Church bells rang in the small towns of Colombia at 12:01 a.m. on Aug. 29. The tolling marked the official start of a cease-fire that was years in the making and the end of a war that had dragged on for decades. The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia–a Marxist guerrilla group known as FARC–and the Colombian government had agreed to stop fighting, the first step toward the disarmament of thousands of FARC troops and the end of the longest-running war in the Americas. Since it began in 1964, the war had killed roughly 220,000 people. “Never again will parents be burying their sons and daughters killed in the war,” said Rodrigo Londoño, FARC’s leader, known in Colombia by his nom de guerre Timochenko.

But those bells weren’t ringing just for Colombia. The formal end of the conflict marks the effective end of war in the western hemisphere, home to more than a billion people. There is still plenty of violence to be found in the Americas–especially drug-related gang violence in countries like Mexico and Honduras. But traditional armed conflict–involving armies from two or more states, or between a government and an organized rebel group–has ended on one-half of the planet. At a moment when much of the world feels out of control, that’s worth celebrating.

It’s fitting that the war with FARC should be the hemisphere’s last, as it set the template for conflicts that would plague the region during the Cold War and beyond. The group was founded by Pedro Antonio Marín, a peasant farmer who went by the moniker Sureshot, and it sought the redistribution of land to Colombia’s agrarian poor. It wasn’t long before the group was adopted by the Communist Party of Colombia as its armed wing, making it one of a series of far-left rebel groups that flourished in Latin America: Peru’s Shining Path, Argentina’s FAR, Nicaragua’s Sandinistas in the 1970s and ’80s. Those were the years when Latin America was the hot front of the Cold War, with the Soviet Union and the U.S. each backing their ideological allies in the jungles.

Later, FARC, like many other rebel groups in the region, branched out into crime, financing its growing operations through drug trafficking and kidnappings for ransom. At its height, FARC boasted 18,000 guerrillas and was strong enough to threaten the capital, Bogotá. But paramilitary groups and the Colombian army–which became one of the largest recipients of U.S. military aid–were able to fight back. FARC’s active troops number fewer than 7,000 now. Colombians paid the price, though–80% of the 220,000 people killed during the war were noncombatants, and both sides were accused of serious human-rights abuses.

It took years for the cease-fire to be negotiated between FARC and the Colombian government, and even now peace isn’t a certainty. While FARC fighters will begin to hand over their weapons to U.N. observers, Colombians will need to approve the deal in a plebiscite on Oct. 2. Approval isn’t guaranteed; many Colombians are angry that FARC fighters won’t face harsher justice for crimes committed during the war. And reintegrating FARC guerrillas–many of whom have been living in the jungle for decades–into Colombian society won’t be easy. But ask the people of Syria if they’d like a chance to vote on peace, however compromised.

Latin America today is hardly perfect, but it enjoys a level of peace and prosperity unimaginable during the years of the Cold War. Military coups are largely a thing of the past; democratic governments are increasingly the norm, and even longtime enemies like the U.S. and Cuba are growing closer. (Just two days after the FARC cease-fire began, scheduled passenger-jet service between Miami and Havana restarted for the first time in more than 50 years.) In this, Latin America is following the example of once war-torn regions like Southeast Asia that are now almost entirely free of active combat. That should give hope to people in the regions of the world–chiefly the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa–still blighted by war. Those bells may ring for them one day.

