The great LIFE photographer Margaret Bourke-White was in Tokyo in 1952 when she first discovered that, in the middle of a physically demanding photojournalistic career, the dull pain in her left leg was becoming something more. Rising from a meal, she found herself, for a few steps at least, unable to walk.

As she would recount in an extraordinary LIFE story seven years later, it turned out — after years of misdiagnosis and confusion — that her brief stumble was a symptom of the onset of Parkinson’s disease, against which she would fight with everything she had for nearly two decades until her death at 67. It was, as the introduction to that 1959 article noted, the toughest battle ever faced by a woman who had seen many — including literal battles in World War II, during which she served as the first woman accredited to cover the combat zones as a photojournalist.

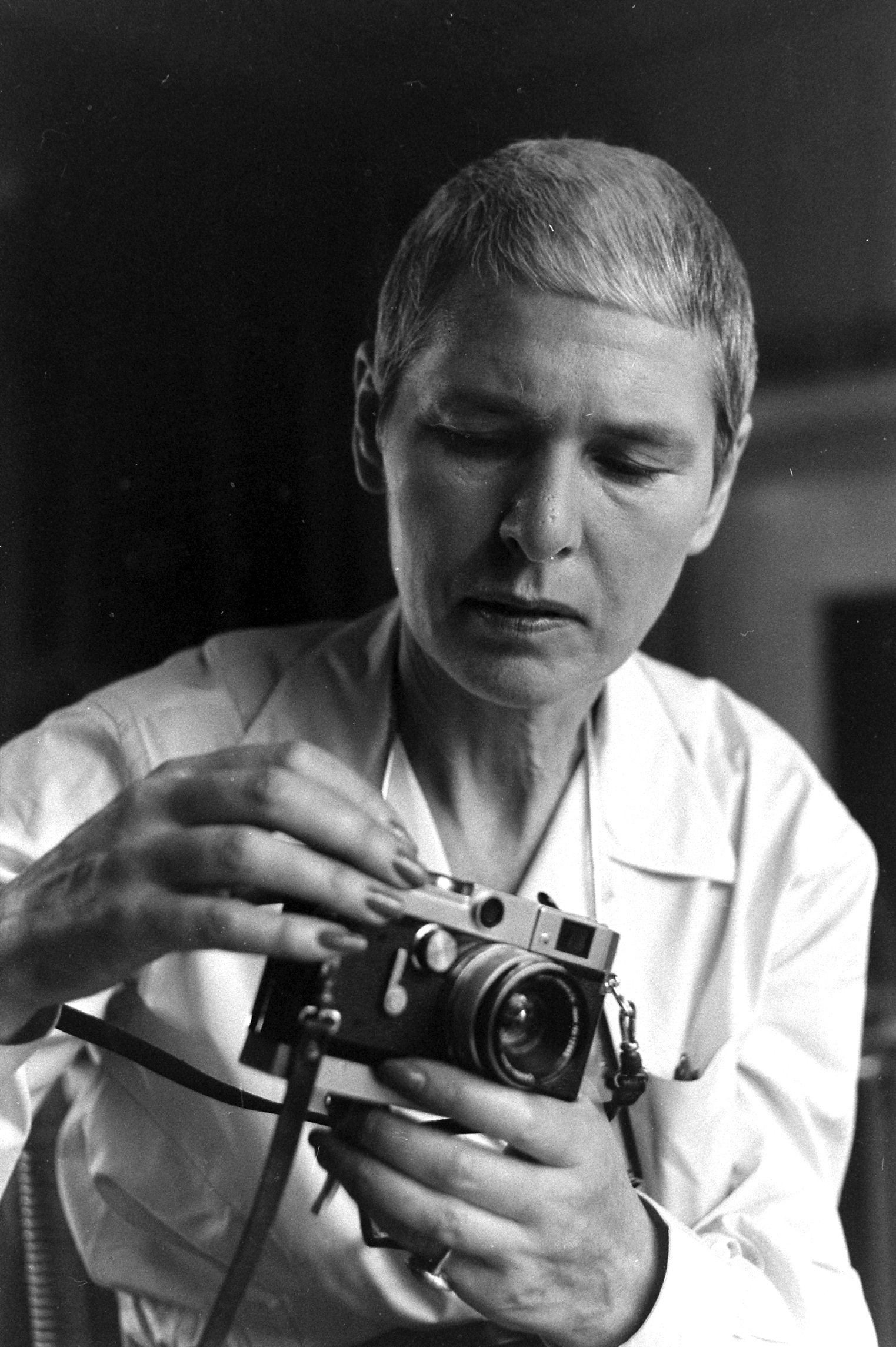

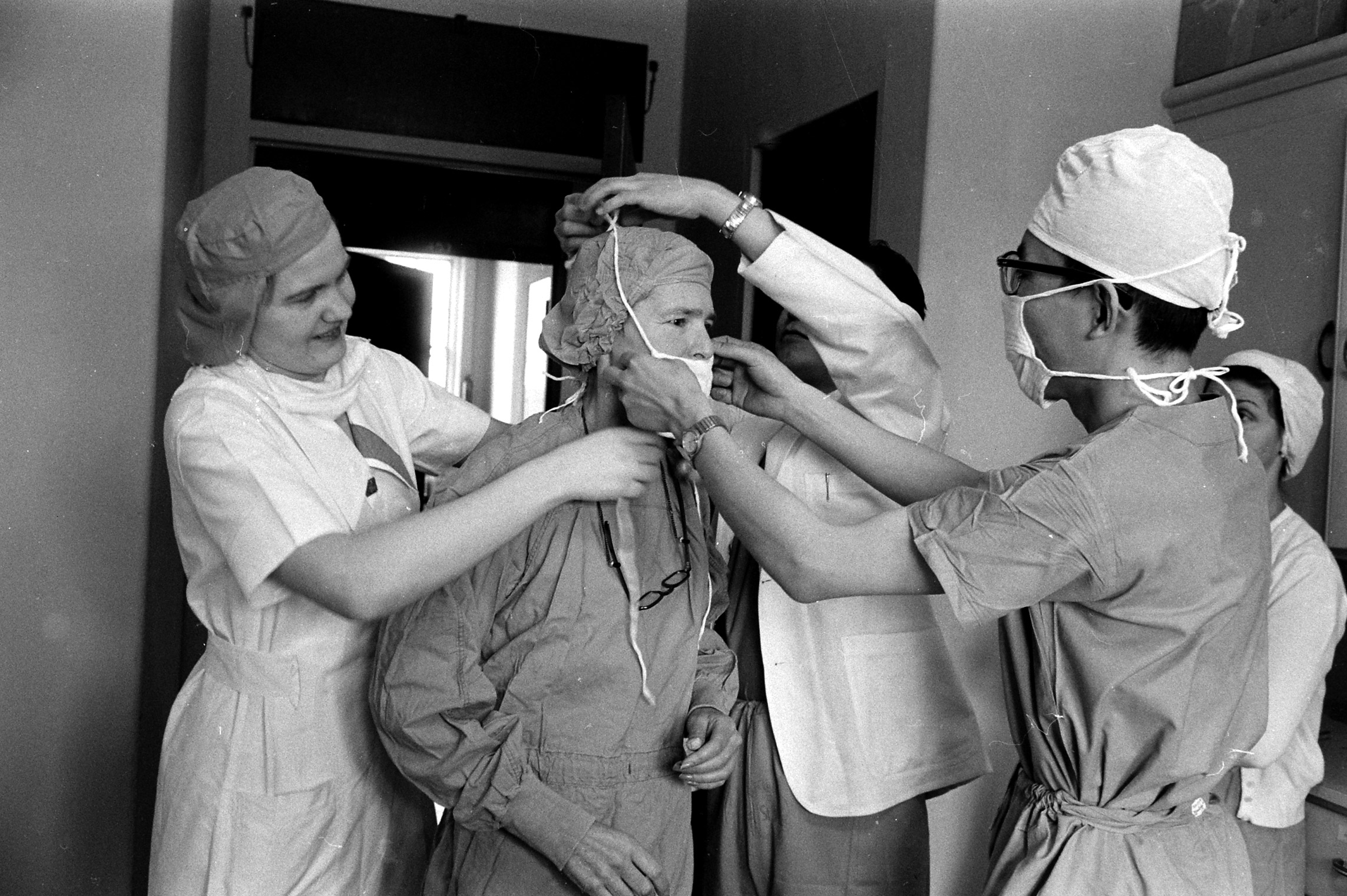

