Cormac McCarthy, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of often grisly, hypermasculine fiction died Tuesday at 89, in his Santa Fe, N.M. home. One of the most acclaimed—if reclusive—American writers of the last 50 years, McCarthy’s dark and devastating fiction centered on outsiders attempting to survive their often violent worlds. McCarthy, who was born in Providence, R.I., and raised in Knoxville, Tenn., wrote a dozen novels during his career, beginning with his 1965 debut The Orchard Keeper, a haunting tale of a young boy and a bootlegger in rural Tennessee. The 1981 MacArthur fellow, who was hailed by the foundation as the author of “distinctively American fiction in the southern gothic and epic western traditions” also wrote several screenplays, short stories, and plays.

Here, the essential books to celebrate and understand McCarthy’s contributions to the literary canon.

Blood Meridian (1985)

Violence is the seeming lifeblood of Blood Meridian, McCarthy’s fifth novel, which is a macabre epic of the American West. Published in 1985, it centers on the harrowing experiences of a ruthless runaway known only as “the kid.” McCarthy’s protagonist comes of age as part of the Glanton gang, a group of outlaws who were notorious in the mid-19th century for murdering Indigenous peoples across Texas and Mexico. The result is a nightmarish fever dream of gang violence and robberies, scalp hunting and cold-blooded killings—one that disrupts any heroic or romantic fantasies of the frontier.

All the Pretty Horses (1992)

In 1992, McCarthy published his first popular novel, the National Book Award-winning All the Pretty Horses, the story of two men, John Grady Cole and Lacey Rawlins, who head off on horseback on a journey from Texas to the U.S.-Mexico border. There, the aspiring cowboys find a ranch where their skills give them purpose—and where one of them finds love. It’s a beautiful, heartbreaking novel, suffused with McCarthy’s deep sense of the landscape and some of the apocalyptic overtones that showed in his earlier fiction and would define his later work. In this mid-career high point, McCarthy delivered a true American classic, one that will stand for decades.

No Country for Old Men (2005)

McCarthy originally wrote his 2005 novel No Country for Old Men as a screenplay, which might explain its more streamlined prose, a departure from his usual writing style. But he trod familiar territory with a brutal tale that excavated the dark side of the American West. This spare yet disquieting thriller of a novel, which was adapted into a film that won Best Picture at the 2008 Academy Awards, delves into the gruesome aftermath of a drug deal gone wrong at the Texas-Mexico border in the 1980s. Centering on a chilling and murderous chase between a Texas sheriff and a sociopathic killer, the novel is an unflinching exploration of violence, isolation, and masculinity.

The Road (2006)

In McCarthy’s haunting, Pulitzer Prize-winning 2006 novel The Road, death looms large as a father and son struggle to survive in an ash-covered, post-apocalyptic America. Traveling by foot bearing just a revolver with two rounds for protection, the stoic pair endure the ravages of nature while fending off marauders and cannibals in their desperate bid to stay alive. Though The Road may be one of the bleakest tales McCarthy wrote (and that’s saying something), there’s an element of tenderness in his depiction of the fierce love shared between the nameless father and son, which provides a sustaining force in a devastated world.