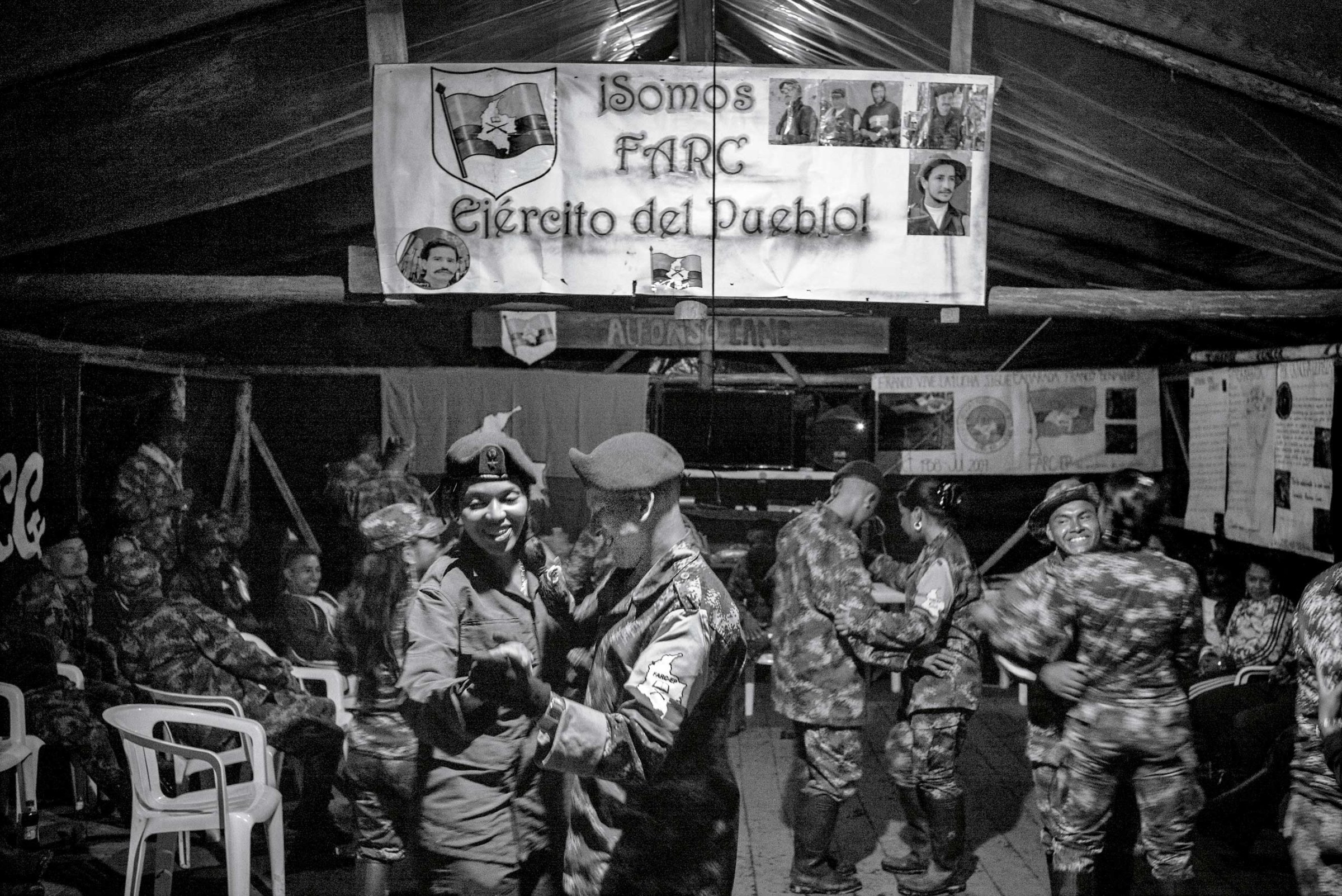

Life in FARC

Photographer Alvaro Ybarra Zavala was able to make rare visits to remote FARC camps in March and July as the guerrillas warily prepared for peace.

CIVILIANS

A group of Colombians wait for a Christian Mass to begin in the village of Puerto Camelias. The area is under the effective rule of FARC and has been a major source of coca crops. But as the peace process has continued, the cultivation of coca has ended–and the population of the village has fallen rapidly.

GUERRILLA LIFE

A member of FARC cuts the hair of another soldier in a camp. The group still dominates life in some parts of rural Colombia, where it has effectively displaced the government. Many of the soldiers are teenagers who have spent nearly all of their lives with FARC. Reintegrating into civilian society, should peace hold, will be a challenge.

THE WOMEN OF FARC

A FARC member puts on makeup in a jungle camp. Female soldiers are not uncommon in FARC, but the rules forbid marriage within the group, though intimate relationships are allowed.

MEMORIALS

A child in the FARC-controlled community of Guama waits at the door of his house. The drawing on the pillar is of Alfonso Cano, the top commander of FARC until he was killed by the Colombian army in 2011. It wasn’t until after Cano’s death that peace talks between FARC and the government took off, eventually culminating in the Aug. 29 cease-fire.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com