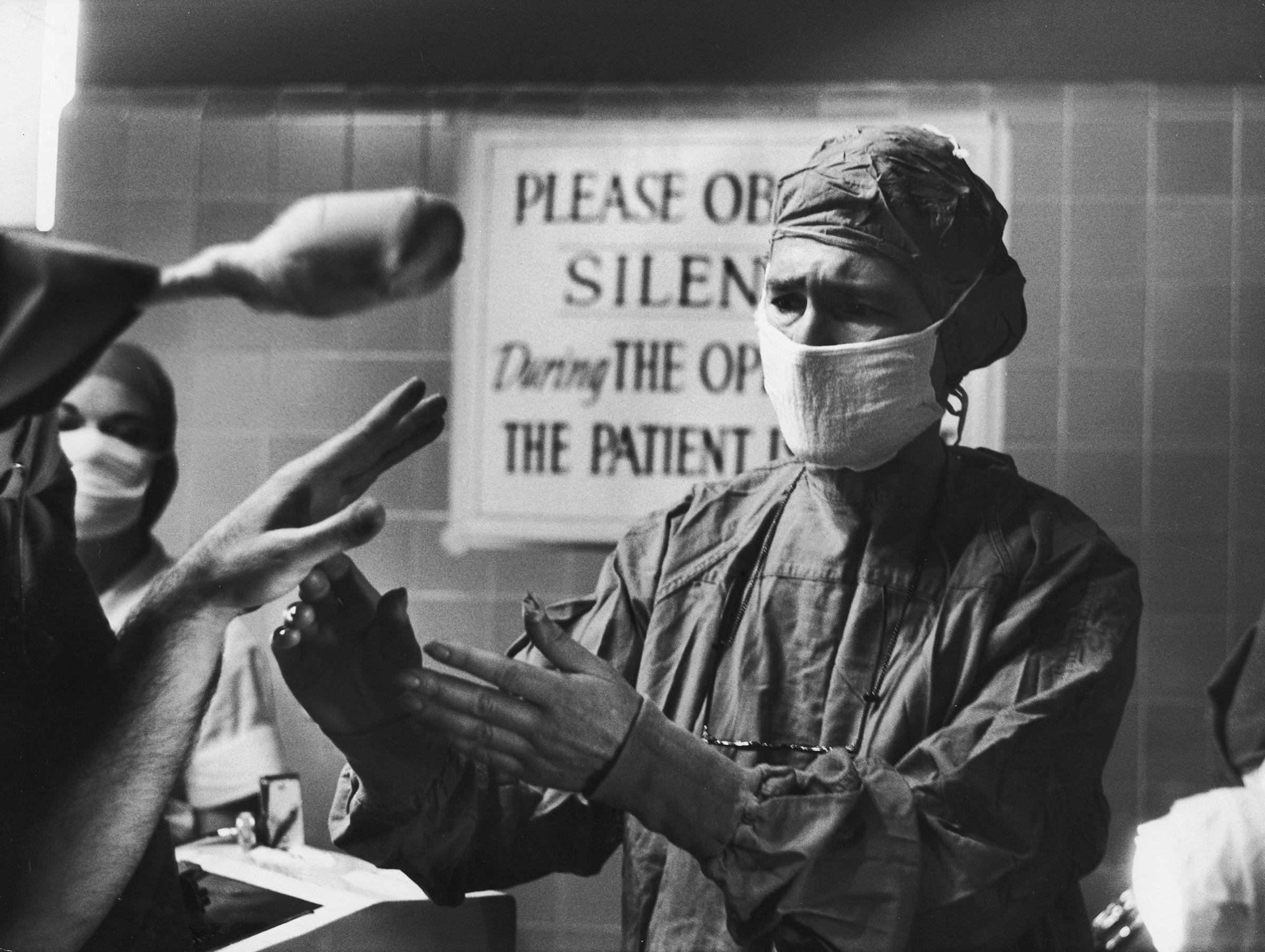

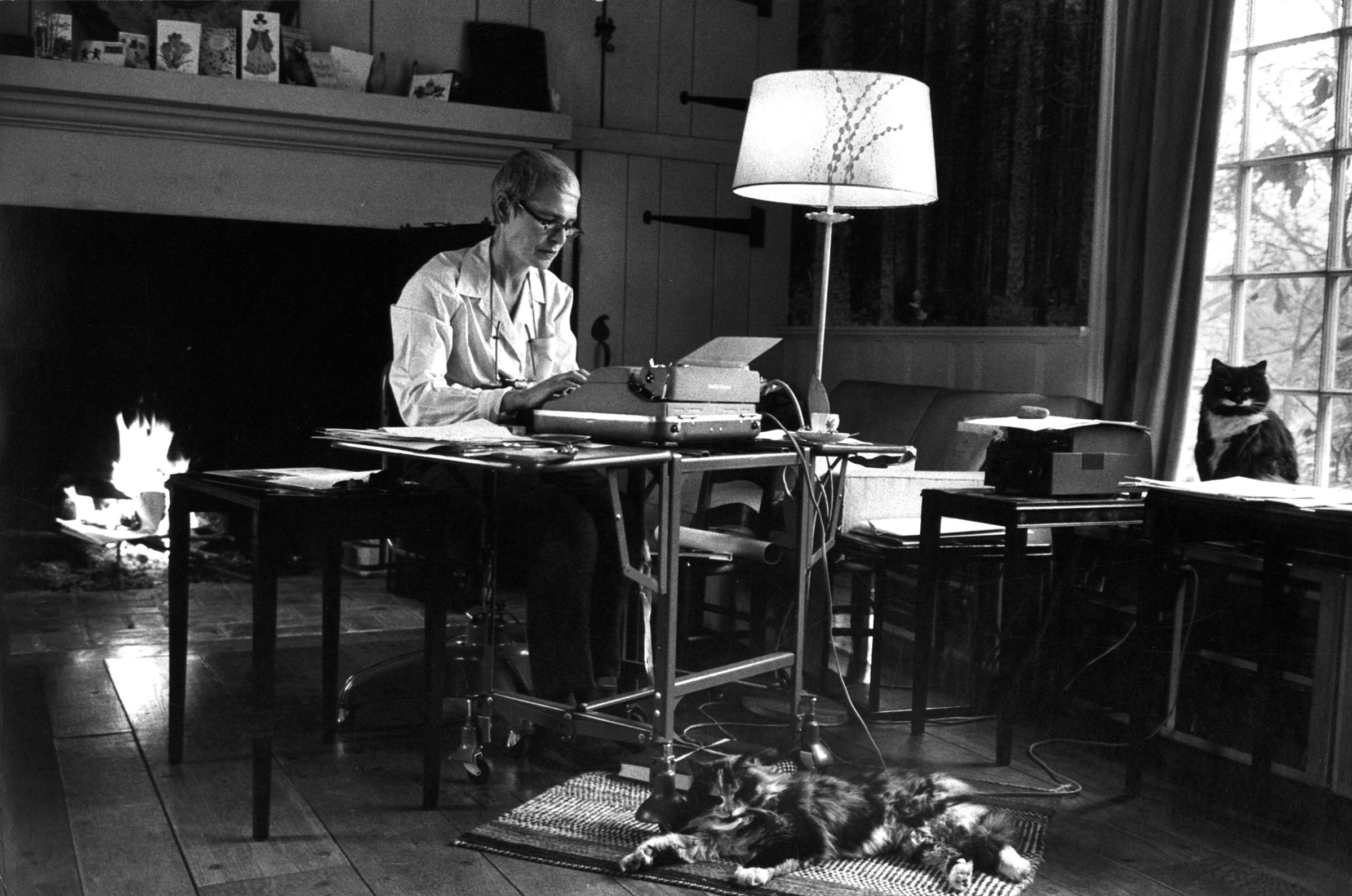

With photographs by her fellow LIFE photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt, some of which are seen above, the story offered up the personal reflections of the woman who had taken the image that appeared on the first-ever issue of the magazine.

