The Biden Administration announced its plan to return to an Obama-era initiative to put Harriet Tubman’s face on the U.S. $20 bill. Her image would replace Andrew Jackson, the notoriously racist President, known both for owning hundreds of slaves and for his brutal and genocidal policy of Indian removal. Based on current designs, a statue of Jackson would remain on the back of the bill, while Harriet Tubman would grace the front. Many Americans, across the racial spectrum, are excited about this tribute to Tubman. They view it as progress, as a necessary and long overdue disruption of the American Founding Fathers narrative. I do not.

I know in a country that worships at the altar of capitalism–an economic system made possible by the free Black labor procured through the Transatlantic slave trade–a Black woman’s face on our currency seems like the highest honor we could bestow. But what a stunning failure of imagination. Putting Tubman on legal tender, when slaves in the U.S. were treated as fungible commodities is a supreme form of disrespect. The imagery of her face changing hands as people exchange cash for goods and services evokes for me discomfiting scenes of enslaved persons being handed over as payment for white debt or for anything white slaveholders wanted. America certainly owes a debt to Black people, but this is not the way to repay it.

On the heels of Kamala Harris’ historic ascension to the Vice-Presidency, questions about the politics of representation figure heavily in our political discussions and calculations. I believe that representation matters, that it matters for a woman (with liberal values) to be president someday, that Black people and people of color should be in positions of leadership and decision-making in our government. But all forms of representation are not equal, and the desire to put a Black woman’s face on our currency represents a narrative of diversity and inclusion that is deeply ahistorical. It is the ignominious relationship of Black bodies to capital and currency that is the cause today of our most violent battles in this country.

Consider that just weeks ago, an angry insurrectionist white mob stormed the U.S. Capitol, carrying, among other items, the Confederate flag. American lore suggests that the Confederate flag had never previously entered the U.S. Capitol, even during the Civil War. I say lore because we all know that even if the symbol of the Confederacy had never been in the Capitol, Confederate ideas have found a hearty welcome there both in the past and in the present. Since this history has violently reinserted itself, demanding our attention, and if we are wise, our reckoning with a racist past that is never quite past, then we should note, that Black people’s faces have, in fact, been on our national currency before. During the Confederacy, as each secessionist state printed its own money, images of enslaved people picking cotton and doing other forms of menial labor appeared on the currency in several states.

The default position in America is that Black bodies are only useful insofar as they turn a profit. We fought a bloody war over this issue. And then the country turned around and built a prison system based on exactly the same premise, hence calls to abolish prisons, which depend in most cases on a massive amount of free Black labor to turn a profit.

