In the fall of 1968, journalist Earl Caldwell had just gotten back to the New York Times‘ offices in New York City from a reporting trip in California. As he recalls, he was at his desk for no more than five minutes when a receptionist told him that two men were at the office and wanted to speak with him. They were with the FBI.

The agents wanted to know more about a story Caldwell had just written for the Times on the Black Panthers and their weaponry. Caldwell had only recently been assigned to cover the Panthers for the Times; the piece in question was his first article on the group. The agents told him that they wanted more information about the guns he had written about—and more insight into the Panthers in general.

“I knew this was the beginning of something real,” Caldwell tells TIME of the meeting, in which he told the agents that everything they needed to know was in the newspaper. A year and a half later, he received a subpoena to appear before a federal grand jury and testify about all his knowledge on the Panthers, including confidential sources.

By that point in his career, Caldwell had already established himself as a trailblazer for Black journalists.

He was the only reporter at the scene in Memphis was Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated on April 4, 1968. King’s murder came during Caldwell’s first assignment embedded with him; this was also the first time the Times had sent a Black reporter to cover the civil rights leader.

“[I told my editor] I didn’t want to be in the South,” Caldwell remembers, citing the region’s well-documented history of racial prejudice and violence, “but I also didn’t want to pass up an opportunity to cover King. It was surreal being there and seeing all of this unfold.”

After King’s assassination, Caldwell went on to cover the race riots that ensued across the country for the Times. It was during this time that he started covering the Black Panthers, focusing on their San Francisco chapter. He spent over a year reporting on the organization based in California.

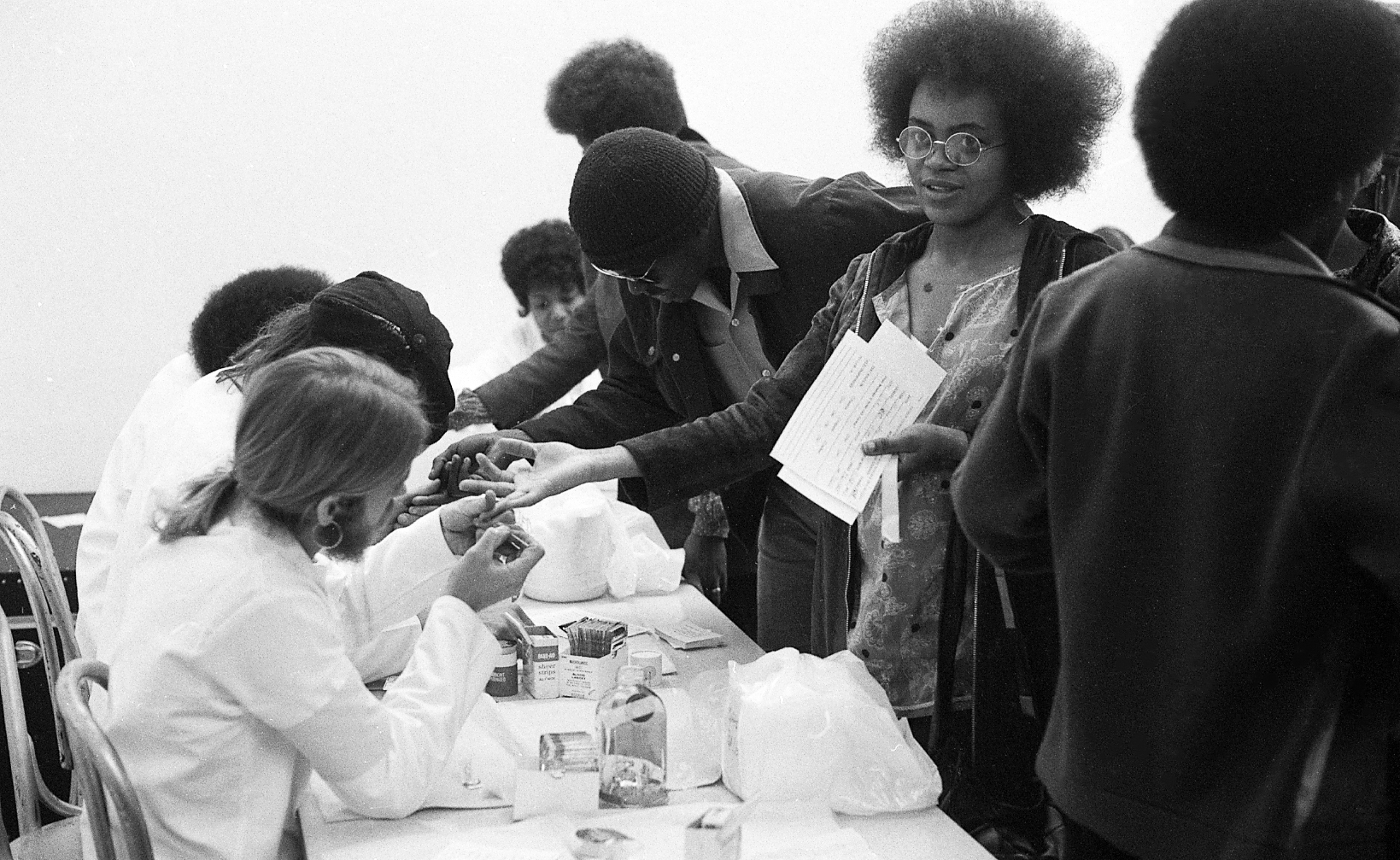

“The Panthers were really good at getting their message out there,” Caldwell says. “They gave me good access because they wanted people to know what they were about.” He covered a wide range of stories about the Panthers, including their outreach work, clashes with law enforcement and confrontations with other Black nationalist groups.

