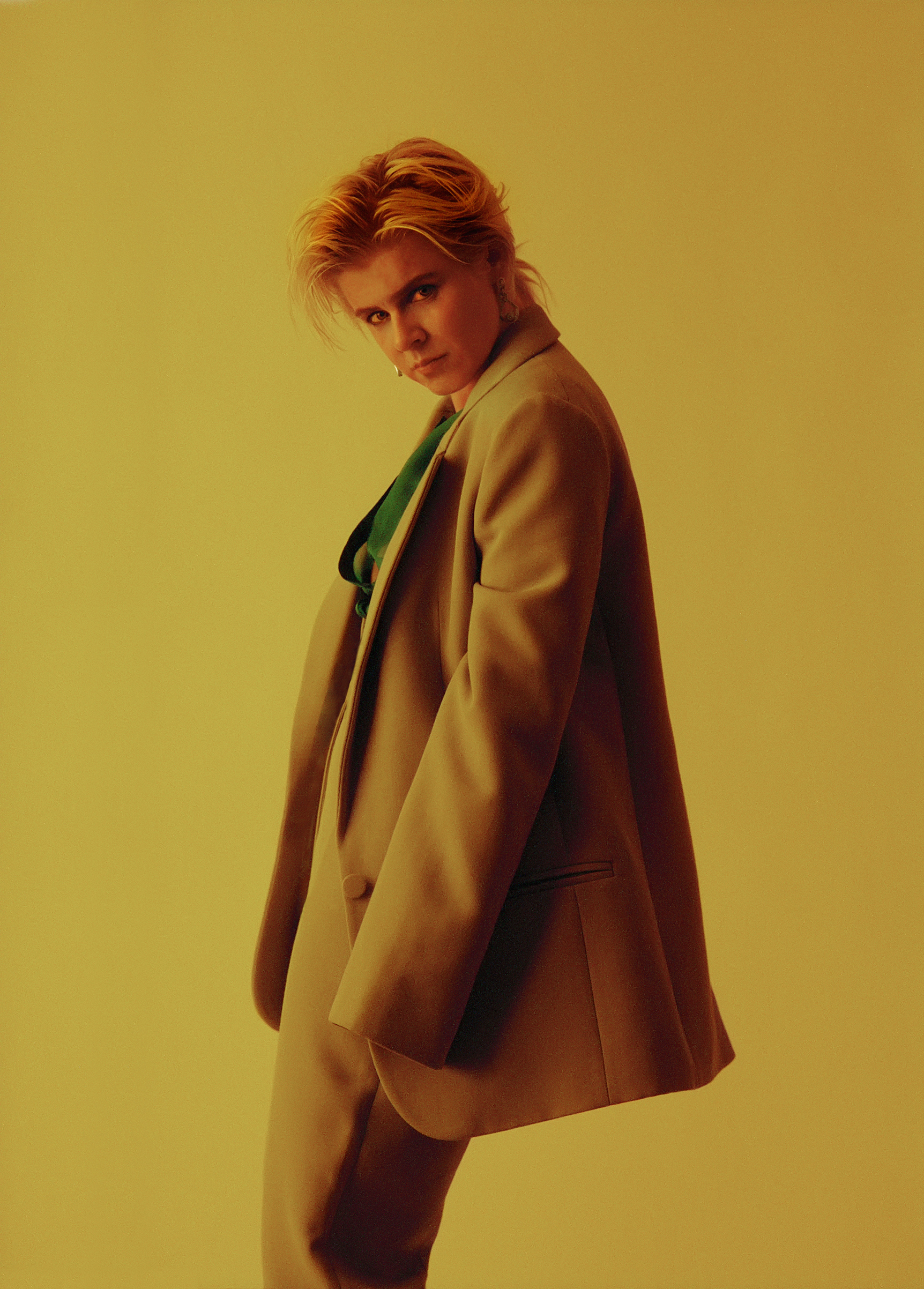

The singer, 39, is disarming and unpretentious. Her platinum blond hair is cut boyishly short. She’s wearing next to no makeup and a camouflage–print Jean Paul Gaultier jacket. As I follow her through Leicester Square, crowded with tourists, nobody stops her or even does a double take.

But if Robyn does not move through the world like a pop star, it’s also true that she is not like most of them. She’s a singer, songwriter and producer who has spent the past two decades being quietly peerless. Her last album, 2010’s Body Talk, served as a blueprint for the sound of mainstream music in the decade that followed: from Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe” to Taylor Swift’s 1989, you can hear Robyn’s influence—bright synths, perfectly symmetrical choruses and more than a whiff of melancholy. When Lorde performed on Saturday Night Live last year, she did so with a framed photo of Robyn above the piano. Earlier this year NPR called her “the 21st century’s pop oracle.”