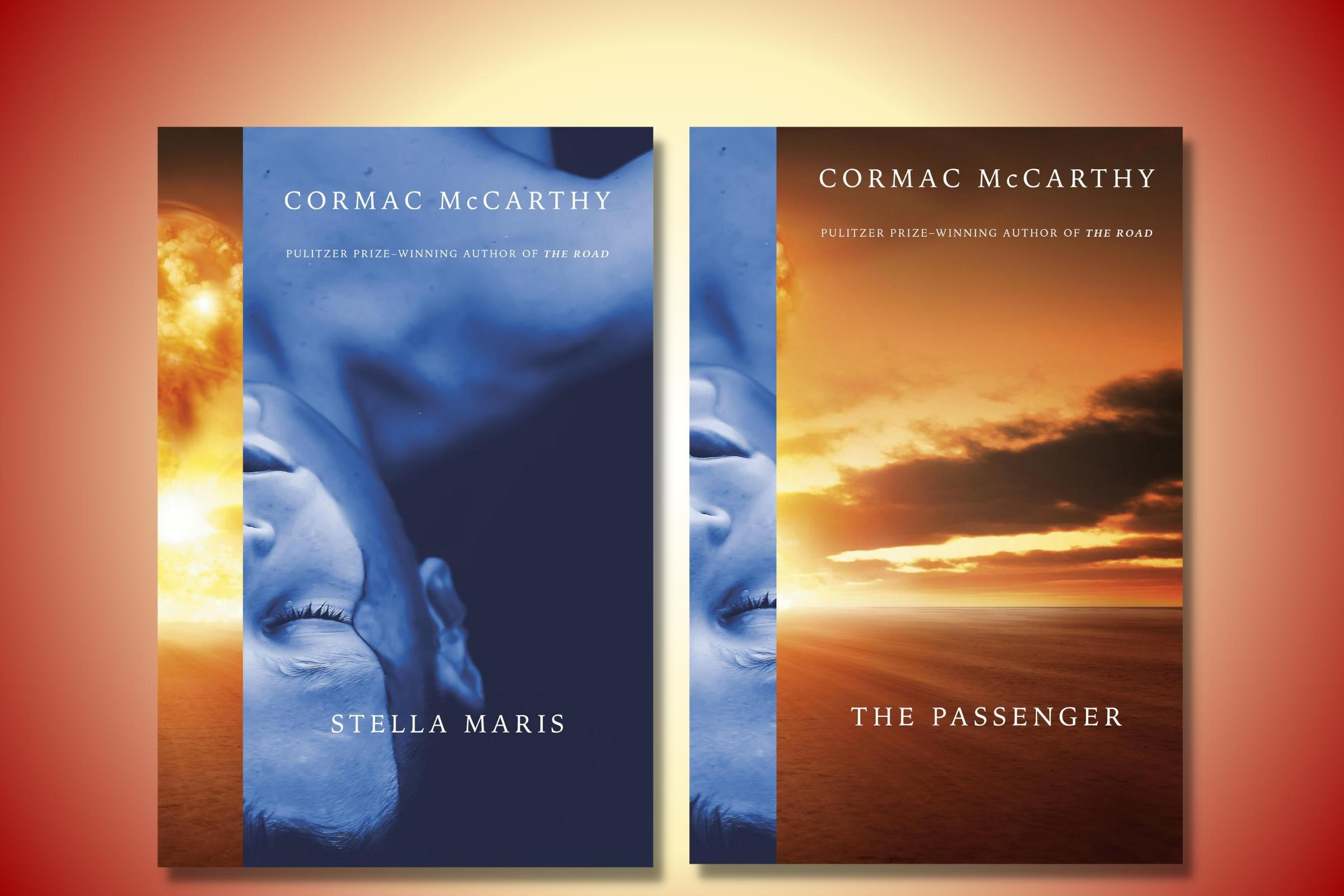

The Passenger and Stella Maris (2022)

In 2022, McCarthy published his final novels, a companion set: The Passenger and Stella Maris. Both books, which were his first since The Road in 2006, tackle grief, longing, and loss. In The Passenger, a 37-year-old salvage diver discovers a sunken jet in the deep sea that is swirling with mystery. The diver is also haunted by the death of his younger sister, a math prodigy who died by suicide. In Stella Maris, McCarthy tells the sister’s story, focusing on the young woman as she contemplates her life while in a psychiatric facility. Nicholas Mancusi wrote in his review for TIME: “Like Bach’s concertos, these triumphant novels depart the realm of art and encroach upon science, aimed at some Platonic point beyond our reckoning where all spheres converge.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Annabel Gutterman at annabel.gutterman@time.com and Cady Lang at cady.lang@timemagazine.com