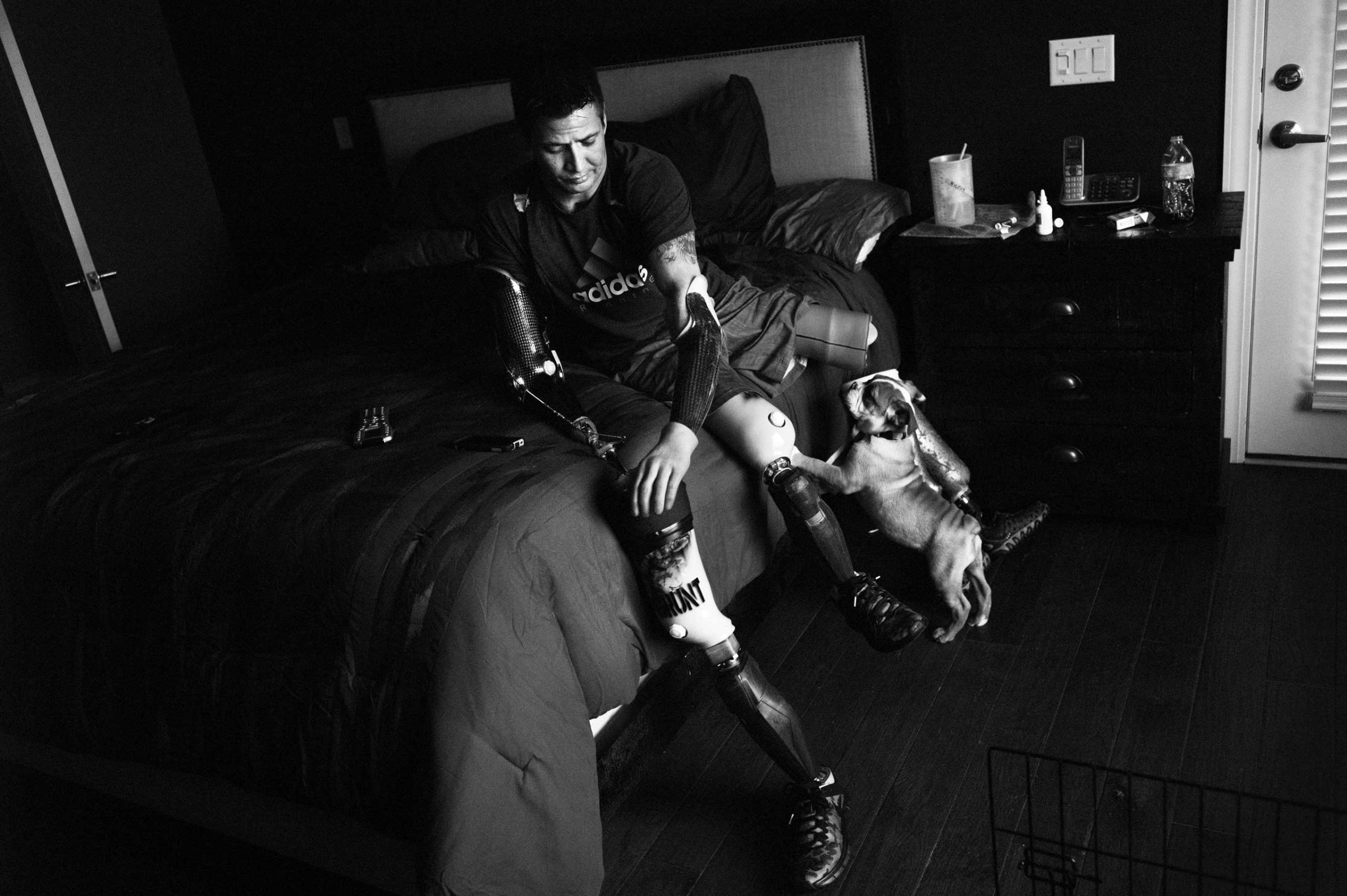

Corporal Todd Nicely has at least three pairs of legs and four sets of hands. He wears them intermittently as they suit his needs, and replaces them when the fragile central machinery breaks, the grip frozen into a tight fist, the fingers too loose to hold. He is slightly taller than his original height when he wears the longer carbon fiber limbs; and roughly 11 inches shorter with the smaller legs he uses to drive.