Body Talk, which spawned the cult singles “Dancing on My Own” and “Call Your Girlfriend,” marked the biggest moment yet for the artist, born Robin Miriam Carlsson, who had been working steadily since the mid-’90s: first as a teen pop sensation with a pair of Top 10 hits in the U.S., and then as an indie dance star releasing music through the ’00s via the label she founded, Konichiwa Records, collaborating with electropop experimentalists like the Knife and Röyksopp. But after the global success of Body Talk, which earned her two Grammy nominations and legions of new fans, instead of capitalizing on all that momentum, Robyn went dark. “I needed to take time off when I made this music, and I did—-because I was in a life crisis,” she says now over lunch at a tapas restaurant in Soho. She was depressed after going through a breakup with her longtime boyfriend Max Vitali. (They have since reunited.) She was also grieving the death of her close friend and collaborator Christian Falk, who was -diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2014 and died several months later. “I was very raw,” she says.

She had never been depressed before—not like that. “I think I had it coming,” she says. ���It was waiting in the shadows. I would always work my way out of anxiety. But when I was in this depression, that didn’t work. And all these other things that I needed to deal with came up as well: childhood, relationships, [anticipating] turning 40. All of it at the same time.” She worked on a few collaborations and side projects, but she felt stuck. “I felt like I didn’t want to make music,” she says. “I couldn’t catapult my way out of it.”

She began going to therapy several times a week. And she gave herself time to feel everything. She started to find a groove again in the physicality of the music she was making, in the way beats made her body rock back and forth. “The only way I could make music was to start making it in a way that made me feel better,” she says. Her new music wasn’t as crisp and mathematical as the clean pop songs that earned her such a devoted following. These songs felt different to her: more personal and more visceral. “It became all about pleasure,” she says.

It takes a couple of listens to begin to understand the album Robyn ended up writing, which is called Honey. But once it clicks into place, it’s as satisfying as anything she’s ever released. The first single, “Missing U,” serves as connective tissue between the last era and this new one: it’s sparkling, half-euphoric and half-elegiac. But nothing else on the album has that familiar texture—least of all the title track, which might be Robyn’s masterpiece. It’s layered and psychedelic, like a Balearic dance party—more tactile than sonic. “I spent more time on that song than I did on any other piece of music in my whole life,” she says. “You know when you have those experiences that are fundamentally changing, or spiritual, almost? I wanted to make sure the song explained that. I wanted it to be more than mood. I wanted it to be a physical feeling.”

What kind of feeling? She sighs. “When you go through big changes,” she says slowly, “when people die, or you break up with someone, -whatever—-it destabilizes you in this intense way.” The years she spent feeling lost changed her indelibly. “It wasn’t about coming back to a normal life,” she says. “I don’t think I’ll be able to go back to feeling the security that I felt before—that’s gone. I’m so much more aware of how unstable the world is. Even the things we take for granted …” She grips the edge of the countertop with her hands and shakes it for a second, as if trying to lift it off the ground. The only things that felt truly sturdy were her connections—with other people, with her music, with herself.

Maybe that’s why Honey feels so different: because it’s not about anything as simple as a broken heart. What she’s wrestling with now is more existential than that. In Robyn’s old songs, the images of hurt are vividly external: she makes the dance floor a battlefield for the heart, twirling alone in a disco in “Dancing on My Own,” or, as in her other best song, “Be Mine!” she stages a scene of anguish at a train station, where she watches an ex bend down to tie his new girlfriend’s shoelaces. On Honey, she’s reaching out in the dark, trying to make a connection, in songs that are atmospheric and full of white space, instead of dense with glittering synths. Her lyrics are plaintive and straightforward, like: “Come get your honey.” Or: “Baby, forgive me.” Or: “Don’t give up on me.”

That last one is from a song called “Human Being.” On the chorus, she sings over and over again, “I’m a human being.” The song never reaches a triumphant refrain. But it’s beautiful and sad, even if it doesn’t sound like anything Robyn’s done before. “The idea of getting to the chorus wasn’t as interesting to me anymore,” she says. Writing these songs was a different kind of drug. “It was like tripping on sadness.”

Once we finally make it to the National Gallery, Robyn wants to find paintings by Caravaggio, the Italian Baroque painter. His work, she says, is so sensual: “All those naked women thinking about God.” She loves the hedonism of these paintings, the way they celebrate pleasure.

But we end up breezing past many of the round-bellied nudes to stop instead in front of a Caravaggio painting called Boy Bitten by a Lizard. The subject is a young man, his shoulder exposed, his hands contorted like claws. The expression on his face is exquisite—some agony (from the titular lizard bite, presumably), but also a feeling that’s otherworldly and possessed. We look at it for a long time. “This is the one I wanted to see,” she says.

She listens to the audio guide, her eyes widening as she reacts to the narration. “Listen to this,” she says, putting the headphones over my ears. An art historian is explaining that the painting is typically perceived as an allegory for the five senses: it’s about experiencing everything—even the pain.

It’s just like the sounds she’s been chasing. Those luminous swells of feeling, all of it—the joy and the sadness, the dancing and the crying, the high and the comedown. And here we are, all these centuries later, still trying to find the best way to express this thought: how good it all feels, and how badly it can hurt, when you’re a human being and vulnerable. When you have to stay in both the light and the dark.

Caravaggio was a pioneer of that technique; he called it chiaroscuro. It’s on Robyn’s face even now as she studies the painting. “You know, at the end of the day,” she says, “we’re all just human beings who will die.” And then she covers her face with her hands and laughs.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com