“When I opened some medical insurance papers one day and learned I had Parkinson’s disease, the name did not frighten me because I did not know what in the world it was,” she wrote, describing how she learned the name that her doctors had kept from her as they prescribed physical therapy for her unlabeled symptoms. “Then slowly a memory came back, of a description Edward Steichen once gave at a photographers’ meeting of the illness of Edward Weston, ‘dean of photographers,’ who was a Parkinsonian. I remembered the break in Steichen’s voice: ‘A terrible disease… you can’t work because you can’t hold things… you grow stiffer each year until you are a walking prison… there is no known cure…'”

The knowledge was, unsurprisingly, devastating to Bourke-White.

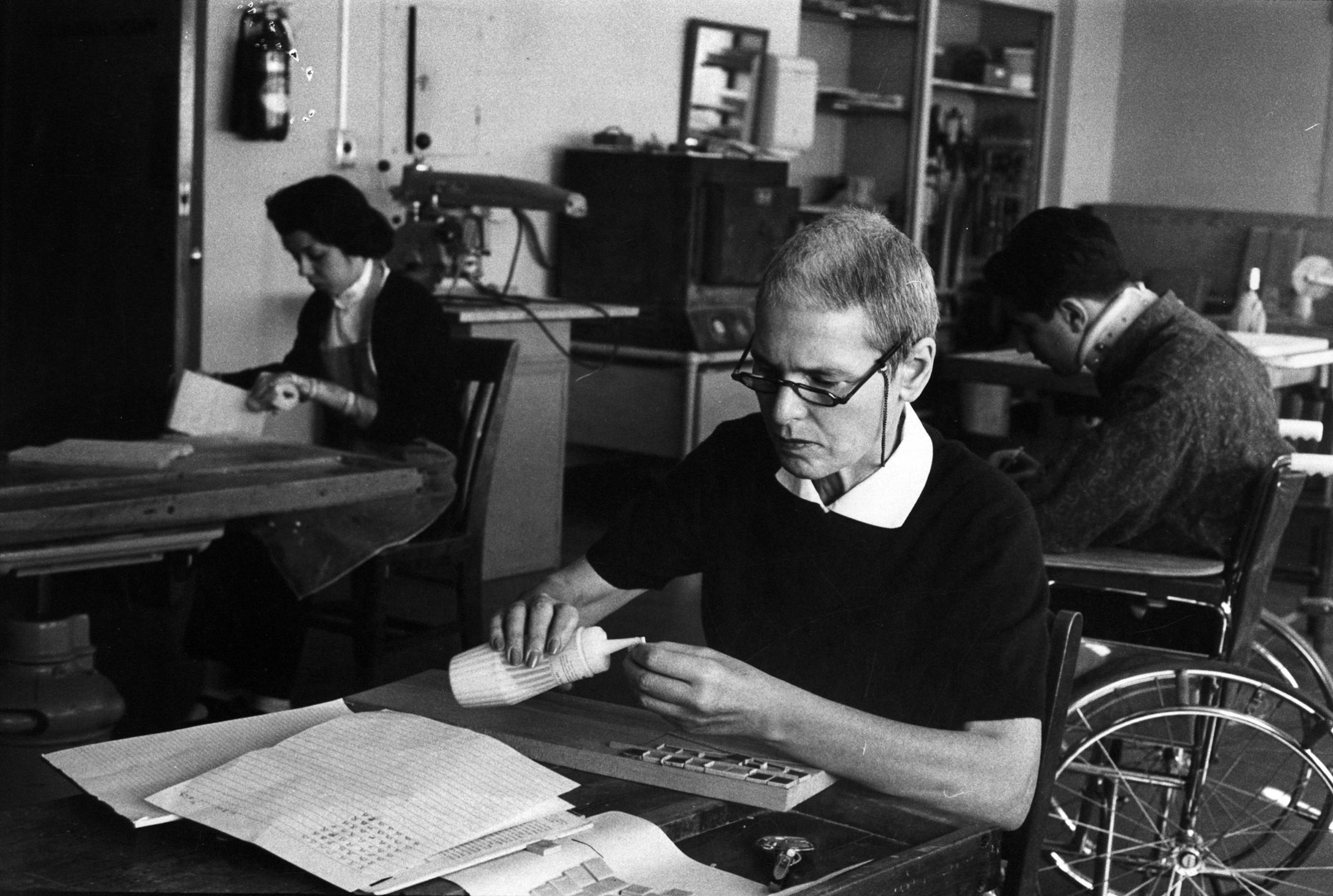

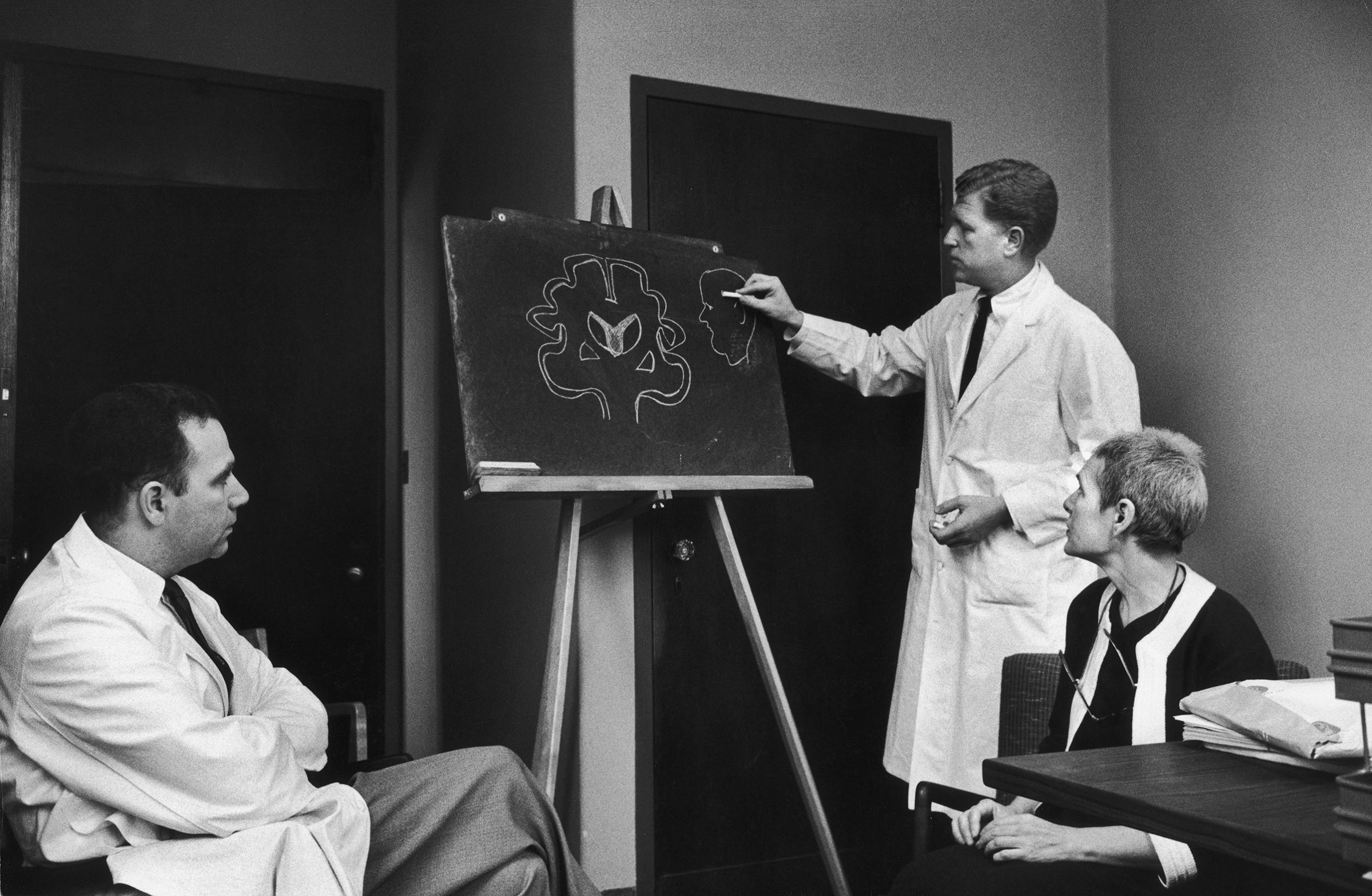

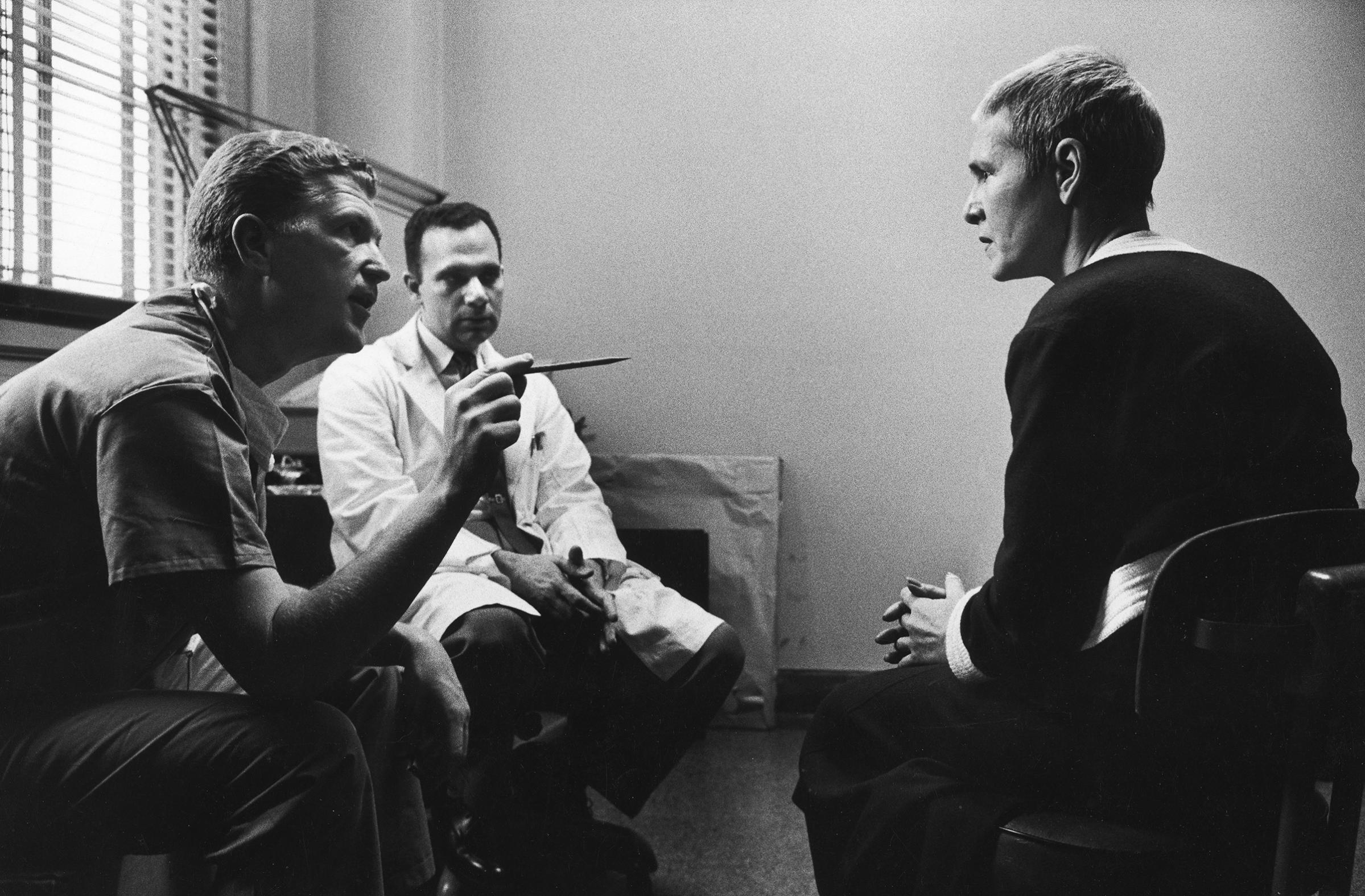

But she set her mind to learn what she could, to look for anything she could do for relief. She learned, she wrote, that she was just one of three quarters of a million Americans with the disease — “often they appear to be struck down at their peak,” she wrote — and that, despite this number and the fact that the symptoms had been observed for thousands of years, nobody knew what caused it or how to stop it. Though Bourke-White was an extreme devotee of her exercise routine and even underwent a then-cutting-edge brain surgery to “deaden permanently” part of her brain, she knew that the operation she’d received had only treated some of her disease and that there was no way to know how the symptoms would progress from there.