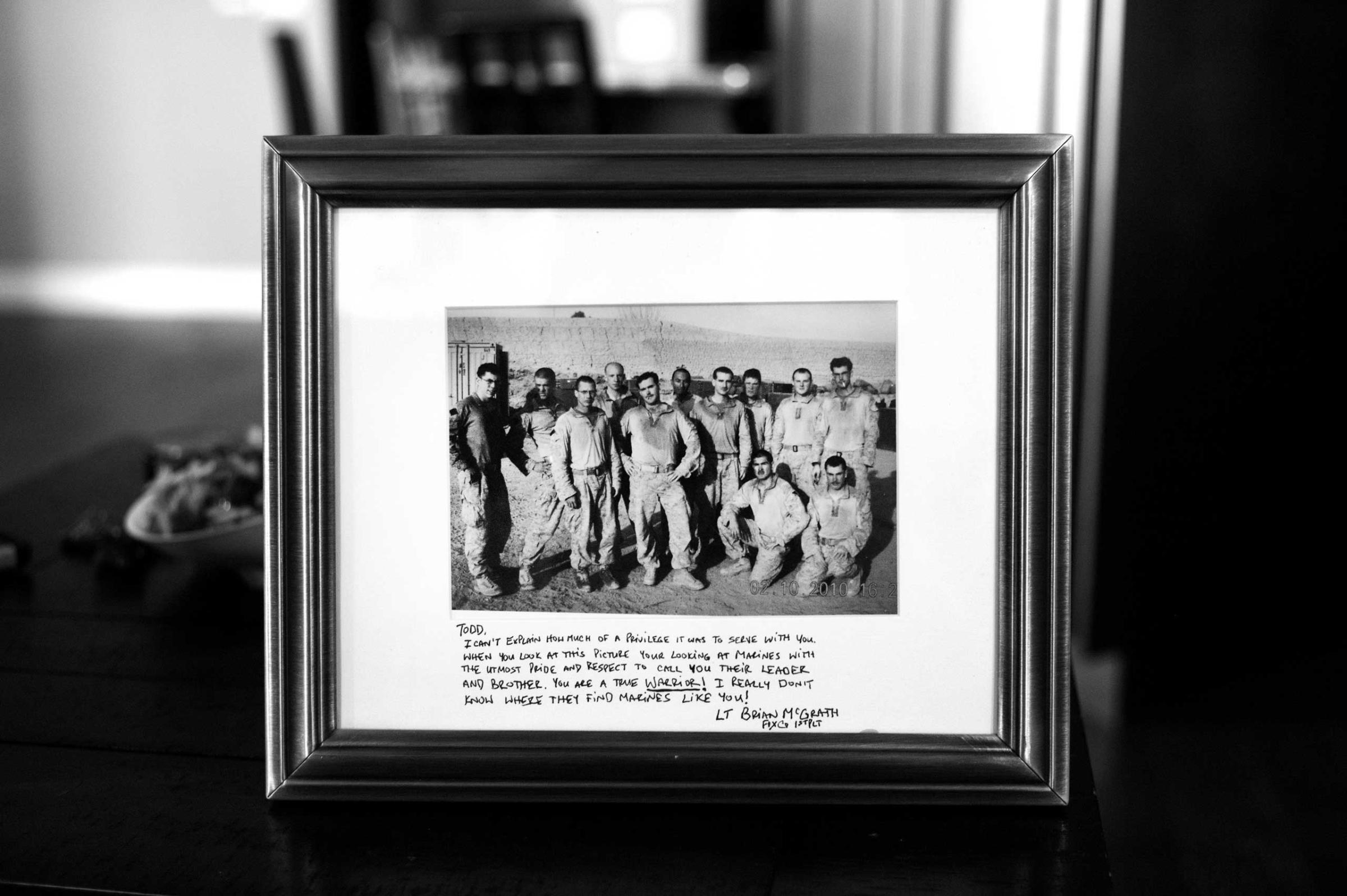

Nicely was 26, a young corporal leading a squad of 12 infantry Marines on a security foot patrol in Lakari, the southern province of Afghanistan’s Helmand, when he stepped on an improvised explosive device. The terrorist attacks that struck his country nine years before had prompted him to join the infantry on the front line. Rising through the ranks quickly in what was a rewarding military career, his service came with a high price: he lost both legs above the knee, the right arm at the elbow, the left one at the wrist. A quadruple amputee, he has no regrets.

