Wildlife photographers play a major role in preserving what’s left of our fragile ecosystem – from capturing the effects of climate change on our planet to documenting species on the brink of extinction as they can no longer adapt to the changes that surround them.

The greatest wildlife photographers are highly skilled experts with a deep understanding of animal behavior. For them, the camera is a tool through which their unique experience in the natural world is channeled. As conservationists, they are passionate advocates, often risking their lives to visually record and bring attention to what we are in danger of losing.

As the most significant international agreement to combat climate change took effect on Nov. 4, we asked eight wildlife photographers to select and discuss the images that moved them most.

Michael “Nick” Nichols photographed Serengeti in Northern Tanzania: “Whenever I dream back to this afternoon when I left tracking a pride of lions to follow a family of elephants moving toward life giving rain, I pray that they may forever walk freely. If we lose this, our planet will have an empty heart.”

Steve Winter photographed a mountain lion walking in proximity of the Hollywood sign in Griffith Park in Los Angeles: “I was working on a story for National Geographic on mountain lions, and I asked the scientist, Jeff Sikich from the National Park Service in the L.A. basin if they had any cats that walked on trails where you could see the Hollywood sign. He looked at me like I was crazy and said, ‘No, not now.’ I asked him to let me know if things changed.

Eight months later, I received a text from Jeff saying ‘Call me, NOW.’ They had just gotten a trail cam image of a cougar in Griffith Park! This cat named P-22 had successfully crossed some of America’s busiest freeways to reach Griffith Park in Los Angeles. Because we increasingly live with wildlife in urban settings, I was determined to photograph him.

The National Park Service had outfitted him with a GPS collar I had bought with a grant from the Nat Geo Expedition Council to track his movements so I set up ‘camera traps’ along trails he walked. It took 15 months to capture this image. When the story ran and people learned a mountain lion was essentially stranded in Griffith Park, it sparked huge media attention, including a front page story in the L.A. Times and a segment on 60 Minutes.

P-22 has become the poster child for wildlife that needs to move between protected areas, and his plight has brought together nonprofits, government and the public in an initiative that will build California’s first wildlife overpass bridging the 101 freeway at Liberty Canyon, which will be the largest in the world. This image means a lot to me because it made a difference.”

Ken Geiger photographed the Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming: “There is something deep inside me that needs solitude, that needs quiet, that needs nature, trees, animals. There is something inside me that needs to escape from humanity because I care too much. I’ve seen too much war, death, pain and tragedy. I’ve seen it in person, I’ve seen it in pictures, I’ve seen it on the front page. I’m one of the ones responsible for putting it there. I’ve watched a medic scoop a man’s brains back into his smashed skull, load his lifeless body into an ambulance knowing there was no way he survived. So many memories haunt my mind. What privilege it would be to have no care, to be a bison in the primal landscape of Yellowstone to just exist and be part of the texture of real.”