“I really got in good with them and was proud of the stories I was able to tell,” he says.

Read more: Black History Lives in Memories and Minds. COVID-19 Has Endangered Those Traditions

However, as Caldwell’s reporting on the Panthers deepened, so did the FBI’s interest in his work. The agency continued to request meetings with him, with a view to sourcing information about the group; they tried to persuade him that Panthers were dangerous.

Caldwell stood his ground and refused. According to a 2006 interview with Frontline, Caldwell says that the Times hired a law firm to defend the news organization but he soon grew concerned about the firm’s position on his case, as he came to understand that they were considering handing some of his information over to the FBI. Caldwell says there was no way he was going to be a spy for the federal government. “It goes against everything you stand for in journalism,” he adds.

So when Caldwell received the FBI’s subpoena, he consulted with other Black journalists and eventually sought counsel from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund who put him in touch with constitutional lawyer Anthony Amsterdam. On his own accord, he refused to appear before the grand jury—and Amsterdam appeared for him. He argued that he should not have to appear and that the First Amendment protects sources and information as well as the reporting process. Amsterdam also argued the importance of Black journalists’ work, and “how we could bring back an answer and tell America about these questions that were so large at that time,” Caldwell recalled to Frontline.

The case made its way to the United States Court of Appeals, which ruled in Caldwell’s favor and agreed that he did not have to share his confidential information with the federal government. It was a short-lived victory, however, as the government appealed the case to the Supreme Court, and was taken up by the Court in combination with two other First Amendment cases in February 1972.

These other two cases involved Paul Pappas, a Massachusetts television reporter who was also covering the Black Panthers and had also refused a subpoena to give information on them to local law enforcement, and Paul Branzburg, a reporter for the Louisville Courier-Journal who had been covering the manufacturing of the drug hashish (or hash). As part of his reporting, Branzburg had interviewed people who had made the drug but did not reveal their identities in his stories—and, like Caldwell and Pappas, refused to do so after being called to a grand jury by law enforcement officials.

In the court’s eventual Branzburg v. Hayes ruling, which dropped on June 29, 1972, the Supreme Court ruled against the reporters. In the majority opinion, Justice Byron White wrote that it was inappropriate “to grant newsmen a testimonial privilege that other citizens do not enjoy.” But the justices were split 5-4 on the issue, with those in dissent arguing that the government does not have a right to use the media to do its job for them.

“The case had a fairly large impact on the journalism field because it meant that journalists do not have special protection,” explains Robert Richards, a media law professor at Penn State. “They weren’t looked at as having more privilege than the average citizen when it came to grand jury testimony.”

The decision meant there was a possibility that Caldwell could go to jail, but the federal government never pursued him again. He continued to work at the Times, covering the 1970 trial of Angela Davis, the “Atlanta Child Murders” and Rev. Jesse Jackson’s 1984 run for president. In 1979 he became the first Black journalist to have his own column at a major newspaper, having moved to the New York Daily News.

“He really did some amazing reporting throughout his career. If you read his stuff, it’s very cinematic,” Wayne Dawkins, a former reporter and colleague of Caldwell’s at Hampton University. “He set a standard for a lot of us.”

Read more: The History Behind the First Black Woman Supreme Court Justice Nominee

Caldwell’s case, though not the most well-known, was a very significant case for journalists and First Amendment rights.

“After this case, there was a movement throughout the U.S. to create shield laws to protect journalists,” Richards says. (At least 40 states have laws of this kind in place.) “I think the concern is how you define a journalist, especially today. A lot of states define it differently.”

“While smaller court circuits have taken care in balancing the reporter’s privilege with compelling subpoenas, journalists haven’t had as much success in the federal courts,” a 2012 Indiana University analysis of the Branzburg v. Hayes ruling argued. “Today, media has evolved to include the Internet and ‘journalist’ is not so easily defined. Thus, recognizing a reporter’s privilege in an age when reporting is commonly accessible demands a more nuanced interpretation.”

Caldwell’s stance to protect the Black Panthers and stay true to his responsibilities as a reporter is particularly relevant—and resonant—in the context of the racial reckoning America has faced in recent years. For Caldwell, his role as an objective observer of the Black Panthers did not diminish the fact that he was a Black man in a racially divided country that needed to address its systemic issues.

“These are Black people arguing for Black rights… It’s just like Martin Luther King Jr. He’s up on that platform talking about the rights of Black people,” Caldwell told Frontline. “I can’t separate myself from that because I’m Black, and he’s talking about my rights. I’m a reporter. But reporters are human beings, so we’re faced with these same things every day.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Josiah Bates at josiah.bates@time.com