“[Life] is good,” he says over the phone from his smart home two foundations – the Tunnel to Towers Foundation and the Gary Sinise Foundation – built for him in Lake Ozark, Miss. The house was designed to meet his needs with customized features: an indoor elevator, touch-sensitive faucets, and adjustable-height kitchen cabinets where door handles and levers substitute for knobs. “Everyday is the same now, I get up in the morning, and time flies,” he says. “I’m just trying to find something new to do everyday.”

Since day one, corporal Nicely has sported an enduring fortitude that has sustained him through the worst moments and inspired his peers throughout their lengthy recovery. Interested in covering veterans, Italian photojournalist Federico Borella wanted to know how regular life resumes after such a traumatic experience; how a person who has suffered this type of injury accepts and recovers from the loss.

“For me it has always been particularly difficult to understand fully the fact that someone goes to war, goes to the frontline and puts his own life at risk for his home country,” Borella says. “This was always something that stung my curiosity, and I have often wondered if I would be able to do the same.”

In 2013, Borella contacted Nicely through Facebook with a simple message asking to document how the marine approached his life day by day. “I didn’t know how much time he would have granted me, if the overall feeling was going to be right… But that was also the beauty of it, to discover things step by step, discover that we are actually very similar.”

Borella entered Todd’s daily routine gently but firmly. The two men bonded quickly as they were of the same age and had common tastes: combat video games, rock and metal music, Limp Bizkit and Eminem. The photographer visited Nicely twice over the stretch of two years, both times for about two weeks: in April 2014, he lodged at a motel a few miles from Nicely’s house; and a year later, around Memorial Day, he stayed at the marine’s place. The two would drive around Lake Ozark, and Nicely would play the songs he used to listen to in Afghanistan to pump himself up before a patrol.