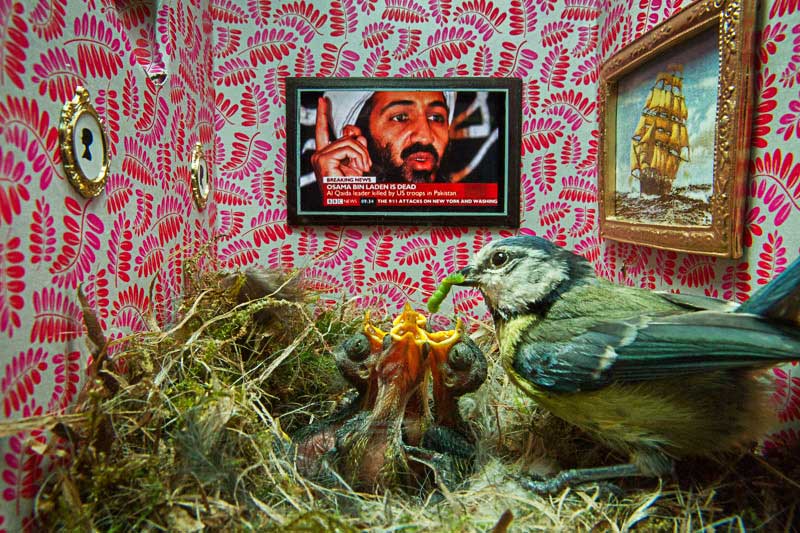

Charles Hamilton James photographed a mother European blue tit feeding her young in what he calls the “Osama Nest”: “This picture is meaningful to me because for the first time, it made me realize the true absurdity of human beings. I took it years ago. I was trying to get a shot of the Royal Wedding in the U.K. on the screen in the background. The screen is actually my iPhone streaming live news, but I dressed it as a flat screen TV on the wall. I missed the Royal Wedding as I wanted to redecorate the nest box. Instead, I got the death of Osama Bin Laden. It struck me as odd. It’s the only picture I’ve ever named. I hate naming pictures because I think it’s cheesy and is generally done to add gravitas to a picture so I named it ‘Innocence is Beauty.’

Assuming that everyone would think we’d faked it, we shot a video to accompany it. Luckily, I have spent my life working with animals and became an expert at putting cameras in bird’s nests, so I pulled this off without disturbing the birds. All those chicks fledged happily. I’m sure when they came to build and dress nests of their own, they would have struggled with the decor. You don’t often see birds flying in to dress their nests with miniature pictures of the Spanish Armada.”

Brian Skerry photographed a seal pup being aided by its mother to get back on stable ice: “A harp seal pup, about five to seven days old, had fallen through thin ice. Its mother frantically trids to help the pup up to breathe and to get back on stable ice. These pups require stable ice so they can nurse from their mothers. Climate change in recent years has produced thinning ice and some years, no ice at all, which is a serious problem leading to high pup mortality rates in Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Making this picture affected me greatly since I had never seen such a scene before and I felt it was likely the beginning of many troubling further climate scenes I would witness in the time ahead. I was in this place to document the life cycle of these animals and to cover the issues surrounding the hunting of seal pups. But came away realizing that the loss of sea ice would be the real game changer for this specie.”

Joel Sartore photographed the world’s last Rabbs’ fringe-limbed tree frog: “What’s the most meaningful picture I’ve taken to date? It has to be this portrait of the world’s last Rabbs’ fringe-limbed tree frog. He died a couple weeks ago, and his species is now extinct.

Named ‘Toughie’ for the fact that he hung on in captivity for more than a decade, this little guy was an inspiration to me and many others who care about conservation. We now vow to tell his tale as often as possible, along with the stories of so many other species on the very brink of extinction. After all, as they go, so do we. ‘This time,’ we say to ourselves, ‘the world will finally wake up and care about something other than Kim Kardashian’s rear end.’ After all, the future of life on Earth depends on it.”

Brent Stirton photographed Tuareg people working in the banks of the Niger River: “Tuareg men plant grass in the banks of the Niger River to grow a forage crop for their animals and to sell in the markets in the sedentary Tuareg village of Dag Allal in Mali. Unusual amongst Tuareg for their sedentary, non-nomadic existence, these Tuaregs farmers remain in place all year and care for their animals by utilizing agricultural techniques. They grow rice and forage grass in the nearby Niger river, using a canal and small pump to divert water into rice paddies.

Their leader, El Hadg Agali Ag Mohammoud, 70, explains that a new pattern of drought has caused this group to choose to remain in one place. ‘We live here all year. We take care of our animals by growing the grass that they wouldn’t normally have in the hot summer months. Other Tuareg don’t always understand this as they think that this grass grows naturally. We sometimes have to prevent them from taking it. We have to explain that we grow it for our animals and it is not free. Sometimes, there is confrontation as a result. This is not the traditional Tuareg way so we have to explain it to them.’

I think in the future, there will be more Tuareg living this way.”

Cristina Mittermeier photographed this Inuit hunter in the remote village of Qaanaaq in Northern Greenland: “As I watched Naimanngitsoq Kristiansen, a traditional Inuit hunter, stand at the edge of the sea ice, I was reminded that for most of us climate change is still a theoretical problem. Naimanngitsoq and his people are the last hunters of the North, and for them, climate change is very real.

As the ice melts literally beneath their boots, they are losing not only the icy highways on which their dogsleds travel. But, they are also losing an entire, and ancient, way of life. Honed over thousands of years to survive and thrive in the icy ecosystems of the north, the Inuit people will be some of the most dramatic and tragic victims of climate change.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com