Today, more than half a century later, as Parkinson’s researchers and advocates mark 200 years since Dr. James Parkinson described the disease (then known as “shaking palsy”) that would come to bear his name, many of the questions that confronted Bourke-White remain frustratingly unresolved for those who receive the same diagnosis she did. Treatment options, however, have advanced significantly since Bourke-White’s time — and new advances are offering the hope for something even better.

For one thing, says Dr. Rachel Dolhun, vice president of medical communications at the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, a person with Parkinson’s disease in the 1950s had no effective options for medication. The most widely prescribed therapy used today — levodopa, which temporarily addresses some Parkinson’s-related loss of dopamine, a movement-regulating brain chemical — wasn’t discovered until the late 1960s. It is now also understood in a way that it was not a few decades ago that many different brain chemicals and parts of the body are involved in symptoms linked to Parkinson’s, not just dopamine and the brain. In addition, the operation that Bourke-White received to basically destroy part of her brain is largely obsolete today, and a patient who was a candidate for brain surgery now would likely instead receive deep brain stimulation, which uses wires or electrodes to stimulate parts of the brain. (The physical therapy that was prescribed for Bourke-White, however, is one thing that hasn’t changed: exercise remains a key way to address symptoms.)

And Dolhun says that advances in genetic science in the last 20 years or so, by offering new insights into how the disease works, have opened up a new range of research angles — and hope for a real cure, rather than just a better way to address the symptoms. For example, experts are excited by the testing of possible therapies that would target a protein called alpha-synuclein. “Right now, because of those understandings, the development pipeline is richer than it’s ever been,” she says.

Technology is also changing what’s possible for researchers and scientists. The Michael J. Fox Foundation is running an online clinical study in which patients can log on and tell researchers about what it’s like to live their experience of Parkinson’s disease, Dolhun says, and devices like wearables and smartphones are providing new ways to track and communicate about the symptoms. For example, whereas it used to be that a doctor might observe a patient’s tremor for 15 minutes at a time every couple of months, now an app or a watch can allow patients to log data that gives researchers a 24/7 look at information about those symptoms.

These new possibilities are particularly important when it comes to Parkinson’s disease, since the experience of what it’s like to live with and fight the symptoms is very individualized. “It’s a different journey for every single person who’s on it,” says Dolhun. “That’s why we need the patient experience to inform us so much, and that’s why it’s so important for patients to be involved directly in research.”

That’s also one reason why the openness of people like Margaret Bourke-White mattered in 1959 and continues to matter today. There can still be a stigma attached to telling others that you are experiencing something that might make them see you as weak or in need of assistance. But if those who have it keep their experiences to themselves, it’s harder for researchers to make progress toward a cure — and harder for others with the diagnosis to feel that they’re not alone.

For Bourke-White, as she described for LIFE’s readers, her fight against Parkinson’s was, to the fullest extent possible, a reminder to keep working and enjoying what her body could do for every second possible. Nowadays, she wrote in 1959 after the surgery that helped her do that longer than would otherwise have been possible, “my fingers are more and more often loading my cameras, changing their lenses, and turning their winding buttons as I practice the simple blessed business of living and working again.”

“It’s not uncommon for people to feel shy about sharing their stories,” Dolhun says. “For [Bourke-White] to share her story so publicly I think really speaks volumes. When we see people come forward with their story, it’s not an uncommon thing for them to say, ‘I really wish I had shared it earlier.’ They feel a burden lifted.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com and Julia Lull at julia.lull@time.com