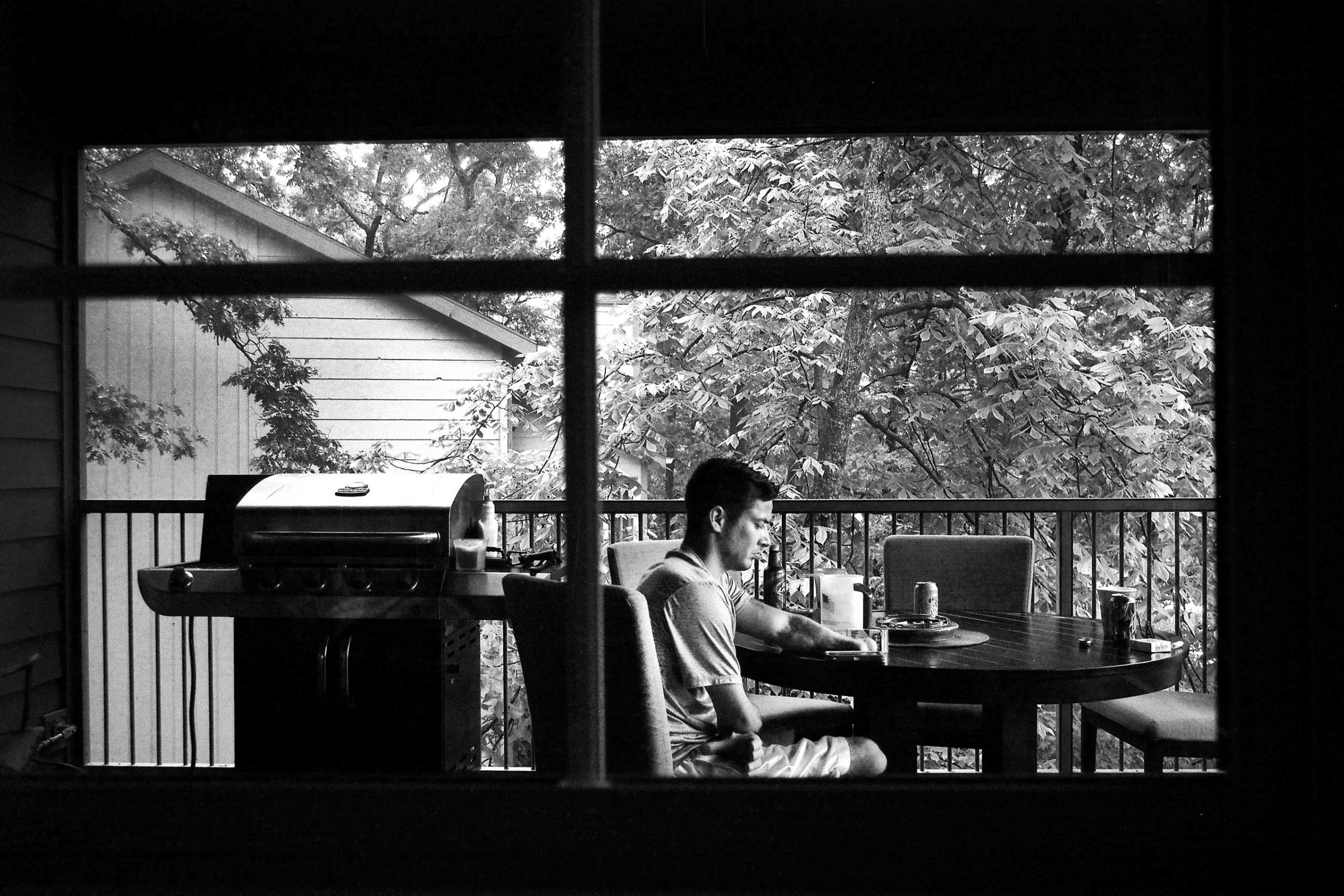

During his first visit, Borella captured quiet moments of privacy and solitude, portraying the corporal mostly by himself, but he began to feel that his photos weren’t doing justice to an important aspect of Nicely’s days – namely, his social life – as relatives, friends, his girlfriend, colleagues and often many dogs, congregated at his place.

As time progresses, Nicely’s routine life has improved slowly but steadily. He enjoys boating when the weather warms up on the lake near his house, he says. He travels often, both for pleasure and to attend charity events, raising money for other injured vets. After divorcing his wife over a year ago, he has also embarked on a new relationship. “It is just a never-ending process of relearning how to do things,” he says. “Something that I couldn’t do a year ago I am doing by myself now.” Recently, he has started to relearn how to drive his car using his artificial feet and legs, instead that solely with the arms’ prosthesis.

“I was there to document his rebirth,” the photographer emphasizes, “and at the same time the fact that [Nicely] is and always will be a marine.” What emerge in Borella’s pictures is not only the fierce fortitude and obstinate endurance of a soldier but also the natural temperament of a simple man, moving with confidence into his new life, learning everything anew – how to shave, how to shower, how to light a cigarette – without losing will or hope.

As Nicely’s wounds and limbs fade into the background, subtler, emotional moments come into focus: the occasional reserved distance shown by the corporal even when surrounded by friends, or his youthful tenderness when glancing at his mother as she lights candles on a cake. Moreover, Borella was struck by the willpower that Nicely practiced since the accident. A message reiterated by the corporal over the course of the years. “If [the photos] can inspire just one person to get up and try something, then I think they have done their job,” says the quadruple amputee with optimism and determination.

Federico Borella is an Italian photojournalist based in Bologna, Italy. See more of his work on his website.

Mikko Takkunen, who edited this photo essay, is the International Photo Editor at TIME.com. Follow him on Twitter @photojournalism.

Lucia De Stefani is a writer and contributor at TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Follow TIME LightBox on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com