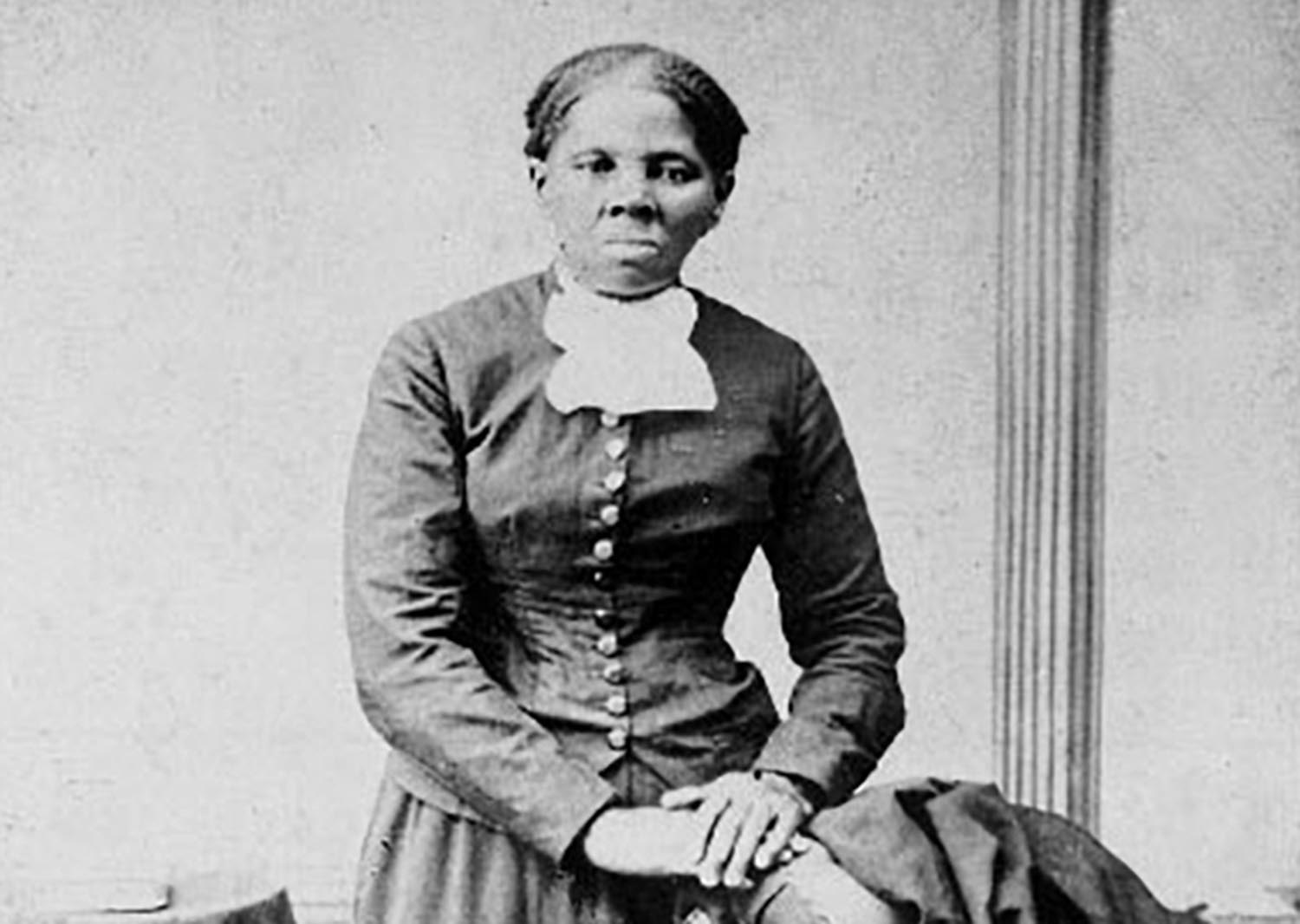

Harriet Tubman’s life was about fighting against the system that treated Black lives and Black bodies as property, currency and capital. She was a great emancipator, freeing herself and hundreds of others and helping to bring the Union forces to victory working as spy in South Carolina during the Civil War. Would she consider it an honor to have her likeness plastered on American currency? And if she agreed to the honor, what would she ask for in return?

Nothing short, I am sure, of broad structural change together with specific and targeted systemic interventions to aid Black women and Black communities. A 2015 report placed single Black women’s median net wealth at $200; it placed Black men’s median wealth at $300. Nearly a quarter of Black women live in poverty. And we know that Black women are disproportionately represented as essential workers. (Our Latina sisters often fare worse.)

If Tubman is going to be linked to conversations on capital, that conversation must be about a redistribution and funneling of resources and money into Black communities, to deal with wealth and wage disparities, access to education and safe housing, and a comprehensive plan of action to redress the social determinants of poor Black health. Anything else is downright disrespectful. Perhaps we need the Harriet Tubman Reparations Act or the Harriet Tubman Abolition of Prisons Act. What we don’t need is Harriet Tubman on twenties.

So many of the freedoms we all enjoy today are a direct result of Tubman’s heroic efforts. But American money, and our national romance with it, is the root of so many of our national evils. Too often America attempts to atone for racism through style and symbol rather than substance. We don’t need America to put Black women on its money. We need America to put its money on Black women.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com